Before the Rumble Seat

- Share via

EIGHTEEN EIGHTY-SIX was a very big year. John Stith Pemberton invented Coca-Cola. Grover Cleveland dedicated the Statue of Liberty. King Ludwig II of Bavaria died, much to the delight of Bavarians. Also having a good year were mutton chops and diphtheria.

And on Jan. 29, 1886, pioneering automotive engineer Karl Friedrich Benz was awarded patent No. 37435, for a Fahrzeug mit Gasmotorenbetrieb, an auto car with a gasoline-powered engine.

L.A. would never be the same.

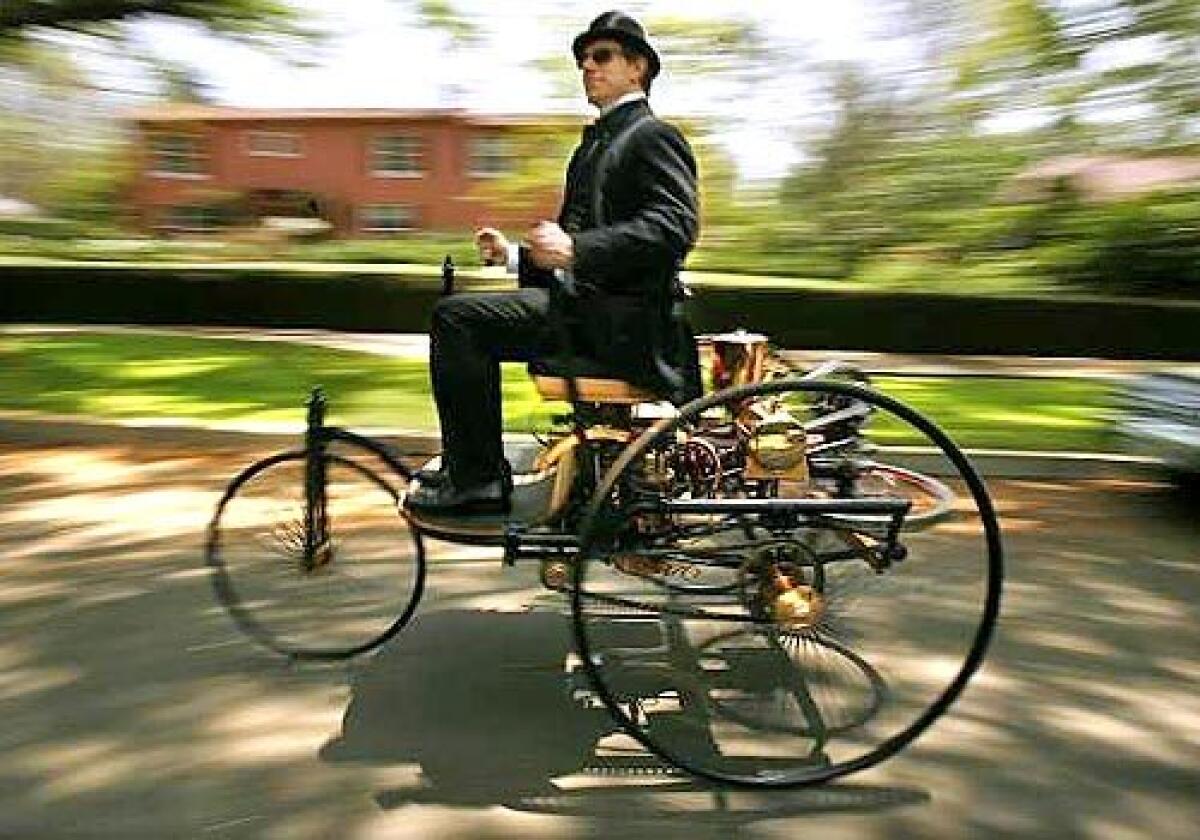

Fettled in his modest workshop in Mannheim, Germany, Benz’s Patent Motorwagen didn’t look much like a car as we know it today. To the town’s mildly alarmed burghers, it didn’t even immediately suggest a horseless carriage, whatever that was. With its spoked rear wheels and tuck-and-roll upholstered seat, it looked rather more like a park bench gone walkabout. But it was, in all the ways that matter, the first proper automobile. This was the life-evoking lightning stroke in the primordial pond, the rudimentary sorting of nucleotides from which a new species would arise. It was only a matter of time before real estate agents driving three-ton Escalades would overrun the Westside.

Automotive history begins with the 1886 Benz Motorwagen. And here I am, driving it down the quiet streets of Pasadena.

Well, at least they were quiet.

As auto critic for The Times, I’ve had my share of E-ticket rides — a Ferrari in the Alps, a Land Rover across Patagonia. I’ve gone over 200 mph in a jet-powered dragster, and not entirely on purpose either. But this — this quaint bit of blacksmithing and woodcraft, this spindly, oil-spitting cat’s cradle — this is the coolest vehicle I’ve ever gotten hold of.

And not because it’s fast. With a top speed of around 18 mph, the Motorwagen can’t outrun a decently thrown bowling ball. Of course, it feels a lot faster when you’re actually in the driver’s seat, perched in the open air at the height of a stepladder.

