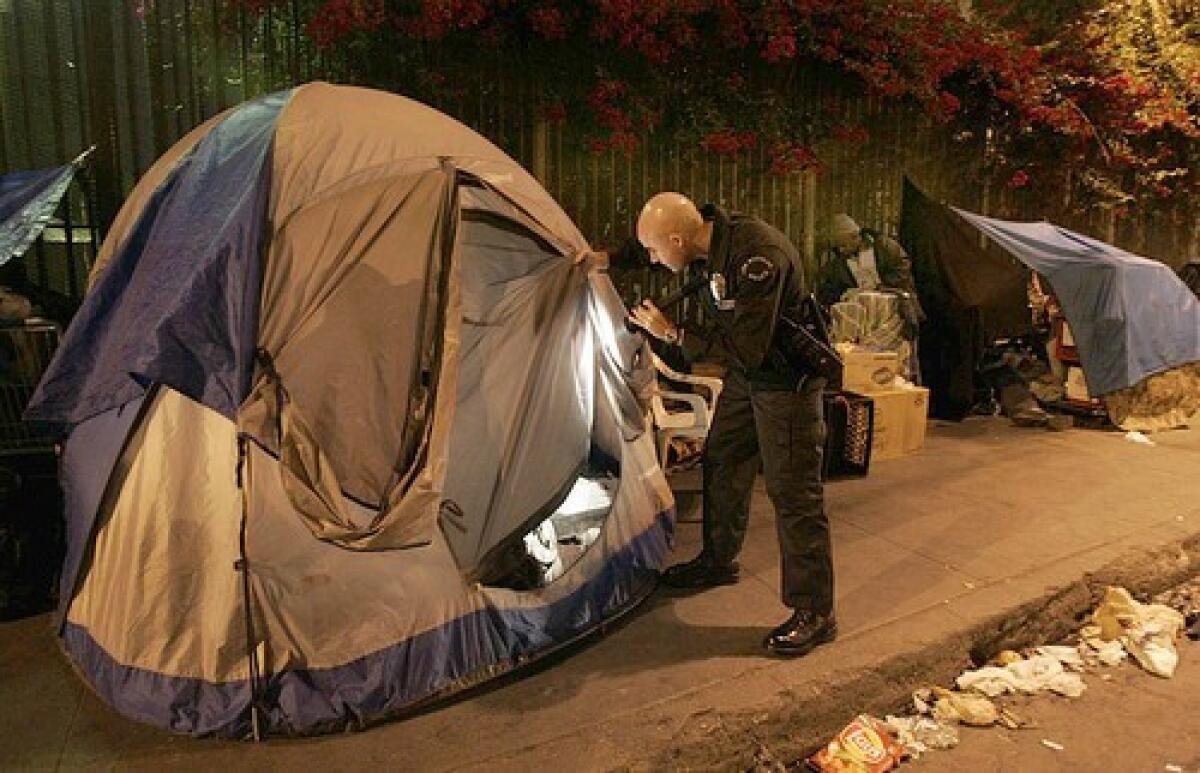

Plan Would End Homeless ‘Tent Cities’

Los Angeles officials and the American Civil Liberties Union have reached a compromise to settle a lawsuit that has prevented police from arresting homeless people who camp on the streets and sidewalks of skid row, Police Chief William J. Bratton said Monday.

Bratton, speaking to The Times’ Editorial Board, declined to provide details. But sources briefed about the compromise said it would allow police to arrest people camping, sleeping or lying on sidewalks between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m.

The sources said the settlement also would prohibit encampments at any time within 10 feet of any business or residential entrance.

Such rules would effectively prevent homeless people from creating “tent cities” that the Los Angeles Police Department and downtown business leaders have been trying to remove.

The settlement would also establish a downtown area — bounded by Central Avenue and Los Angeles, 3rd and 7th streets — where homeless people would be allowed to sleep on sidewalks at night without challenge by police or business owners.

Downtown development and business interests were immediately skeptical of the plan. They had hoped the LAPD would be given more sweeping powers to remove tents day and night, and they fear the agreement will attract homeless camps within the boundaries covered in the law.

“Any settlement that leaves people living on the street in filthy conditions and permits chaos from 9 to 6 every night in one critical area of the city is unacceptable,” said Carol Schatz, president and chief executive of the Central City Assn.

The agreement, which the Los Angeles City Council is expected to consider on Wednesday, would end a four-year stalemate that Bratton said has stymied his department’s effort to clean up skid row.

It comes after months of closed-door negotiations with a federal mediator that involved the ACLU, LAPD, city attorney’s office and the office of Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. Council approval is considered the last step in the process.

