Conservation hopes live at San Diego’s Frozen Zoo

Less than one month after his death, Ranchipur, the 50-year-old Asian elephant, was entering the next stage of the San Diego Zoo’s circle of life.

Ranchipur’s new chapter was unfolding inside San Diego Zoo Global’s Beckman Center for Conservation Research, where cells from the 10,000-pound elephant were bound for a tank filled with liquid nitrogen and a future that we can’t even imagine yet.

The elephant was about to become a resident of the Frozen Zoo, where the end of life can be the beginning of a whole new journey.

“We told the keepers, ‘If it helps, a piece of him is living in the Frozen Zoo,’” senior researcher Marlys Houck said of the cells from the elderly elephant, who was euthanized at the zoo in August. “We don’t know what (the cells) will be used for in the future, but they are a source of DNA. So when we get them, we bank them. The time to bank is while the species is abundant. The pressure when it’s down to the last one is just so much.”

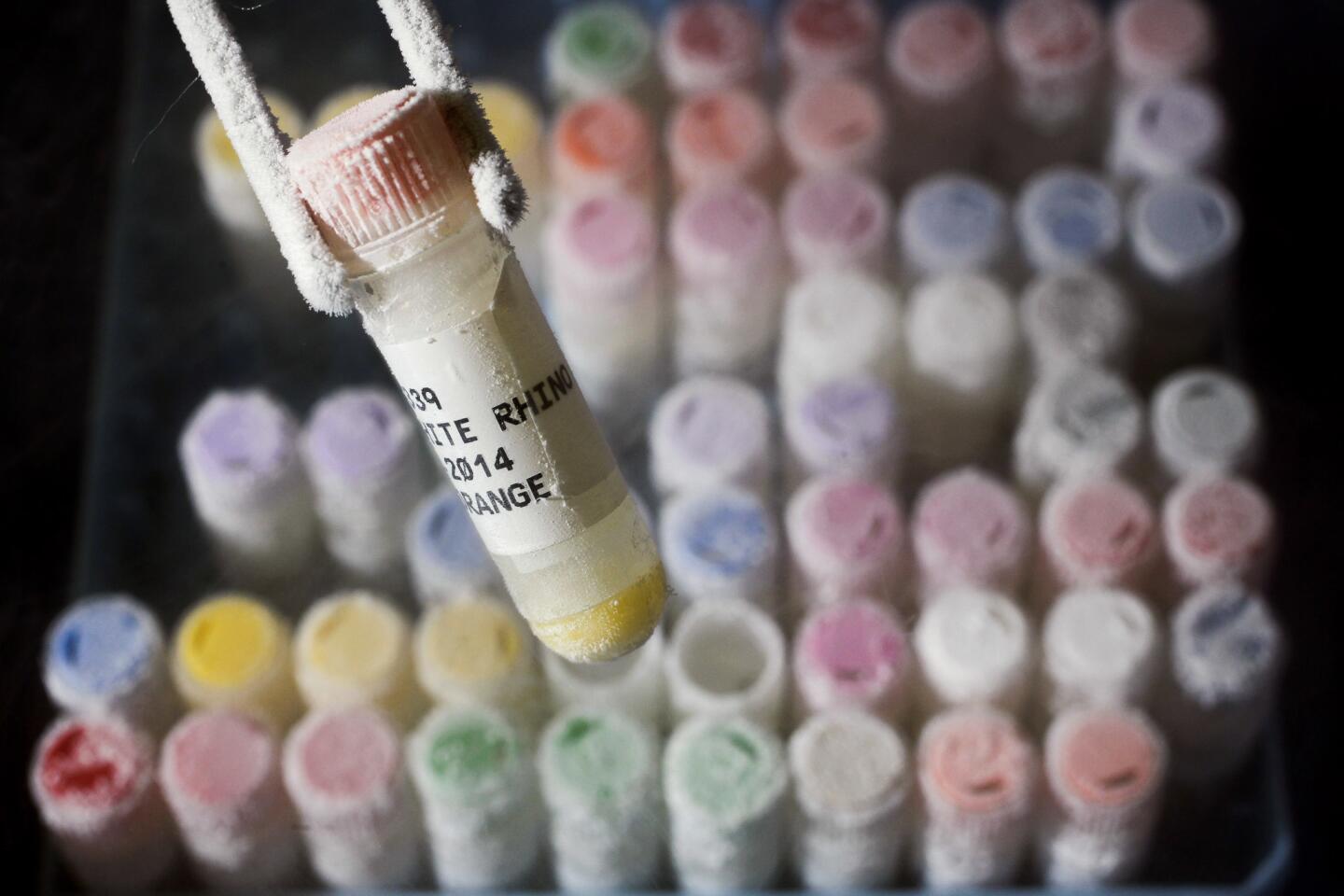

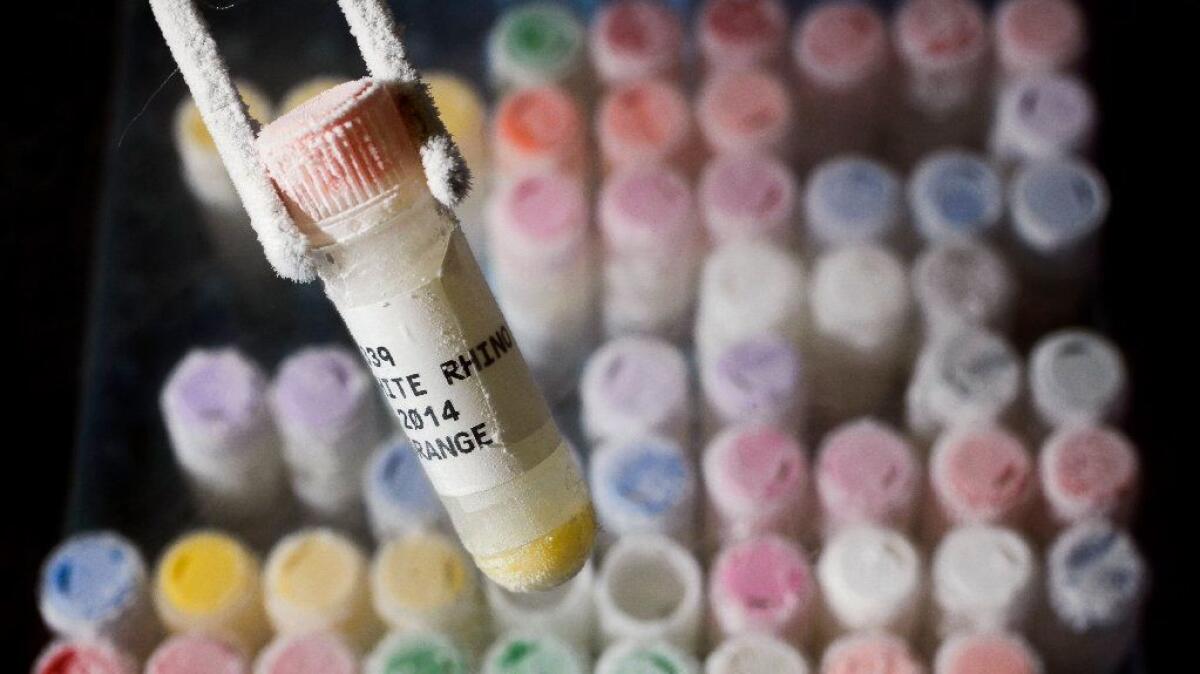

Located just up the road from the San Diego Zoo Safari Park near Escondido, the Frozen Zoo is home to more than 10,000 living cell cultures, sperm and other genetic materials representing nearly 1,000 species and subspecies.

Inside six tanks filled with liquid nitrogen kept at minus 320 degrees Fahrenheit are genetic materials from massive elephants, Oustalet’s chameleons and the last po’ouli, a bird native to Maui that went extinct a decade ago. A matching set of tanks (and their contents) is housed at a second undisclosed location, just in case something goes awry at the main site.

The samples in the genetic bank come from the Zoo and the Safari Park, as well as from other zoos and institutions all over the world. They are taken during routine health exams or after an animal has died. No animals are sacrificed for the sole purpose of populating the Frozen Zoo.

The materials have been used to inseminate Bai Yun, the zoo’s beloved giant panda, and to reproduce the endangered Chinese monal pheasant. The Frozen Zoo’s vast collection is a big contributor to the Genome 10K project, a worldwide effort to sequence the genomes of 10,000 species. It is also a key player in the fight to save the critically endangered northern white rhino from extinction.