No, it’s cool because this is the real deal, the echt automobile, the genuine article (excepting the fact what I’m driving is actually a factory-built replica of the vehicle that’s in the Deutsches Museum in Munich). And from this over-tall seat you can feel all the familiar tinglings, the infatuating sensations of the automobile, pared to their essences. Why did the automobile succeed? And why is it still succeeding, in places like China and India, where citizens are mortgaging their meager lives to get a car? Here truth is revealed: The pleasure of cars isn’t about high-end audio systems and heated seats. It’s about mechanically multiplied self-determination. Free will with leverage.

It sure beats walking.

I wonder if, at the moment of the patent clerk’s pen stroke 6,000 miles away, the people in 1886 Los Angeles didn’t feel the wind change. Did they hear distant thunder coming across the orange groves? Did pedestrians at that moment bump into each other, mysterious auguries of the fender-benders to come?

Yes, well, probably not. The truth is, no one at the time — not even, I should say, the editors of a certain homely, recently bankrupted newspaper called the Los Angeles Daily Times — had the slightest conception how the invention of the automobile would transform L.A. from the moseying hoof-and-heel town it was to the furiously hypertensive, drunk-with-mobility monster city it is today.

Los Angeles would become the world’s first Autopia, a city whose essential metabolism — its twice-daily freeway migrations, its map-quilting pattern of municipalities, its social and cultural life — is predicated on autonomous mobility. The automobile was social engineering at its most literal.

Above all, the automobile’s increasing speed, range and comfort would endow the city with its distinctive mega-scale. Which, in retrospect, may have been not so great a mega-idea. One hundred and twenty years into the automotive experiment, the wisdom of putting nearly every living soul in 500 square miles on wheels and letting them run all over the place is clearly debatable.

Ironically, Los Angeles has forgotten more about mass transit than most cities will ever know. In 1886, the year of Benz’s patent, construction began on the nation’s first overhead electric transit line, the Los Angeles Electric Railway, a modest little route that ran through the streets of downtown L.A. A couple of decades hence, Henry Huntington consolidated various transit companies to form the Pacific Electric Railway, which at its peak had more than 1,100 miles of track and 900 of its famous Red Cars serving, in 1944, more than 109 million riders.

And then it all went away. By midcentury, freeways had begun supplanting rail lines. Tracks were paved over. Compared to the beguilements of the automobile, the electric railroad never had a chance. Mass transit? Playa, please.

Meanwhile, as the car was defining L.A., the city was returning the favor. Los Angeles is the incubator of American car culture, from hot-rodding to lowriding, from cruising to pimping. Starlets and moguls in block-long cars. Causeless rebels in ’32 Fords. James Dean in a doomed Porsche. A crazed Swede in half a Ferrari. Limo racing. Drive-by dining. Riding dirty.

That’s how we roll.

MY rendezvous with the Patent Motorwagen comes courtesy of the Mercedes-Benz company. This replica is one of 150 built in 2003 and 2004. So, yes, this isn’t literally the world’s first car, but absolutely faithful, right down to the German oak slats on the floorboards. The only practical concession is the use of a modern spark plug instead of the dinner candle-sized ceramic device that Benz invented for the purpose. The ersatz Motorwagen thus offers the identical experience that Benz and his early customers had when they climbed aboard, and occasionally the same Gott-im-Himmel aggravation.

It takes technician Nathanael Lander a sweat-soaked hour to get the machine started as Pasadena’s soaring heat and humidity foil his best attempts to find the proper fuel-air mix. “These were toys for the extremely wealthy,” Lander says before giving the 75-pound cast-iron flywheel another futile heave. “Not to mention, you had to be really mechanically inclined to get one of these on the road.”

Between huffing and puffing, Lander — who has a degree in historic automotive restoration — marvels at the plucky machine. “Everything in the modern car is in there,” he says. “Benz just nailed it.”

Finally, after prolonged fiddling, Lander gives the flywheel another spin and the engine catches fire, building slowly in rpm — whack! whack! whack! whack! — and gradually, Lander adjusts the amount of air going into the carburetor. While the engine is warming up, he shows me the controls. The steering is by way of a wooden-handle lever connected by a steering rack, more a tiller than a steering wheel. Because the engine runs at a constant speed — as opposed to a modern car, where the revolutions per minute rise and fall depending on the workload — the only other control is a long lever that engages the engine belt to the axle. To stop, you pull the lever back. This disengages the engine belt at the same time it cinches a circular brake pad around a drum.

With Lander’s help, I mount the machine, using the little cast-iron step below the slatted floorboard for a leg up. The seat is comfortable, rather like a piano bench with arm rests. Carefully feathering the lever in my left hand — engaging the engine belt too quickly could kill the engine — I pull out into the street.

Wow. This thing is fun! I’m amazed at how lively the little tallyho is. When I swing the steering lever left and right, the carriage wriggles back and forth like a fish swimming upstream, the engine thumping merrily with a Mike Mulligan exuberance. It wants to go. At maximum engine speed (about 300 rpm) the engine is producing three-quarters of a horsepower (for reference, the average 750cc sport bike produces about 80 hp).