Villaraigosa has said that improving skid row by increasing affordable housing and improving homeless services is one of his top priorities. There’s also been a flurry of legislation in Sacramento aimed at reducing the “dumping” of homeless people downtown and at beefing up law enforcement.

The debate stems from a federal appeals court ruling in April. The court ruled in the ACLU’s favor, saying the LAPD cannot arrest people for sitting, lying or sleeping on public sidewalks in skid row.

Such enforcement would amount to cruel and unusual punishment because there are not enough shelter beds for the city’s homeless population, the court ruled.

Because of the lack of shelter beds, Judge Kim M. Wardlaw wrote, prohibiting homeless people from sleeping on the streets was a violation of the 8th Amendment, which bars cruel and unusual punishment.

The suit was brought on behalf of six homeless people, including Robert Lee Purrie, who has lived in the skid row area for four decades and “sleeps on the streets because he cannot afford a room in [a single-room occupancy] hotel and is often unable to find an open bed in a shelter,” Wardlaw wrote in the 2-1 majority opinion.

Purrie was cited for sleeping on the street twice before police arrested him in 2003.

Purrie spent a night in jail, was given a 12-month suspended sentence and was ordered to pay $195 in restitution and attorney’s fees.

When he was released, all his property — including his tent, blankets, cooking utensils and personal effects — were gone, according to Wardlaw’s opinion.

In dissent, Judge Pamela A. Rymer wrote that the LAPD “does not punish people simply because they are homeless. It targets conduct — sitting, lying or sleeping on city sidewalks — that can be committed by those with homes as well as those without.”

Bratton on Monday said the ACLU case has stymied the LAPD’s fight against crime and blight on skid row, which the chief said is getting worse. Before April’s court decision, he said an LAPD count found 1,345 homeless people living on skid row and 187 tents. A July 25 count found 1,527 homeless and 539 tents; a Sept. 18 count found 1,876 homeless and 518 tents.

“Wednesday will be very crucial. I hope they decide to vote in favor of this,” Bratton said. “[I am] only as effective as tools I get to work with.”

He called the situation “a very significant impendent to dealing with the problem down there.”

After the ruling, the court allowed both sides to enter federal mediation to settle their differences.

The agreement, completed during several closed-door mediation sessions over the last month, has been the subject of lobbying among City Council members in the last few days.

Councilman Jack Weiss said the agreement is crucial to the city’s moving forward to fix skid row’s many ills.

“If the ACLU and LAPD have reached an agreement, it would be foolish for the council not to follow suit,” said Weiss, who represents parts of the Westside and Valley.

“After all,” he said, “if the council continues to appeal, the process would take years, and during those years, the LAPD wouldn’t be able to enforce the law on skid row. That would be disastrous.”

But Estela Lopez, executive director of the Central City East Assn., said her organization would oppose any compromise that allowed homeless people to set up camps and sleep on the streets at any time.

She said such rules would set a dangerous precedent and worsen the crime and filth that plague the area.

“What they are saying to people in this business district is there will be an open-air drug market outside,” she said. “People coming to these businesses will be afraid.”

When Bratton took office in 2002, he vowed to apply the same “broken windows” theory of law enforcement to skid row that he successfully used in New York’s Times Square when he was chief of that city’s Police Department in the early 1990s.

But the department slowed its efforts after the ACLU filed its lawsuit in 2003.

Some of the region’s top political leaders, including Villaraigosa and Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuñez, have vowed in the last several months to make skid row a top priority. The area has long had the largest concentration of homeless people in the Western United States and is the site of about 20% of all drug arrests in the city.

The focus on skid row has also coincided with a boom in residential development downtown, with luxury lofts and condos rising on the fringes of the district.

Bratton said the compromise would allow the city to move forward immediately with a cleanup plan rather than spend years sitting by as appeals continue.

“If we wait two more years, the area is gone,” the chief said.

The LAPD is about to deploy 50 more officers to the skid row area, hoping to crack down on street crime and drug sales.

Legislators are pushing a package of bills designed to help skid row, including a $150,000 pilot program in Los Angeles County Superior Court for probation supervision and treatment of nonviolent offenders with mental health problems, substance abuse problems or both.

The legislation would also require municipalities to devise plans to help their homeless populations rather than dump them in other areas where treatment programs already exist.

Earlier this year, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors agreed to the establishment of five centers across the county that would provide temporary shelter for transients, a bid to reduce the concentration of homeless services in skid row.

Bratton said Monday that settling the ACLU suit won’t by itself solve skid row’s ills. Policing will work, he said, only if it is combined with more social services and long-term shelter for the homeless.

“We are not the solution to the problems of skid row,” Bratton said. “It is a much larger social and societal issue.”

*

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.