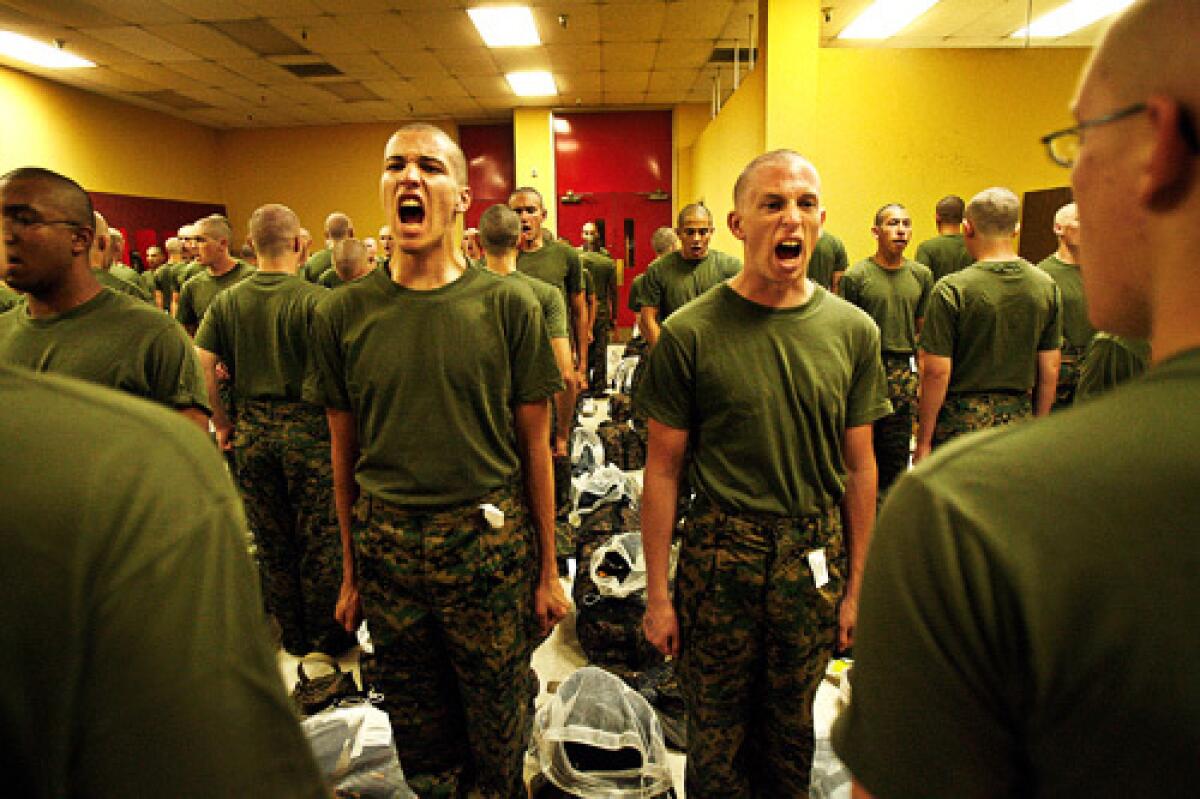

About to learn the drill at Marine boot camp

It was nearly 3 a.m. on a Monday when three weary teenagers arrived at the Marine Corps recruiting station in the Santa Clarita Valley. There to meet them was the station’s chief recruiter, Staff Sgt. Juan Diazdumeng, an energetic and enthusiastic presence, even in the middle of the night.

Daniel Motamedi, 17 years old and just 10 days past his high school graduation, rubbed his head and yawned. It was one of the most important days of his young life, and he seemed half-awake.

Daniel’s best friends, Daryl Crookston and Steven Dellinger, both 18, were yawning, too. The three had spent the previous week squeezing in the last pleasures of civilian life before shipping out to boot camp that morning. Going to bed on time was not among them.

Now, in the darkened shopping center where the recruiting station occupied a cramped corner, they filed in with parents and a dozen other recruits to hear Diazdumeng describe the next 13 weeks of their lives.

While still in high school, the friends had enlisted under the Marines’ buddy program, which guaranteed they would train in the same platoon throughout boot camp. In July, a Times article recounted the friends’ decisions to enlist and the trauma that had ensued in their homes. Now, their eager anticipation was about to run into reality.

Diazdumeng rattled off a compendium of boot camp horrors: Black Friday, four days hence, when the recruits are assigned drill sergeants and platoons. Hell Week, the third week, crammed with debilitating tests of stamina. The Crucible, the eighth week, a punishing three-day sojourn in the mountains of Camp Pendleton.

His voice softened as he offered final advice: “Listen to the drill instructors. Do everything they tell you. Do not ask questions. They are telling you to do certain things for a reason, OK? And have a great time. Boot camp is so much fun.”