Another thing: Once you are seated you can’t actually see much of the vehicle. At speed, it seems as though you are being conveyed along by some noisy, unseen force. This is the view of the road that hood ornaments have.

To the dog walkers and leaf blowers out on this sunny morning, the Patent Motorwagen must seem comically primitive, all whirring spokes and madcap machinery. With its polished brass reservoirs (coolant, fuel, carburetor) in the back, the Motorwagen looks as if it’s assembled from a collection of Williams-Sonoma cookware.

It’s hard for modern eyes to appreciate how advanced the Motorwagen was. This thing was the hyper-tech, code-black DARPA program of Imperial Germany.

For reference, consider the state of automotive art at the time. French inventors — with names like Bollee, Serpollet, Comte De Dion — were conceptually trapped by what they were familiar with: rail engineering. Their massive steam-powered devices were essentially trackless locomotives. The same imaginative hamstringing affected Gottlieb Daimler, another founding father of the automobile. With the help of the brilliant Wilhelm Maybach, Daimler had created his own motorwagen (his patent was issued a mere seven months after Benz’s) but Daimler’s machine was comparatively a behemoth, a four-seat rig with wooden cartwheels and huge exposed gears worthy of a clock tower. Literally, a horseless carriage.

Benz’s machine — lightweight, nimble, essential — was a complete break from the past, the automobile qua automobile. It was a beautiful brass-and-steel dragonfly amid crows.

Actually, as Benz himself found out, his contraption could be a little too much fun. The first thing he did during testing was to crash it into a brick wall. Also, because of the inherent instability of a three-wheel configuration, the Motorwagen will happily tip over if you corner with too much speed. I’m at the controls only a couple of minutes before I corner hard enough to pick up the inside rear wheel. Whooaaa!

WHAT’S even more remarkable is that the Benz Motorwagen is so recognizably a car, comprising technical antecedents of the machines we know today.

Though compared to modern engines Benz’s one-cylinder number has a diagrammatic simplicity, it works the same. It’s liquid cooled, for instance. There’s a flywheel and a crankshaft. On the belt drive’s shaft is an oblong steel lobe — a cam. As it rotates, it causes a rod to saw back and forth, opening and closing a small window between the cylinder and the carburetor, thereby admitting the fuel-air charge into the cylinder. This is the intake valve. The lobe also actuates a pushrod that operates the exhaust valve, a poppet-style device just like ones in a 2007 Mercedes-Benz engine.

Meanwhile, another lobe on the belt drive shaft opens and closes a switch that fires the spark plug at the right moment in the combustion cycle. Voilà. Ignition timing.

If it sounds as if it would take an expert machinist to operate it, well, Benz might have thought so too, until his wife borrowed the family car without telling him. On a summer morning in August 1888, Bertha Benz got up early, loaded her sons Eugen and Richard on board and set out in the Motorwagen for her mother’s house in Pforzheim, a journey of some 50 miles. Karl Benz awoke to find a note his wife had left saying she was going to visit Grandma. He must have been panicked. The Motorwagen had never been tested for more than a few miles.

That evening, Bertha wired Karl to say they had arrived safely. But not, as it turned out, without incident. Bertha was obliged to clean out a clogged fuel line with her hatpin and mend an ignition wire with one of her garters. When the brake shoe started to give way, she stopped at a farrier’s in Bauschlott for a block of leather to replace it. In Wiesloch, she stopped at an apothecary to fill up on benzene (this pharmacy still bills itself as the world’s first filling station). And so it happened that the world’s first motorist was, in fact, a woman.

THE automobile was fun. It was easy. It was clean and indefatigable. Unlike a horse, it had no mind of its own — though owners of some British sports cars would argue that point. Perhaps most important, the invention of the automobile coincided with the discovery and exploitation of the planet’s vast endowment of oil, the buried recrudescence of life on Earth a billion years in the making. Oil, too, had a hand in shaping Los Angeles.

What I think about as I pilot the little park bench along the streets of Pasadena — whack! whack! whack! whack! — is the fantastic history that played out after the Motorwagen, the pandemic of mechanical art and ingenuity it inspired. I’m overwhelmed by a sense of incipience, and also a touch of remorse. The automobile has not been the unalloyed blessing that Benz might have hoped. It may be that the automobile was too fun, easy and delightful for our own good.

*

1886 Benz Patent Motorwagen

Original price: 600 imperial Deutsche marks for the prototype

Price, as tested: about $60,000

Powertrain: Gas-powered 0.954-liter, four-stroke, water-cooled one-cylinder horizontal engine with open crankcase and cast-iron flywheel; pushrod actuated, with sliding intake valve and poppet exhaust valves; belt-drive to countershaft with idle and fixed disc and integrated differential; rear-wheel drive with fixed-ratio chain drive.

Horsepower: 0.75 at 400 rpm

Curb weight: 584 pounds0-18 mph:

45 secondsWheelbase:

57 inchesOverall length:

106.3 inchesHeight: 57.1 inchesFuel economy:

25 miles per gallonFinal thoughts: A star is born

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.