Then there are the uses no one has discovered yet. Because unlike its icy collection, the Frozen Zoo is fluid. No one knows where it might be going next, including the people who know it better than anyone else.

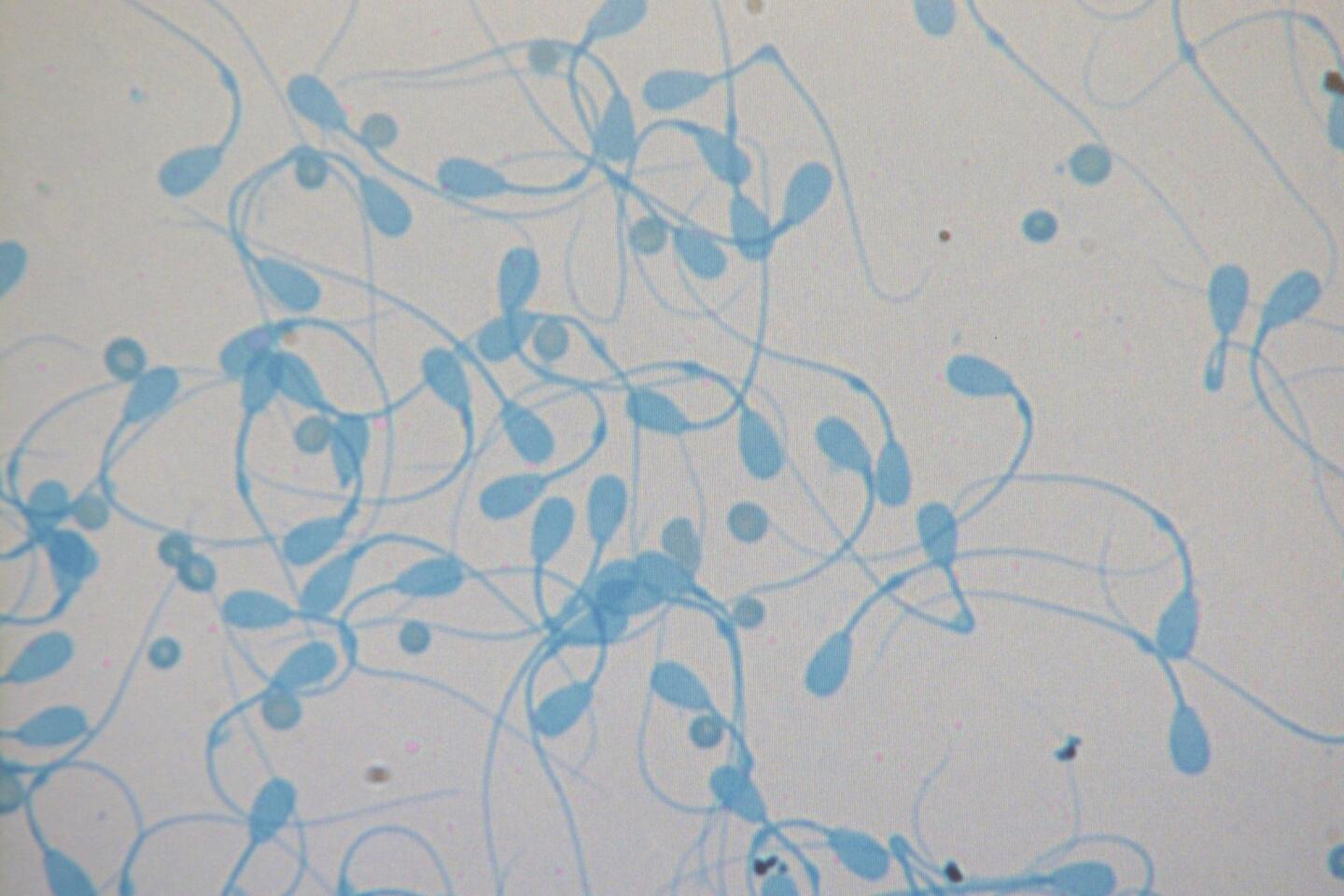

“Every day, we have less genetic diversity on the planet than we had yesterday,” said Barbara Durrant, San Diego Zoo Global’s Henshaw endowed director of reproductive physiology. “If I collect semen from a gorilla now, I may not have a plan, but we may need that sperm in the future. The idea is to capture what we have today and use it at the most appropriate time in the future.”

