‘Homies’ are where his art is

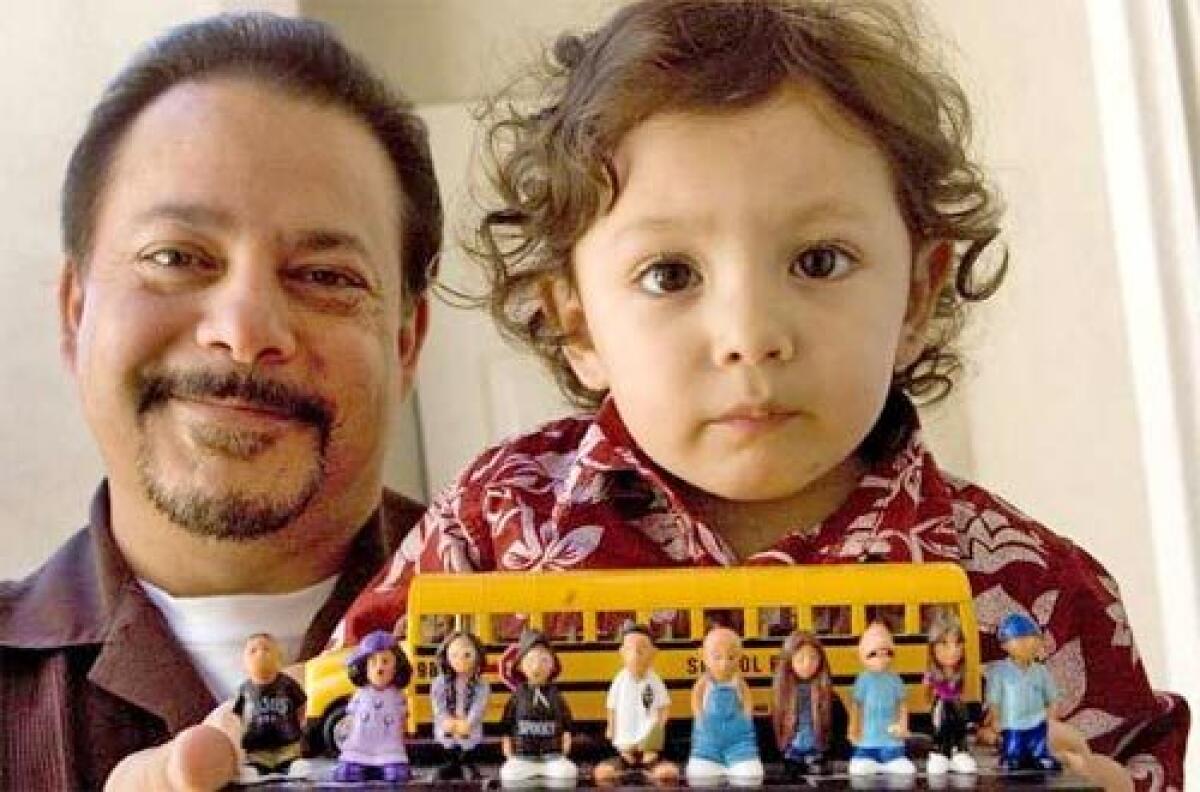

HERCULES, CALIF. — Ten years ago, David Gonzales created a hit with “The Homies,” 2-inch plastic figurines depicting characters from the barrio, complete with bandannas and baggy pants. Inspired by the homeboys he grew up with, they were sold, quarter by quarter, in gum ball machines in mostly Latino neighborhoods.

Gonzales was lambasted by police and prosecutors, who said the impish images exploited gang life for profit. Naturally, they then sold better than ever: more than 120 million to date.

The 47-year-old Gonzales, now a father of three children in college, lives in an elegant two-story Spanish-style house overlooking San Francisco Bay, just down the road from the flinty central Richmond neighborhood where he grew up.

“I call this house ‘the house that the Homies built,’ ” he said.

Gonzales has been featured in national magazines, including Rolling Stone, and rubbed shoulders with celebrities. His characters have adorned back-to-school folders, lunchboxes, breath mints and beach towels. The Pasadena Museum of California Art is hosting an exhibit on his Homies, and Nintendo will soon release a Homies video game.

Yet there has been a gnawing feeling of unfulfilled goals and unmet expectations. He wanted to hit the big time with an animated TV show -- something that would really leave his imprint. Oil paintings by Gonzales, often with religious themes, hang on the walls of his home -- a reminder that the artist created the toy maker, not the other way around.

He felt harried by a sense that time was slipping away, sounding curiously like someone stuck in his own plastic bubble. Sometimes, he bared his soul to a priest.

But not just any priest.

Gonzales, one of five boys in a family scraping by in a tough neighborhood, grew up intense, artistic and studious. He asked his parents to take him out of a Roman Catholic school and enroll him in a public school because the latter had an art program.

“I knew David was going to be an artist,” said his mother, Agnes.

His brother Robert, younger by a year, hung out with a rougher crowd. He got into fights, burglarized homes with his friends and landed in jail. He dropped out of high school.

The brothers were close, but their paths kept diverging. David enrolled at California College of the Arts in Oakland. He drew a comic strip for Lowrider magazine with characters familiar -- for better or worse -- to just about anyone growing up in Mexican American barrios. Robert moved to Nevada to work in the Job Corps.

One day in 1980, David got an urgent call from a hospital in Reno.

Robert and some friends had scuffled with a group of young men on the side of a desert road. Someone had hopped into a car and gunned it in Robert’s direction, pinning him between two cars. His right leg had to be amputated below the knee.

