A life of honor, one day at a time

It happened again at a Taco Bell. The old way of thinking, the criminal voice, wouldn’t shut up inside the head of Ken Layton.

Yeah, take out that punk kid, beat the crap out of him, show that pimply faced idiot he ain’t nothin’ and you’re still Folsom Kenny Layton.

He was standing in line at the fast-food joint, behind an overwhelmed woman with an unruly child. She was complaining about her order, and the kid behind the counter kept putting her down. “He was rude,” Layton said. “Sarcastic.”

Layton, 64, had been out of prison for 20 years. And yet the old thinking was back, a twisted moral code that he wrote in childhood, refined over decades behind bars and enforced throughout early adulthood, no matter who got hurt.

These are the words Layton had planned to say, before the old thinking took over: “Hey, kid, you’re in customer service and you’re being rude to a customer. If you keep that up, you’re not going to make it.” Firm. Wise. Helpful. But criminal thinking swept in, rewrote the script and instead he said, “You’re a punk, and if you don’t like it, I’ll meet you in the parking lot.”

Folsom Kenny got his taco order and tossed the food in the trash before pounding open the door.

His wife, Carlie, hungry for tacos but seeing no fast-food bag, watched him from their car. “He kind of tilted his head and put on a gangster walk,” she said. He didn’t smile and wave like he always did; just wordlessly got in, slammed the car door and cut off a driver as he peeled out of the parking lot.

For many ex-cons, this is the kind of moment that can precede a crime and, ultimately, a return to prison. A 2002 Justice Department study that tracked prisoners released in 15 states found two-thirds of them were rearrested within three years for a felony or serious misdemeanor. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, in a 2006 report, tracked inmates for two years after their release and found a recidivism rate of 38% after one year. After two years, 51% of released California prisoners were back behind bars.

Layton knows why: prison thinking, convict thinking, criminal thinking.

In his case, it was still there, decades after his last crime. But as he drove down the street with his wife, Layton adjusted. Within a few blocks, he’d found a way to stifle Folsom Kenny.

Layton’s ability to defuse his anger is a rare skill for an ex-con, but it doesn’t have to be. Experts think helping criminals understand how their thought processes are connected to the crimes they commit is more than just a touchy-feely exercise. It can reduce recidivism.

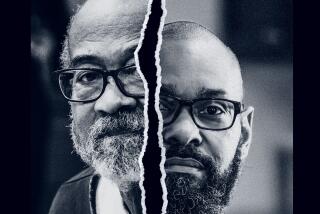

Layton’s struggle, chronicled in his own contemporaneous writings and later recollections, is a case study in how the criminal mind works -- and how with guidance, practice and will it can change.

Layton’s story, like the stories of many criminals, begins with a litany of gut-wrenching stuff from a deplorable childhood -- raped by his brother, sexually molested and humiliated by his mother, beatings, fights, running away from home. By seventh grade he was sniffing glue, by eighth grade he was stealing cars, and by the age of 14 he was locked up in the juvenile detention center in East Los Angeles.

“I always knew I was a coward at heart,” he said, and recalled what he believed to be the core of his criminal thinking:

Ain’t nobody going to do that to me again. You think you’re going to hurt me. Hah! I’m going to show you something. I’m going to show you some violence you don’t want to see. Ain’t nobody going to do that again.

It was, he said, a front that concealed other thoughts:

I’m scared. All the time. I talk my way out of fights. I run from them if nobody’s looking. If somebody starts peepin’ my hold card, I gotta get them away. They gotta know this other guy, this tough guy, not the coward I really am. I know I’m nothin’. Can’t let anyone else see it. I’ve got to learn how to be tough.

Until he reached juvenile detention, he said, he had some vague sense of right and wrong. In fact, he kept a tally, a written list of what he did that was wrong, what he was ashamed of: stealing from his mother, running from a fight.

In juvenile detention, he crumpled the tally, threw it out and never kept a list again. By then, he said, he had decided he was going to be a criminal. His moral code flipped from worrying about right and wrong to consciously and consistently choosing wrong.

[Expletive] that list. I’m just going to do the wrong thing every time. Then I don’t have to keep no list. I’ll make a new set of rules. I’ll be the baddest convict the Laytons ever knew. The whole world is sick and nuts. They want to try to get over on me. Uh uh. I’m gonna get over on them.

Do unto others before they do unto you -- that was his new rule.

