Ronnie Biggs dies at 84; British criminal helped pull 1963’s ‘Great Train Robbery’

LONDON — Ronnie Biggs, one of the most famous criminals in British history, who helped commit the Great Train Robbery of 1963, broke out of prison, enjoyed a notoriously colorful life on the lam in Brazil and then gave himself up, in thoroughly British fashion, to a tabloid newspaper decades later, has died. He was 84.

Biggs died during the night, his official Twitter account said Wednesday morning; a woman at the nursing home where he was living, outside London, confirmed the news. He had been ill off and on for the last several years.

Biggs fulfilled a wish by going to his grave a free man, despite having been thrown back in jail after returning to England in 2001 and surrendering to authorities. In August 2009, the British government relented from its unyielding stance and released Biggs from custody, concluding that — at age 79 and nearly incapacitated in his hospital bed — he no longer posed a threat to society.

Biggs joked at his release that he would try to last until Christmas “to spite those who want me dead.” He lived four more years. By coincidence, he died hours before the BBC prepared to broadcast a new two-part dramatization of the Great Train Robbery on Wednesday and Thursday.

Biggs’ last public appearance came in March, at the funeral of Bruce Reynolds, the robbery’s mastermind. Frail, in a wheelchair, but still spirited, Biggs was caught on camera flashing an obscene gesture at a photographer.

His death brought to a close a long-running saga that has fascinated and repelled this country for nearly half a century, sparking heated debate over the competing demands of justice and mercy and whether Biggs was an unrepentant felon who was party to a violent crime or merely a lovable rogue who loved to party.