It would be one of the last times over the next three months that a Marine in authority would speak to the three recruits in a calm, nurturing, reassuring tone. In just a few hours, they would be confronted by hyper-aggressive drill sergeants whose piercing screams would begin a process of stripping suburban teenagers of their civilian psyches, their blasé attitudes, their very identities.

“Questions? Moms? Dads?” Diazdumeng asked.

The friends’ parents initially opposed their sons’ enlistments in a time of war, but now supported their decisions to serve. Daniel’s mother, Yasmin Motamedi, a Los Angeles police detective, asked: “How long do they give them to learn how to make their beds?”

Diazdumeng smiled. “Oh, they’ll learn quick. Everything they do, they will get a class. Everything is speed and intensity down there.”

The three teens shrugged; they fully expected to be pressured and hectored. They were willing to endure the worst deprivations of boot camp for the end reward: wearing the Marine Corps uniform.

They were more than a little afraid, they admitted, but they felt prepared. Daniel hugged his parents goodbye as his mother choked back tears. Steven embraced his father, Jim Dellinger. Daryl had already said an emotional goodbye to his parents at home.

“At least my mom didn’t go waterworks on me,” Daniel said. She didn’t burst into tears until he had left.

Diazdumeng drove a van full of recruits from Santa Clarita to the Military Entrance Processing Station on Rodeo Road in Los Angeles. There, just after dawn, the sergeant walked them to the receiving area. An entry sign read: “Where the Stars Shine.”

Diazdumeng hugged each one and whispered encouragement. “Hey, you’ll do great,” he said. As the recruits reached the door, he yelled out: “I love you guys!”

The intake officer, a thin, intense woman carrying a clipboard, sang out in a saccharine tone: “Oh, isn’t that sweet! He loves you!”

Then her voice hardened: “Take everything out of your pockets! Now! Take off your belts!” They would be searched for drugs and other contraband.

The friends fumbled through their pockets and clawed at their belts. A Marine shouted out names. One of the teens answered: “Here!”

The Marine shouted back: “Here, what?”

“Here, sir!”

The processing center -- the largest of 65 such stations in the country -- was like a vast bus station filled with confused, sleepy teenagers. Recruits wandered from room to room, following color-coded footprints painted on the floors.

Future soldiers, Marines, airmen and sailors were being processed, tested, quizzed and shipped out. Most looked frightened and forlorn. A few adopted tough, stoic poses that fooled no one.

The three friends were given medical exams and blood tests. They filled out reams of paperwork. Daniel was so sleepy that he wrote “high school” in the space for the type of military job he preferred. Sheepishly, he asked for another form.

Daryl underwent a tattoo check for a small symbol he had recently burned onto his shoulder. He passed; the Marines do not permit tattoos that feature profanity, gang affiliations, racial slurs or pornography.

Marine recruits must be high school graduates with no criminal records, with certain waivers for home schooling, GEDs or misdemeanor convictions. Ninety-eight percent of Marines graduated from high school, according to the Corps.

The three boys easily met all conditions. They passed their drug screens, too. While they waited in a hallway, a Marine sergeant gave an impromptu lesson. He taught them how to stand at attention: feet at a 45-degree angle, thumbs and forefingers pressed together against trouser seams, head up, eyes straight ahead. They learned how to salute: palms flat and at a sharp angle to their brows.

The sergeant explained that drill instructors are highly sensitive to rank and position: They are to be called “sir” at all times. “Address them in a very loud tone,” the sergeant said. “It’s a sign of self-confidence.”

They would all be addressed as “Recruit,” he said, and they should get used to it.

The sergeant had the recruits practice making requests of a drill instructor.

Daryl tried: “Does this recruit have permission to go to the restroom?”

The sergeant shook his head. The restroom is “the head,” he said.

“And what else did he do wrong?” he asked the recruits. “He was wobbly. He wasn’t at the position of attention.”

Daryl stiffened and tried again: “Recruit Crookston requests permission to make a head call, sir.”

The sergeant beamed. “There you go,” he said. If permission were granted, he told Daryl, he should run full speed to the head -- and back.

The friends were taken to a conference room for a formal swearing in. An Army recruit remarked that the U.S. Army logo on the wall looked much cooler than the Marine logo.

“I’m afraid I’ll have to disagree with you there,” Daryl told the boy, staring at him over his shoulder.

The boy stared back and challenged Daryl to a fight: “You want to go disappear with me after this?”

“Yeah,” Daryl replied.

There was no chance of any fight, but Daniel and Steven liked the way Daryl defended the Marines, and slapped his back afterward.

The center’s commander, a Marine major, gave a long motivational talk, stressing educational opportunities and pay -- $1,500 a month for most recruits -- that with increases in rank would accumulate to $100,000 over four years in the unlikely event they saved every penny.

The major explained what Semper Fidelis meant (always faithful), as if the three teens didn’t know. He said they did not have to recite “so help me God” at the end of the oath. Everyone recited the phrase anyway.

Over the next few hours, the three friends from Santa Clarita did what members of the military have done for generations: They hurried up and waited.

