Iran’s nuclear ambitions on hold, U.S. agencies conclude

WASHINGTON — U.S. intelligence agencies have concluded that Iran halted its nuclear weapons program in 2003 and that international pressure has compelled the Islamic Republic to back away from its pursuit of the bomb.

The new findings represent a retreat from a fundamental U.S. assumption about one of its main adversaries, and an admission that a central component of previous intelligence estimates on Tehran’s nuclear program was wrong. But the report makes it clear that Iran could decide at any point to resume its efforts to develop a nuclear weapon.

The assessment, which represents the consensus of the 16 U.S. intelligence agencies, including the CIA and the National Security Agency, is expected to have major implications for the ongoing debate over whether to confront Iran militarily or through diplomatic means, an issue that has been a source of friction within the Bush administration and with some members of the international community.

As recently as October, President Bush was warning that a nuclear-armed Iran could lead to World War III, and Vice President Dick Cheney threatened Tehran with “serious consequences” if it did not abandon its nuclear program.

Senior U.S. intelligence officials said that Bush and Cheney were briefed on the intelligence estimate on Iran Wednesday, but declined to say when they were informed that Iran had halted its nuclear weapons work.

Iran stopped developing nuclear weapons designs and ended covert efforts to produce highly enriched uranium suitable for use in a bomb, the report says.

“We judge with high confidence that in fall 2003, Tehran halted its nuclear weapons program,” the report concludes.

And it says the intelligence community judged “with moderate confidence” that Tehran had not restarted the program as of mid-2007 and did not have a nuclear weapon.

At the same time, the findings, which will be shared with Israel and other U.S. allies, note that “Tehran at a minimum is keeping open the option to develop nuclear weapons.”

The report says that despite threats of international economic sanctions, Iran resumed installing centrifuges at Natanz in 2006, but “still faces significant technical problems operating them.”

The Natanz installation is part of Iran’s much-publicized program to enrich uranium for nuclear reactors capable of generating electrical power, but the degree of enrichment necessary for so-called weapons-grade uranium is far higher than that of the fuel it is able to produce there.

The report also says that Iran is unlikely to be able to make enough highly enriched uranium for a bomb before 2009 at the earliest, and possibly as late as 2015. The acquisition of weapons-grade material is considered the main obstacle to Iran building a bomb.

The intelligence estimate was contained in a report titled “Iran: Nuclear Intentions and Capabilities.”

The key judgments of that report were declassified and released Monday. The bulk of the report, which is said to span nearly 140 pages, remains classified.

The report acknowledges that emerging evidence has forced analysts to alter their views on Iran’s intentions and capabilities, as well as its susceptibility to outside pressure.

“Tehran’s decisions are guided by a cost-benefit approach rather than a rush to a weapon irrespective of the political, economic and military cost,” according to the report. Overall, it says, Iran “is less determined to develop nuclear weapons than we have been judging since 2005,” and “may be more vulnerable to influence on the issue than we judged previously.”

As a result, the report could give new leverage to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates and others within the administration who have pushed for diplomatic initiatives over military strikes against the Islamic regime.

Indeed, the document suggests, “some combination of threats of intensified international scrutiny and pressures,” along with opportunities for Iran to achieve its regional goals, could “prompt Tehran to extend the current halt to its nuclear weapons program.”