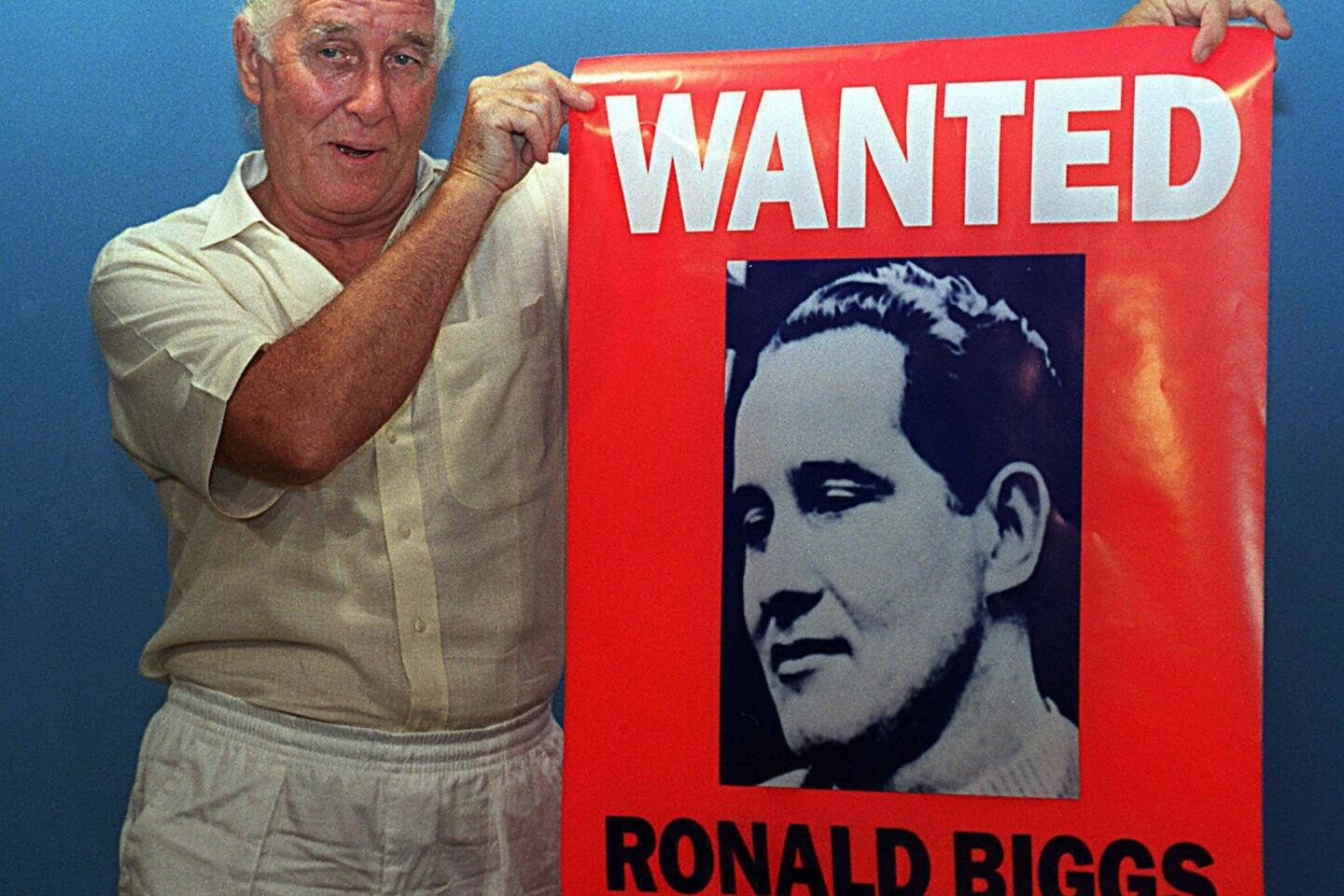

He certainly saw himself as the latter, cultivating an image as a catch-me-if-you-can figure who lived a playboy’s life on the beaches of Rio de Janeiro, merrily thumbing his nose at the authorities across the Atlantic while marketing himself as a tourist attraction to visitors he’d regale with stories — for a fee.

But Biggs also gave ammunition to his critics with statements like the one he made in a 1997 interview.

“I don’t regret the fact that I was involved in the train robbery. As a matter of fact, I’m quite pleased with the idea I was involved, because it’s given me a little place in history,” Biggs said. “I’ve made a mark for myself.”

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

His role in the robbery was almost an afterthought. The heist’s mastermind, Reynolds, an antiques dealer who went by the nickname “Napoleon,” invited Biggs to join in late in the process of putting together a daring plan to ambush the Glasgow-to-London mail train.

By then, Ronald Arthur Biggs, who was born Aug. 8, 1929, in Surrey, south of London, was a carpenter looking for some easy money. On his 34th birthday, in 1963, Biggs and 14 other masked thieves forced the mail train to stop by turning a track signal to red, swarming aboard under cover of darkness.

They beat the driver senseless with an iron bar; the man never fully recovered from his head injuries. Then they made off with 120 mailbags stuffed with unmarked currency amounting to 2.6 million pounds — well in excess of $65 million today. Biggs’ share was a little less than 150,000 pounds.

The gang divvied up the loot in a farmhouse, which they paid some people to burn down afterward. But the arson did not go off as planned, leaving behind enough evidence for authorities to track them down.

For the British, caught in the grip of imperial decline, the robbery was a national sensation, the “crime of the century.”

Authorities arrested and convicted more than a dozen people, including Biggs, in connection with the heist. But most of the stolen money was never recovered.

Barely 15 months into his 30-year sentence at Wandsworth Prison in London, Biggs managed to escape in July 1965 by scaling a 30-foot wall with a rope ladder. He fled in a furniture van and eventually washed up in Australia, spending much of his share of the stolen cash along the way on plastic surgery to alter his appearance.

But Scotland Yard — in particular, a detective named Jack Slipper — kept up its pursuit of him, which forced Biggs to look for a new fugitive-friendly haven. He chose Latin America.

“There’s 100,000 Nazi war criminals hanging out there,” he said. “That’s the place to go.”

In 1974, Slipper, who was Sherlock Holmes to Biggs’ Professor Moriarty, was tipped off to the train robber’s whereabouts by a British newspaper. He flew to Brazil for the collar.

