The Supreme Court fight has also set up a battle between Joe Biden and Mitch McConnell

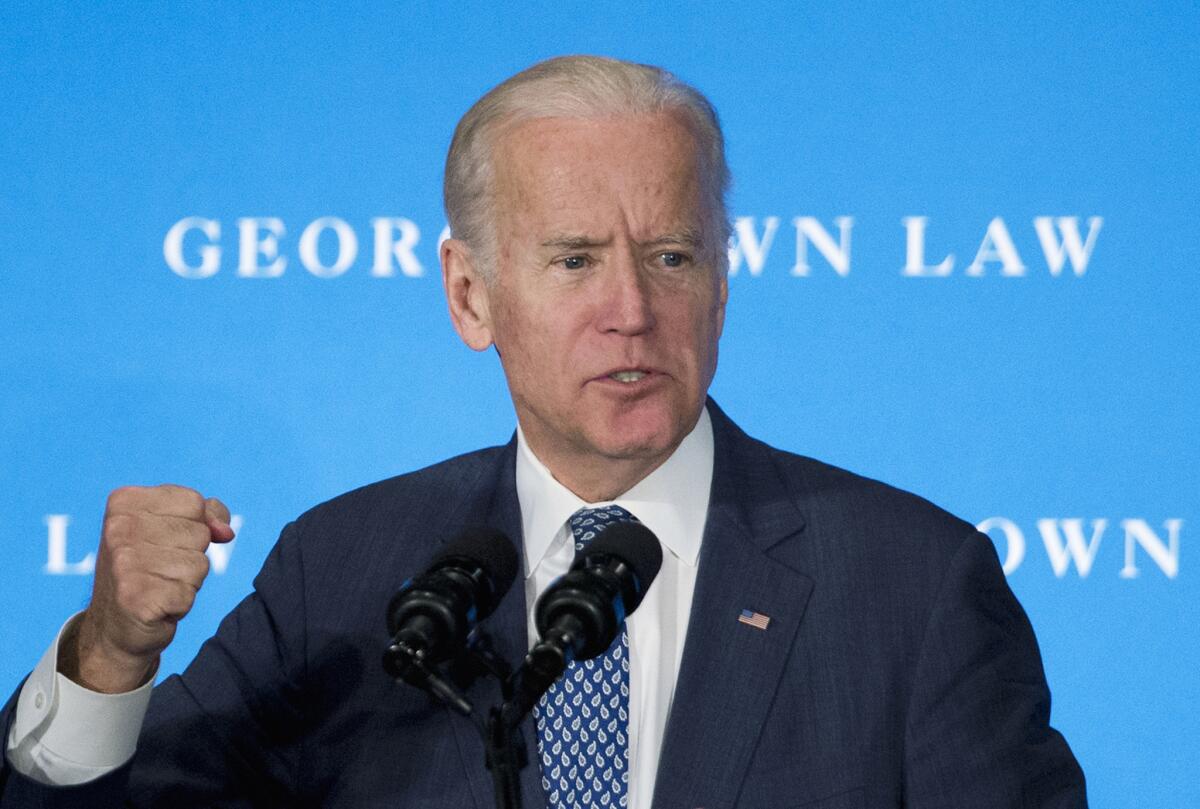

Vice President Joe Biden speaks about the Supreme Court vacancy and confirmation process at the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington on Thursday.

Reporting from Washington — The pitched battle over a vacant seat on the Supreme Court is not only the latest drama between President Obama and a Republican Congress, but also increasingly a test of wills for two veterans of the U.S. Senate.

Call it the Biden Rule versus the McConnell Precedent.

For Vice President Joe Biden, who spent half of his 36-year Senate career as the top Democrat on the Judiciary Committee, Republicans’ refusal to consider Obama’s high-court candidate marks a further breakdown of the norms and traditions of an institution he still reveres.

His longtime Senate colleague Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) had vowed to restore the Senate’s great deliberative tradition as he campaigned in a successful bid to become majority leader in 2014. But now McConnell is using Biden’s own words to underscore his strategy to obstruct the confirmation process by denying a hearing and vote to Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland.

He and other Republicans point to a speech Biden made as a senator nearly a quarter-century ago in which he cautioned a Republican president against trying to fill a Supreme Court vacancy in a presidential election year.