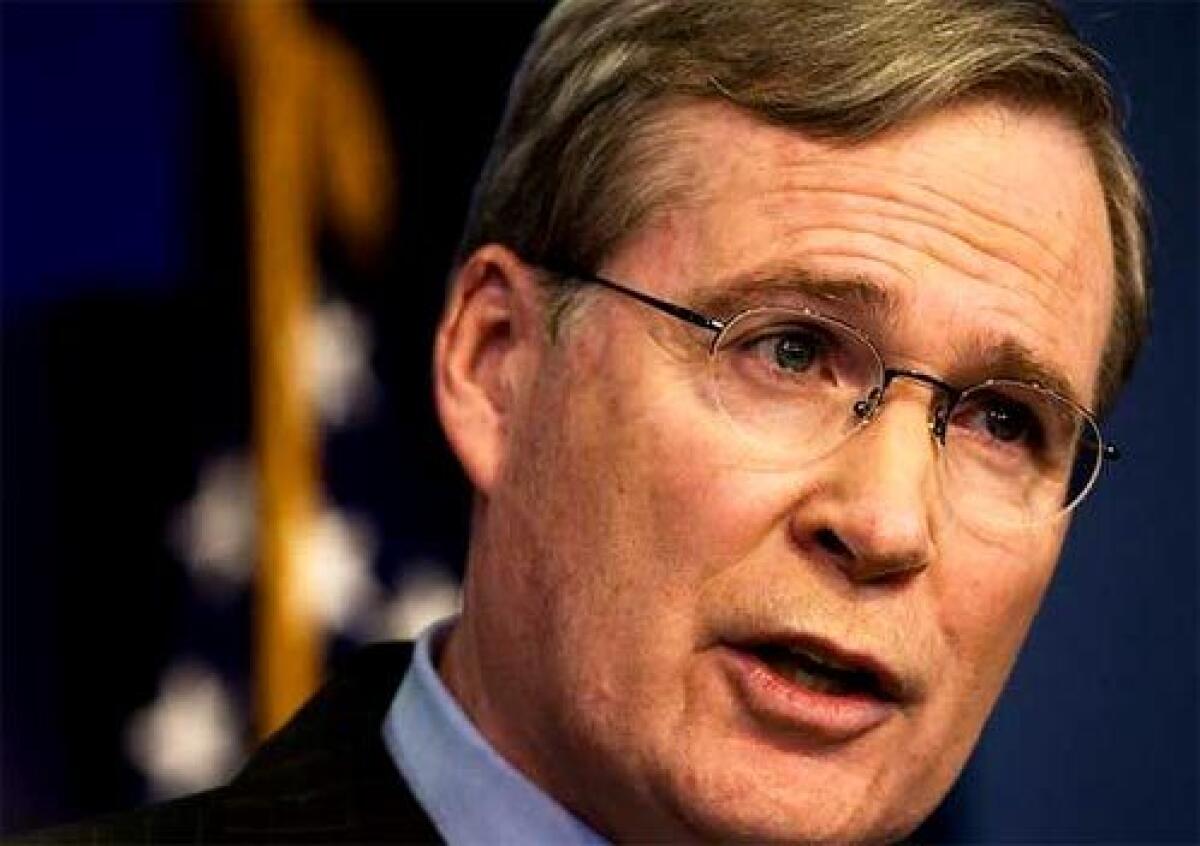

At the White House, national security advisor Stephen Hadley described the report as “good news” that validated the administration’s approach to keeping Iran from developing a nuclear weapon.

“It tells us that we have made some progress in trying to ensure that that does not happen,” Hadley said. “But it also tells us that the risk of Iran acquiring a nuclear weapon remains a very serious problem.”

From Vienna, a senior official at the International Atomic Energy Agency said the report “basically validates what the IAEA has been reporting: There is no indication of a secret program, though we can’t rule it out.”

The report comes five years after a hastily assembled National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq erroneously concluded that the country had chemical and biological weapons stockpiled and was aggressively pursuing nuclear weapons.

That document, cited by the Bush administration in making the case for invading Iraq, proved to be wrong on almost all of its major findings.

In the case of Iraq, intelligence agencies were also accused of succumbing to interference from officials within the Bush administration. Leading members of Congress said the substance of the new Iran report suggests that the community is now better insulated from such pressures.

“This demonstrates a new willingness to question assumptions internally, and a level of independence from political leadership that was lacking in the recent past,” said Sen. John D. Rockefeller IV (D-W.Va.), chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee.

Indeed, the new report goes so far as to include a table that makes side-by-side comparisons between its assessments from 2005 and the superseding judgments released Monday. At the top of the table is language from an assessment two years ago that said Iran was “determined to develop nuclear weapons.” It was set against the current view that all work on nuclear weapons stopped in 2003.

Senior intelligence officials said that the National Intelligence Estimate, or NIE, on Iran had been in the works for more than a year, but that new information and analysis prompted major revisions of the document within the last three months. The officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity, declined to elaborate.

A former U.S. official familiar with intelligence on Iran said that one critical new piece of information stemmed from an intercepted call involving a senior Iranian government official who was heard “complaining that the program was suspended.”

One of the senior U.S. intelligence officials who discussed the matter cautioned against concluding that a single piece of information, or “Rosetta stone,” had surfaced. Instead, the officials pointed to a number of developments, including Tehran’s decision to allow foreign journalists to visit the country’s nuclear facility at Natanz last summer.

The centrifuges at Natanz are designed to produce low-enriched uranium, officials said, which is not suitable for nuclear weapons. But intelligence officials said that the expertise that Iranian scientists had developed working with those centrifuges could be exported to other facilities designed to make weapons-grade material.

Advocates of diplomacy seized on the new Iran report, saying that it makes a compelling case against military intervention.

“This is a blockbuster development and requires a wholesale reevaluation of U.S. policy,” said Jon B. Wolfsthal, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “This NIE suggests that outside pressure has turned off Iran’s nuclear weapons program. This is the piece of evidence that was missed in the case of Iraq.”

But proponents of a more forceful approach with Iran scoffed at the suggestion that diplomacy could dissuade the country from its nuclear ambitions.

Developing nuclear weapons “is a strategic decision they’ve been pursuing for 20 years,” said John R. Bolton, formerly the Bush administration’s ambassador to the United Nations. To give weight to a single intelligence estimate, he said, “would be a mistake.”

Asked what effect the document might have on the debate within the Bush administration, Bolton said: “There really isn’t any debate. Secretary Rice and Secretary Gates have fundamentally won. This is an NIE very conveniently teed up for what the administration has been doing.”

In some respects, however, the intelligence estimate could be viewed as providing evidence that the aggressive policies of the Bush administration were effective in putting pressure on Tehran.

Senior intelligence officials said they could not establish that it was directly a result of Washington’s policies, noting that Iran appears to have halted its program around the time of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Libya’s decision to abandon its nuclear program, and the unraveling of the nuclear proliferation network led by Pakistani scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan.

These things “created an atmosphere that clearly led to this decision” by Iran, said one of the senior U.S. intelligence officials.

Officials said the evidence was clearer that international pressure and the threat of isolation pushed Iran to halt the program.

The intelligence estimate concludes that Iran’s military was pursuing nuclear weapons until the fall of 2003 as part of a program that was kept secret from the international community for decades.

Iran probably would use covert facilities, not those that it has declared to international inspectors, for the production of highly enriched uranium for a weapon, the report said.

“We assess with high confidence that Iran has the scientific, technical and industrial capacity eventually to produce nuclear weapons if it decides to do so,” the report concludes, noting that “only an Iranian political decision to abandon a nuclear weapons objective would plausibly keep Iran from” eventually doing so.

Donald M. Kerr, the second-ranking U.S. intelligence official, said the U.S. government decided to release the key findings because they had changed so significantly from previous releases and public testimony from top intelligence officials.

“Since our understanding of Iran’s capabilities has changed, we felt it was important to release this information,” Kerr said.

Times staff writers Maggie Farley at the United Nations and Julian E. Barnes and Bob Drogin in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.