“Nice to see you again, Ronnie,” Slipper said after strolling into his elusive quarry’s hotel room in Rio.

But Biggs gave Slipper the slip. When it emerged that Biggs’ Brazilian girlfriend was pregnant with his child, Brazil refused to extradite him, leading to a famous photo of the thwarted Slipper returning to Britain with an empty seat next to him on his flight.

Safe from deportation, Biggs began living large, his brazenness as much a source of head-shaking admiration in his native land as of anger over his continued cheating of justice, especially after the train driver beaten in the robbery, Jack Mills, died without ever being able to return to his job.

To make money, Biggs traded on his biggest asset: his notoriety as a convict on the run (though “on the run” meant plenty of time lying on Copacabana Beach in a skimpy bathing suit).

He charged tourists for the privilege of meeting him. He sold T-shirts that boasted: “I went to Rio and met Ronnie Biggs — honest!” He promoted a burglar-alarm system with the slogan “Call the thief” and recorded the song “No One Is Innocent” with the punk group the Sex Pistols.

“I’ve got no shame whatsoever. When you’re hard up, man, and your back’s against the wall, you hustle,” he said. “That’s what I’ve done. I’ve become a good hustler, you know — a lousy thief but a good hustler.”

He was at the center of yet another imagination-defying episode when, in 1981, ex-British soldiers kidnapped Biggs and smuggled him to Barbados, apparently with the intention of turning him over to the British government. But Barbados police found Biggs aboard a drifting yacht and sent him back to Brazil.

In 1999, Biggs celebrated his 70th birthday with a party in Rio whose guest list included Reynolds, the former ringleader of the Great Train Robbery, who had spent 10 years in prison.

By then, however, ill health, if not the British authorities, was catching up to him. A series of strokes left Biggs barely able to walk.

In 2001, he announced that he wanted, at last, to go home to Britain, where his dream was “to walk into a Margate pub as an Englishman and buy a pint of bitter.” (Margate is a seaside town on England’s southeastern coast.) Less-charitable observers said it was more likely that Biggs, broke and in need of decent medical care, wanted to return to sponge off of the National Health Service.

Biggs gave himself up to the Sun, Britain’s biggest-selling tabloid, which chartered a private jet to fly him back home. He arrived May 7, 2001, wearing a cowboy hat and a Sun T-shirt.

“I’m coming back in style with my head held high,” Biggs told the tabloid. “I’m on my way and ready to finally face the music.”

He was arrested upon landing, then remanded to the high-security Belmarsh Prison in southeastern London to serve out the remaining 28 years and 9 months of his sentence.

Lawyers filed repeated appeals to spring him from jail. In truth, Biggs would spend much of the rest of his life in a hospital in eastern England rather than behind bars. The British government continued to reject his parole applications, ruling that he was “wholly unrepentant” over his crime.

Officials finally relented on “compassionate grounds” in 2009, at which point Biggs was unable to feed himself, ill with pneumonia and, according to his doctors, unlikely to recover. Still, the decision outraged many Britons who felt that Biggs had once again “cocked a snook” at justice.

The day before he turned 80, Biggs’ walking papers came through by fax, and the guards who monitored him were withdrawn.

“Ronnie Biggs is free ... to die,” the front-page headline of the Times of London declared.

But he vowed not to go just yet.

“I’ve got a bit of living to do yet. I might even surprise them all by lasting until Christmas — that would be fantastic. I’ll live on just to spite those who want me dead,” he told a newspaper.

Many years ago, Biggs said he deserved to be free.

Since his escape from Britain, “I’ve maintained an honest life. I’ve done nothing against the law. I fully believe I have wiped the slate clean,” he said. “If they say prison is to rehabilitate a person, then to my satisfaction, I am totally and completely rehabilitated.”

That, however, is a question that will no doubt live on.

Biggs is survived by his wife, Raimunda Rothen; their son, Michael; and two sons, Chris and Farley, from a previous marriage. Another son, Nicholas, died in a 1972 car crash, according to the Associated Press.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.