When David and their mother reached the hospital, a priest told her that Robert must have been pulled from the grave by a guardian angel. The priest also remarked that Robert was highly spiritual, a comment that surprised his family.

David went back to college and Robert returned to his parents in Richmond. But even in a wheelchair he was rebellious, blowing insurance money on a lowrider and partying harder than ever. He moved out but soon felt lonely, isolated and miserable. He drank a lot.

One day, Robert returned to Richmond and found David in their parents’ garage. If anyone could understand him, Robert figured, it would be David.

Robert wept. He told his brother he wanted to come back home. But he felt ashamed. What Robert really seemed to crave, David thought, was forgiveness -- penance.

“The prodigal son spends his riches and comes home. He rejects his parents’ love and direction,” David said, recalling what he learned in church and Catholic school. “A lot of people screw up in their lives and leave, and their parents slam the door in their face when they come back.”

But David knew that would not happen to Robert, even if his brother had doubts. “Just speak to Mom and Dad,” he told him. “They’ll understand.”

So Robert spoke to them.And they welcomed him back.

In the ensuing years, David made money designing T-shirts and selling them at flea markets and liquor stores. One of his first bestsellers featured Barturo, a barrio version of Bart Simpson who asked: “¿Qué pasa, dude?” Another successful shirt featured the Virgin of Guadalupe.

He took a job as an artist with the Postal Service in Oakland to support his wife and children. He painted a huge mural titled “Journey of a Letter” in a post office lobby in Fremont but eventually quit so he could pursue the T-shirt business full time, refining his barrio creations.

Then a manufacturer called him about making plastic figurines of his comic strip characters.

Meanwhile, after his garage chat with David, Robert patched up things with his parents, enrolled in vocational school, graduated with honors and took a job at a savings and loan. But, as David would feel years later, Robert sensed something was missing in his life. There had to be, he decided, a reason he survived the attack. One day, he called his parents into the living room and announced that, at age 24, he wanted to become a priest.

“He was the last person I expected to be a priest,” his mother said. “When you think of a priest, you think quiet and studious. Robert was so rebellious.”

In 1989, the year the Homies figurines made their debut, Robert took his religious vows and a new name, Masseo, after one of St. Francis’ followers. When Robert was ordained as a Franciscan priest seven years later, David read a speech.

“Knowing Father Masseo . . . I’m sure he’ll be dealing with a lot of problems facing young people, such as drugs, gangs and teen pregnancy,” David said. “He’ll be an important part of a lot of baptisms, first communions and confirmations. Those will be his children.”

Soon enough, David would need Masseo for his own talk-in-the garage moment.

He was making lots of money. By most accounts, Homies were the best-selling character brand in vending-machine history. But police and prosecutor complaints were wearing on him. Many stores stopped selling Homies, and lots of people thought he was glorifying gangbangers and profiting from it.

The Homies, with names such as Chuco, Joker and Poco Loco, were just his humorous tribute to a subculture of Latino life, he said. “I’m not going to stop gangs, and I didn’t create them,” David said, sounding slightly exasperated. “They exist. Just like they exist in the regular Hispanic community, they exist in the Homie world.”

David fired off a frustrated e-mail to his brother, saying that he was thinking of going back to the Postal Service. He found it hard, David said, to accept that “God blessed me with all this . . . artistic talent for that job in life.”

“God didn’t give you this talent for nothing,” his brother replied.

The priest also reminded him that even a toy maker had a larger responsibility. Not every Homie had to be vato, a dude in the barrio.

So David kept at it. He created El Paletero (the ice cream vendor), who works to bring his grandchildren from Mexico. And Officer Placa, a rotund, doughnut-loving cop who “worked the barrio for about 20 years and knows all the Homies by name.”

Robert suggested he create a figurine of a homeboy in a wheelchair -- a common sight in gang-afflicted neighborhoods. Willy G. became the most popular Homie ever. Soon, David got calls from the Special Olympics and from people who coached youngsters with disabilities.

He also created a homeless man, a young student and an activist. But no character would have a life of its own, and bind the two brothers, so much as El Padrecito (“the little father”) -- a Franciscan priest with robes, sandals and stylish sunglasses who “acts like a second father to many of the Homies” and looks a bit like Robert.

The Padrecito turned out to be more than just a figurine. Masseo adopted him as his personal logo and found that the Homie helped him reach young people in need. Robert created El Padrecito’s Online Church, where he fields questions, offers upbeat advice, counsels the troubled and sometimes delivers a religious message in rap.

“My life would probably be a lot more boring without the Homies,” the priest said.

Robert talks optimistically about his dream of opening a monastery in the town of Guadalupe and reaching ever more people through the cyber-church.

To help Robert along, David sold him the rights to El Padrecito for $1 and gave him permission to use all of the Homies in his religious efforts. And last year David created Santos, a line of figurines of saints and religious figures, such as Pope John Paul II. David also donated $20,000 to his brother’s growing cyber-church.

Last year, a young woman from Houston e-mailed El Padrecito to say she was about to earn her college degree. She wanted to thank the father for helping her cope with the execution of a family member on death row years before.

“Crazy as it sounds,” she wrote, “if I hadn’t written to you so long ago, my life may have turned out differently and I could have been just another statistic, just another face on the welfare line.”

Could the priest have reached out to the young woman without El Padrecito? Probably, but the Homies certainly made it easier, Robert said. And the priest brought the artist a measure of redemption as well. “He helped the Homie family stay on the right path,” David said. “It was reaffirming for me, and it let me know that I had not gone too bad.”

And who would have ever expected that from the creator of Chuco, Joker and Poco Loco?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.