At last, a bus arrived at midafternoon to take 41 Marine recruits to San Diego. The driver, a retired Army veteran, offered advice and played a movie, “Jarhead,” with its wrenching scenes of recruit abuse and degradation. The recruits argued later over how much of the film, if any of it, reflected reality.

The driver warned the recruits, just before reaching the Marine depot at dusk, that a drill instructor would soon rush aboard and “go crazy.”

“Look straight ahead. Do not be looking out the window,” he said. “Don’t give him an excuse to [mess] with you.”

Despite the warning, the recruits were startled when a drill instructor abruptly leaped aboard and screamed. He was a tall, angular sergeant. Spittle sprayed from his lips. The recruits froze.

“Sit up straight!” the sergeant screamed. “Get your eyeballs on me! You are now a recruit at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego. Starting out, the only words that come out of your mouth are “yes, sir,” “no, sir,” and “aye, aye, sir.” Do you understand that?”

The recruits bolted upright. “Yes, sir!” they hollered.

“You are going to grab everything you brought with you and you are going to get off my bus! Do you understand that?”

“Yes, sir!”

“Get off my bus!”

Lurching and stumbling, the recruits stampeded into the aisles and out the narrow front door. They followed orders to stand in yellow footprints painted on the concrete -- “my deck,” the drill instructor called it.

The footprints forced the recruits to stand so closely together that they appeared to form a single mass of flesh, not a collection of frightened teenagers. Even now, seconds into boot camp, the Corps was instilling its primal message: Marines are not individuals, but a brotherhood.

The process was designed to break them down as civilians and build them up as warriors. It was disorienting, and deliberately so; they would be kept up all that night and the following day.

The next few hours were a blur: Learning how to stand at attention, how to take orders, how to scream so loud their throats burned. They were warned not to even think about sneaking in drugs, alcohol, pornography or any reading material other than religious works. They were told they would be jailed if they tried to flee the depot.

A series of drill sergeants, in what amounted to an assembly line of depersonalization, shouted out orders that at times seemed unintelligible. They berated anyone who didn’t understand or was slow to respond.

“Your days of moving slowly are over!” a drill instructor hollered.

Another screamed: “I am in control! Do you understand that?”

Daniel remembered something Staff Sgt. Diazdumeng had told him: “Don’t laugh too much down there, Motamedi, OK?” Daniel was prone to jokes and wisecracks. He focused on keeping a straight face, and saying nothing except “yes, sir” and “aye, aye sir,” very loudly.

The three boys had heeded advice to bring only the few items that were permitted: driver’s license, Social Security card, address book, petty cash, Bible.

The drill sergeants pawed roughly through piles of banned possessions recruits had been forced to dump into red wooden cubicles. Pens, paperbacks, chewing gum, notes from home and even Marine recruiting brochures were tossed on the floor with contempt.

Several recruits were singled out for wearing sleeveless white undershirts.

“Take off the wife beaters -- now!” a sergeant ordered.

Daniel, Daryl and Steven avoided being screamed at directly, a small triumph. They kept their expressions blank, their mouths set in hard lines, their eyes straight ahead. Steven tried to make himself seem invisible, and fought a peculiar urge to laugh out loud.

All night long and well past dawn, they followed orders. Recruits were selected at random and ordered to scream the same instructions at each of the 458 recruits processed that night.

Before being issued uniforms, each recruit was ordered to scream out his waist size, weight and height. Those who hesitated were asked, loudly, how they could fail to know such basic personal information. It was suggested that their mothers always bought their clothes.

The recruits were marched into a barbershop for the ritual boot camp haircut. The two barbers competed in speed cutting. In most cases, they sheared a head in 28 seconds or less.

Daniel, Daryl and Steven already had cut their hair short for boot camp, but that did not spare them. Afterward, they looked like circus freaks, with their pale skulls creased by pink welts from the rough path of the clippers and dotted with tufts of hair the barbers had missed.

There were hours more of processing -- hours standing in line, staring at walls, no talking, no moving. The friends did not know what to expect next, only that it would be shocking and new.

Still, they had no regrets: They yearned for their eagle, globe and anchor -- the Corps symbol pinned to the chest of each newly minted Marine. And as corny as it sounded to some of their friends, they wanted to serve their country.

Iraq and Afghanistan, where thousands of Marines are fighting and some dying, seemed part of a distant, parallel world. So, too, did the outside caldron of news and politics, where the war in Iraq was endlessly debated, and the casualties and roadside bombs were sad emblems of daily existence.

They were in a newly circumscribed world, away from home for the first time, and their lives had shrunk. They were too weary to comprehend it all. They had not slept in more than two days.

Shortly after dusk on their second night of boot camp, after being assigned bunks and instructed how to make their beds just so and how to assemble their gear and clothing in perfect military order, they slept.

--

--

About this report

With the U.S. at war, three buddies from the Santa Clarita Valley were eager to see combat. This series of occasional articles chronicles their experiences in boot camp and beyond.More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.