After video of the speech was unearthed, Republicans dubbed his assertion the Biden Rule and said it applies now just as the Delaware senator argued it did then: putting off a politically charged confirmation fight in the midst of a heated presidential election was not only sound, but fair to the nominee.

On Thursday, the vice president offered his most vigorous defense yet on the issue, arguing the GOP was not only misrepresenting what he said but ignoring what he did as chairman of the Senate’s judiciary panel, which oversees confirmation hearings for federal judgeships.

“There is only one rule I ever followed in the Judiciary Committee,” he said in a speech at Georgetown University’s law school. “The Senate must advise and consent. And every nominee, including Justice Kennedy in an election year, got an up-and-down vote. Not much of the time. Not most of the time. Every, single, solitary time.”

But he also broadened his critique to accuse Republicans of launching the country into “a genuine constitutional crisis born out of the dysfunction of Washington.”

It was an implicit challenge to McConnell, who once accused Democrats of turning the Senate into “a veritable graveyard for good ideas.”

As he campaigned to end eight years of Democratic control of the Senate in 2014, McConnell repeatedly accused the party of putting its own political interests above the national interest, and its leaders of shielding senators from tough votes to help them get reelected.

“There’s a time for making a political point, even scoring a few points -- I know that as well as anybody,” he said in a speech that year that laid out his vision of a Republican Senate. “But it can’t be the only thing we do here.”

After he realized his goal to become majority leader, McConnell said his first task was to “get the Senate back to normal.”

The death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February put him on a different track. He swiftly ruled out the possibility that the Senate would consider an Obama-nominated replacement, later saying he wouldn’t even meet with the nominee.

McConnell argued that the public should be heard through its vote for president before a seat is filled that could tip the balance of the high court for generations. And he insisted he had precedent -- set by Biden.

In June 1992, amid speculation that a liberal justice might resign, Biden reflected on the recent tumult of Supreme Court confirmation processes to caution then-President George H. W. Bush.

“If the president goes the way of Presidents Fillmore and Johnson and presses an election-year nomination, the Senate Judiciary Committee should seriously consider not scheduling confirmation hearings on the nomination until after the political campaign season is over,” he said then.

----------

FOR THE RECORD

March 24, 8:49 a.m.: An earlier version of this article misstated how long ago Vice President Joe Biden gave a speech from the Senate floor that has been central to the GOP’s strategy in the Supreme Court nomination battle. The speech was given 24 years ago, not 22 years ago.

----------

Adopting Biden’s argument is not without risk. Some Senate Republicans have become increasingly public in expressing reservations about the strategy, saying they would be willing to meet with Garland or calling outright for a confirmation hearing.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), a member of the Judiciary Committee who said he supports McConnell’s approach, nonetheless has noted that it sets a precedent that a Republican president might have to live with. He also warned that if Hillary Clinton were to be elected president this fall, she might pick a more liberal nominee than Garland.

But that line of thought is a gamble for Senate Republicans. The GOP base “is not open to this argument at all,” said Francis Lee, a University of Maryland professor who studies partisanship in the Senate.

“What McConnell’s doing here with Garland [is] he’s protecting his members from tough votes,” she said. “No matter what the politics might look like in terms of general public opinion, it divides the Republican Party. ... They want to see this stopped. They do not want to see the ideological direction of the Supreme Court changed.”

Biden, in his speech Thursday, warned of the long-term impact such a Republican posture could have, saying it was already affecting U.S. standing in the world.

“Obstructionism is dangerous and it is self-indulgent,” he said. “For the sake of both parties, for the sake of the country, for the sake of our ability to govern, it’s got to stop.”

McConnell’s office said Biden was on “a cleanup mission” given how politically problematic his past speech has been. Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, now the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, said it was Biden who is misrepresenting his old remarks.

“The American people should be provided an opportunity to weigh in on whether the court should move in a more liberal direction for a generation, dramatically impacting the rights and individual freedoms we cherish as Americans,” he said.

Follow @mikememoli on Twitter for more news out of Washington.

ALSO:

Sanders on California’s primary: ‘You’re going to see me here more than you feel comfortable with’

Bernie Sanders rocks the Los Angeles faithful in a rally at the Wiltern

These Republicans know the presidency shouldn’t be reality TV. But they’ll vote for Trump anyway

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.