When he was released from detention, he continued stealing and fighting. He was about 20 when he switched from knives to guns. He hooked up with a robbery ring and worked his way up from convenience stores to supermarkets and pharmacies. His robberies landed him in San Quentin, Soledad and Folsom prisons for all but a few months of his adult life.

In one robbery, his getaway driver freaked and was gone by the time Layton ran from a supermarket. So he dashed into a house whose owner tried to stop him. He shot and wounded the homeowner, and as the guy fell his wife, seeing her bleeding husband, collapsed with what Layton later found out was a stroke.

He remembers blaming the victim.

What the hell is he doing, running after me. Can’t he see I’m the one with the gun? What’s wrong with him? He’s getting in my way. Don’t he know who I am? BANG.

His final crime was a drug store robbery in Oregon. His car broke down during his escape. He hitched a ride with a couple of kids who, after they dropped him at a bus station, called the police to report that he had a gun and appeared nervous.

The cops were waiting at the bus station in San Francisco when Layton got off the Greyhound. None of it wiped the scowl off his face.

But he was stifling a sigh of relief, he said. I’m goin’ home, the home I know, where I know the rules and what to do and how to do it.

He rode through the gates of the Oregon State Penitentiary, believing it safer than any prison he had known. This is gonna be a breeze.I’m in heaven. Dope and handball. They sleep in the [expletive] yard! You could never sleep in the yard at Folsom.

By the time he arrived at the Oregon prison in 1977, Layton was 34, 6 feet 2, a tattooed and muscled 200-pounder who wore shades and a navy stocking cap pulled to his eyebrows. Larry Roach, then administrative assistant to the warden, said Layton made the top three on his “most dangerous inmate” list. “He was the fiercest man I had ever seen,” Roach said.

Roach started talking to Layton, debating really, about the values of a law-abiding life versus a convict life. Layton argued the virtues of the convict code, the freedom of living without regard to rules, the integrity of not snitching, of loyalty to fellow convicts who also kept the code.

Roach countered that the freedom to come and go is worth the price of following society’s rules. “At the end of the day, you go to bed when someone tells you to. You wake up when you’re told,” he recalled saying. “I go home. I can have a beer, have sex with my wife. Who’s free?”

It was an argument that went nowhere for years. Roach still has a treatise Layton wrote in 1980. In it, he compared two classes of prisoner: the lowly inmate, living without a moral compass, and the exalted convict, living according to a strict code.

“Consider the inmate. He is a prisoner who cooperates with prison officials, for personal gain will cooperate with any authority. He is a coward. In prison, he will snitch on, step on and generally disrespect [other prisoners] at every opportunity, as long as protection is sure and swift. . . .

“The title ‘convict’ is earned. The convict, by his own choice, lives outside society’s social structure. He has chosen to adhere to the social structure commonly known as the ‘convict code.’ It’s never been written up. It’s a code of survival as an independent person. He knows with cool certainty that no authority nor any man can break him. The convict is, and will be, the top of the line in his world, as long as he adheres to his chosen code of ethics. He will, till his last breath, be a man of integrity, and in his heart, he will be free.”

Roach began to see the distorted integrity in Layton’s values. “He was studiously adherent to ‘the code.’ It’s not our code, but in their world it’s morality,” Roach said.

Layton thought he found backing for the code in philosophy and religious writings. He read Viktor Frankl, who wrote: “Everything can be taken from a man but . . . the last of the human freedoms -- to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” Layton took that to mean The Man couldn’t mess with the integrity of his convict code.

And when he read “A Course in Miracles,” a kind of New Age spiritual text, it too reinforced his criminal values.

Look at me. I’m the Special Son of God, don’t you know.

Then Layton got sick. He had systemic vasculitis, an inflammation of all the blood vessels in his body, a consequence of Hepatitis B infection. The inflammation was attacking all his of organs, and he was slipping away. Roach moved him to the Oregon Health & Science University Hospital in Portland.

The doctors there, using immunosuppressive drugs, restored his health. He was in shape to return to prison, but he had lost the strength and speed he had always counted on to keep safe. He said to Roach, “I can’t do this anymore.”

Roach asked him what he wanted, and both remember his response: “I want to be an honorable man, but I don’t know how.”

He was ripe for change. Roach helped him get admitted to the prison system’s correctional treatment program at Oregon State Hospital near the prison.

The director was Jack Bush.

“We teach people how to be objective observers of their own thoughts,” said Bush, who now consults with a similar treatment program in Vermont’s prisons.