The Frozen Zoo was the brainchild of Dr. Kurt Benirschke, a UC San Diego pathologist and geneticist whose keen interest in human genetics led him to study reproductive issues in animals. In 1975, he and former zoo executive director Charles Bieler persuaded the board of trustees of the San Diego Zoo to establish the Center for Reproduction of Endangered Species, which would become the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research.

Bernirschke began collecting frozen cells and reproductive material in the 1970s. Finding a purpose for this genetic stash — and waiting for the technology that would make using it possible — would take awhile longer.

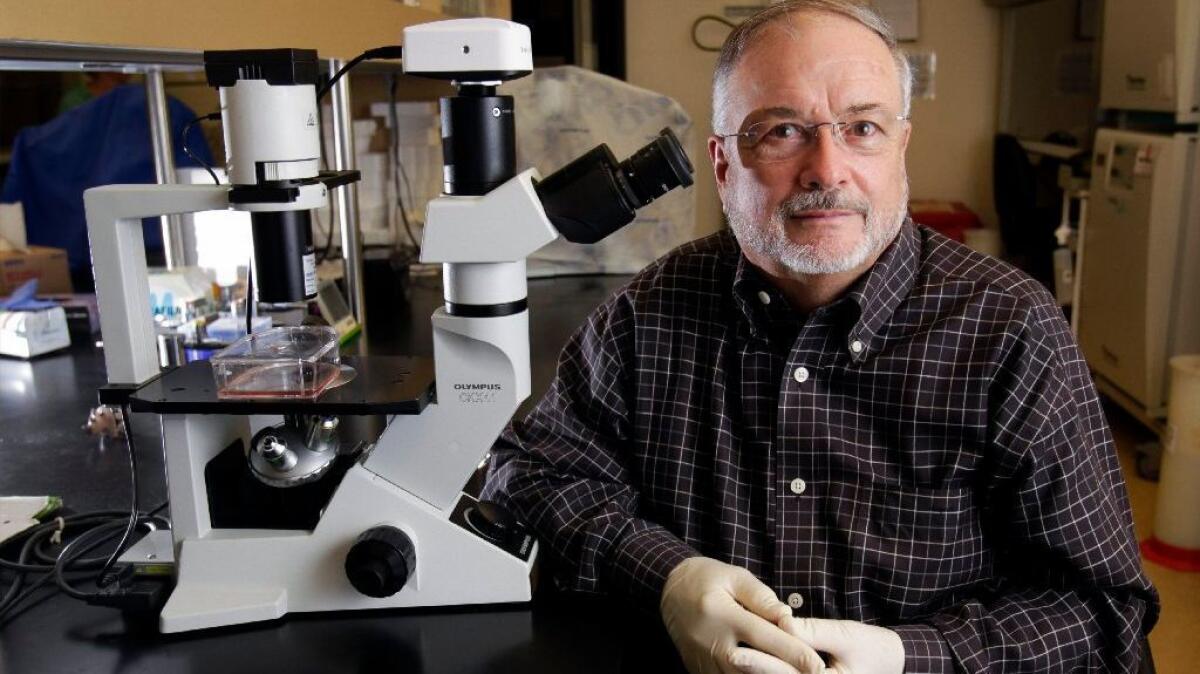

Around that time, Oliver Ryder was working on his doctorate in biology at UC San Diego and pondering the problem of endangered species. He was introduced to Bernirschke, who proceeded to change Ryder’s career plans, along with the rest of his life.

“I walked into his office, and I remember saying to him, ‘Is there anything a molecular biologist can do to save species?,’” said Ryder, now San Diego Zoo Global’s Kleberg endowed director of genetics. And he said, ‘Yes, but you will have to figure it out.’”

A few key scientific discoveries helped on that front. In 1996, scientists in Scotland cloned Dolly the sheep. It was the first time a mammal had been successfully cloned, a breakthrough that quickly expanded the horizons of what could be done with genetic materials.