On his first day of treatment, Feb. 28, 1985, Layton was asked to write down ways in which he had hurt people. It was a long list. And as he left the room, he caught a glimpse of himself in a mirror. He held eye contact with his reflection, recognizing who he was.

“I walked out of that little room. I seen the mirror. I said, ‘It’s you that does this [expletive]. It ain’t your mother; it ain’t your father. It’s you.’ When I saw the mirror, I realized I always blamed everybody else. But it was me, a nobody, who cut a swath through the world and didn’t give a [expletive] about anybody. I shot people; I humiliated people,” he said.

Layton was challenged to see the connections between his thoughts (I want that car) and his actions (car theft). Then, Bush said, the program challenges prisoners to examine the attitudes behind the thoughts, and to imagine alternative attitudes.

The goal, Bush said, is to turn an antisocial moral code into an acceptable moral code.

Prisoners are told to “pay attention to your thinking, pay attention to the connection between thinking and action,” Bush said.

And then they’re told to try an attitude adjustment. A criminal’s attitude, for example, could well be: No one respects me; therefore, I respect no one. Bush has seen that change to “ ‘I can respect them, even if they don’t respect me.’ That’s coming out of the mouths of serious felons,” Bush said.

Layton was ahead of the game before he got to the treatment program, Bush said, because he had already named his goal: “I want to be an honorable man.”

In everyday interactions at the program, he followed the rules. One was to report other inmates in the program if he saw them breaking the rules. “When I was in the program, reporting a crime meant that if I seen a fellow patient doing something wrong, I was supposed to take it to group,” he said. “But when I was a convict, the rule was you don’t tell.”

Once, in a walk around the grounds outside the program, another patient talked to a woman through a window in one of the female units -- a rule violation. “I said, ‘Man, I’m going to have to take this to group.’ And I did. It was one of the hardest things I ever done. It was breaking a lifelong code.”

I ain’t no snitch fought mightily with I am a responsible citizen, and the latter won out.

He kept journals during the three years of his treatment. He kept writing down his thoughts for a few years after his release in 1988. And when Bush moved to Vermont, Layton continued to write to him, and later e-mail him, especially when his thoughts started slipping dangerously close to criminal thinking.

Soon after he got out he went to a Wal-Mart, and a clerk gave him $10 too much in change. He returned it.

Practice, practice. I’m a citizen.

The process had taken hold.

He met Carlie at a Narcotics Anonymous meeting. She was the clean and sober single mother of a 5-year-old, and he was a clean and sober ex-con. They played softball on the same team, went out for coffee, played golf and took short trips with her son, Skip. Within a year they were married, and Layton jumped at the chance to be a stepparent. “God sent me Skip, and I lightened the load for Carlie,” he said. “I had to be an example for him, and it built my self-esteem.”

Carlie sees her husband’s criminal past as a chapter written by a man she has never known. “He always felt safe to me,” she said. “He has this calmness about him.”

Layton appears able to recreate how he thought for the first 40 years of his life and compare it with what goes on within his gray matter today. Like an alcoholic or an addict who doesn’t drink or shoot up, a criminal who doesn’t commit crimes faces a one-day-at-a-time challenge with no letup.

A cornerstone of the treatment program Layton went through is that, regardless of individual facts of terrible childhoods and despicable circumstances, there are no excuses for breaking the law.

When the stress of work -- he counsels juvenile offenders -- gets heavy, or his boss gets too demanding, he’s in danger of falling back, he said. That’s what triggered the Taco Bell outburst, and shortly afterward he talked with his wife, with his boss, to ease the stress.

He owns his own home, drives a decent car, has a new motorcycle and has paid taxes long enough to collect Social Security. (He prefers not to reveal his present location to prevent any grief from people from his past.)

How can this possibly be me after the first 40 years of my life?

At a seafood restaurant, the three old friends, Layton, Roach and Bush -- law-abiding citizens all -- gathered for dinner. Everyone except Layton studied the menu and made standard, middle-class small talk. They discussed the entree they might order, talked about dishes they’d eaten in other restaurants in other cities, and appeared in no hurry for the food to arrive.

Layton knows that he never will be quite like them, so easy with life.

He still wages internal mental bouts against criminal thoughts. “If I see an armored car and think about robbing it, I look away,” he said. “I’ve planned robberies in my head, but I didn’t do them.

“I still feel like I’m falling short, but I want to be the best person I can be.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.