Another key milestone came in 2006, when Japanese researcher Shinya Yamanaka discovered that mice skin cells could be reprogrammed into immature stem cells, the kind of master cells that can grow into different types of cells within the body.

Five years later, Ryder and his genetics team collaborated with Jeanne Loring at the Scripps Research Institute to generate these all-important stem cells from the frozen skin cells of the critically endangered northern white rhino and an endangered African drill monkey.

“We realized that the Frozen Zoo was possibly the world’s largest collection of stem cells,” Ryder said. “This collection is going to be useful for more things than we can possibly imagine.”

Just as the animals represented in the Frozen Zoo range from the exotic Przewalski’s horse to the ubiquitous domestic cat, the work being done by the genetics and reproductive teams is all over the scientific map.

Genetic studies have helped improve the care of animals by identifying reproductive issues in pandas. Amphibians are suddenly dying off at an alarming rate, and the Frozen Zoo’s large collection of hard-to-gather amphibian materials will help researchers find out why.

Sequencing the genome of Swazi, the matriarch of the San Diego Zoo Safari Park elephant herd, contributed to the Human Genome Project. And the cat testes and ovaries the facility regularly receives from the Feral Cat Coalition’s spay and neuter clinic have helped Durrant and her staff perfect the sperm and egg freezing techniques they have then used with cheetahs.

Other uses for the Frozen Zoo sound like the stuff of science fiction. In the early 2000s, cells from the Frozen Zoo were used to clone two endangered cattle species, a gaur and a banteng. The cloned gaur died of an infection within two days. The banteng, a male named Jahava, survived and went on display at the zoo in 2004. He was euthanized seven years later after breaking a leg.

If cloning represents the outer limits of what the Frozen Zoo could do to save endangered species from extinction, the slow and steady work happening at the Safari Park’s Nikita Kahn Rhino Rescue Center is no less groundbreaking.

The plan is for the center’s six female southern white rhinos to act as surrogates for a hybrid rhino. The hybrid would be created from frozen sperm from the nearly extinct northern white rhino and eggs from the southern white, whose conservation status is the less-scary “near threatened.”

In the next phase, which could be 10 to 15 years away, Durrant and her team hope to use Frozen Zoo cell lines from Nola, the much-loved northern white rhino who died at the Safari Park last year, to help create a northern white embryo that would be carried to term by a southern white surrogate. The ultimate goal is to have a population of northern white rhinos living in the wild. Habitat loss and poaching have reduced the current northern white population to three animals living on a preserve in Kenya.

Whether it is through cloning or surrogacy, when you talk about creating new animals in a lab, animal-rights activists and other skeptics wonder if it is something humans should be doing. What is the point of keeping a species alive if the animals have to live in zoos? Why spend so much time and so many resources on one subspecies?

The scientists say humans have an obligation to intervene when the extinction is a result of climate change, poaching and other man-made causes. We broke it, so we need to fix it.

“The phrase that comes up a lot in these debates is the idea that we are ‘playing God.’,” said Andy Lamey, assistant teaching professor of philosophy at UC San Diego, where he has lectured about the ethics of cloning extinct animals such as the woolly mammoth. “A certain amount of extinction is normal, but that is based on how it occurs.

“Historically, most extinctions were not due to thoughtlessness on the part of our species. But when we talk about extinction today, we are overwhelmingly talking about people encroaching on an animal’s area. And even if you spend a lot of time trying to save one subspecies, the lessons you learn there could save a lot of species.”

The samples in those liquid nitrogen tanks are small enough to fit in your hand, but the lessons being learned at the Frozen Zoo could change the future for animals of many stripes. Those samples are small enough to fit in your hand, but their impact could be bigger than our human minds can imagine.

So when something happens with one of the Frozen Zoo’s liquid nitrogen tanks — a change in the nitrogen level, a power surge, a power failure — an alarm goes off and researcher Houck gets an alert text. The minutes she spends waiting for security to report on the source of the problem can be excruciating. Because if something happened to the Frozen Zoo, the flood of loss would be felt far beyond this one small room.

“It can definitely keep you awake at night, but this is extremely rewarding,” Houck said. “This is going to outlive all of us. What we are doing today will be here long after we’re all gone.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.