It had already been a busy day for the Las Vegas coroner when the shooting started. It left him a changed man

- Share via

Reporting from Las Vegas — The coroner slowly slipped off his shoes, just like he’s done most mornings over the past year, and took a seat on the floor in the small room.

Legs crossed and palms raised, he closed his eyes. Soothing sitar music played softly as Elizabeth Scherwenka asked him to focus on his breathing.

Inhale. Pause. Exhale. Pause. Deeper.

Take eight breaths and be conscious of each and every one, she instructed. Scherwenka told him to notice his inner state as a golden ball of light.

His chest rose and fell beneath his blue Clark County Coroner shirt. John Fudenberg felt the world slowing down, taking him away from that first day in October when his heart, mind and body raced amid the madness.

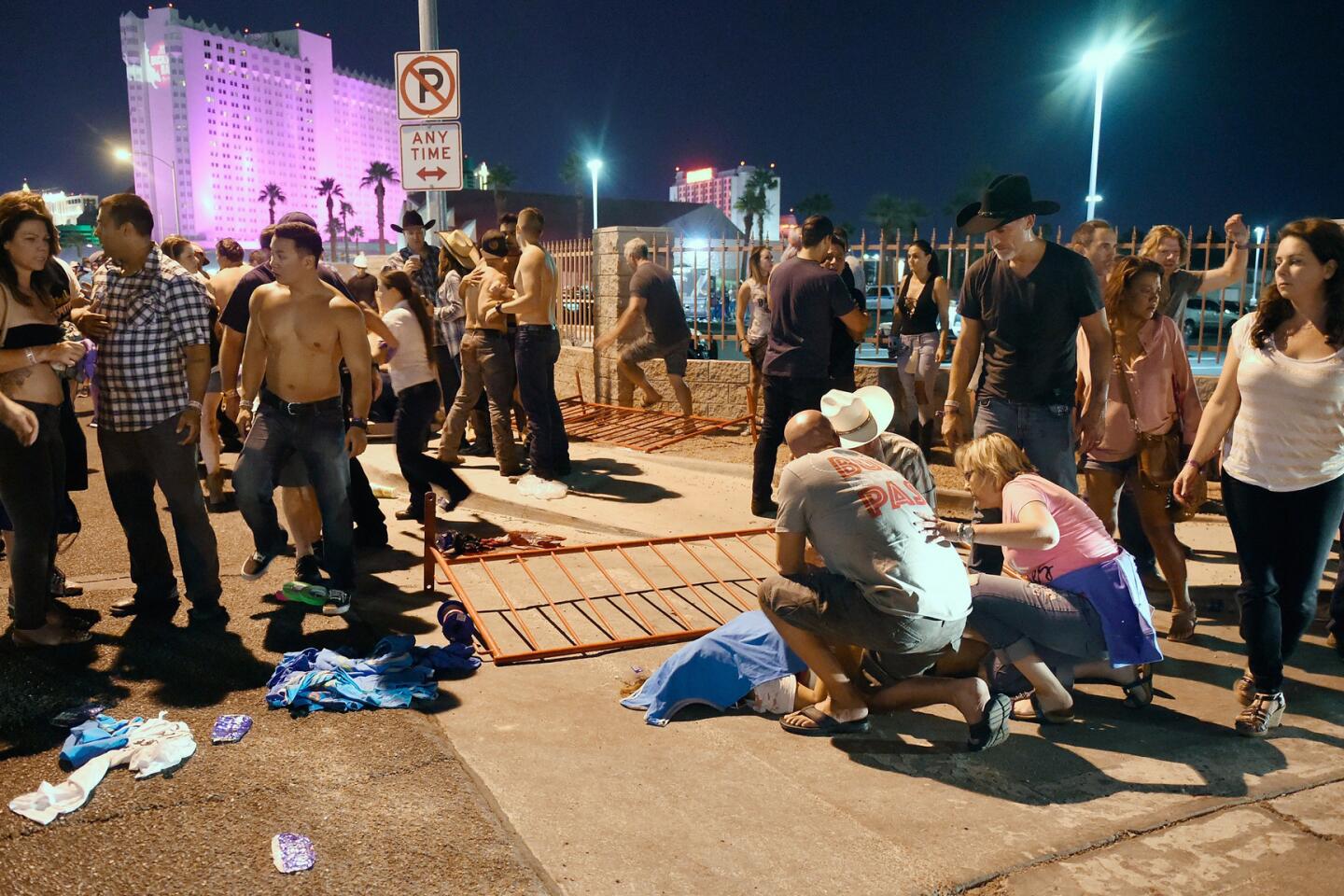

Nobody knew Oct. 1 would be the day Stephen Paddock would take aim from his suite on the 32nd floor of Mandalay Bay Hotel and Casino and lay waste to the Route 91 Harvest country music festival with hundreds of rounds from semiautomatic rifles. He would kill 58 — the worst mass shooting in modern American history.

That Sunday had been slightly busier than normal, with 14 bodies examined at the coroner’s office. There had been two suicides. Four drug overdoses. A few vehicle accidents, including one in which three children were killed.

But it was later in the evening now and he was in the back seat of an Uber along with his friend, Jason Cheney. The two were headed home after watching a Vegas Golden Knights preseason hockey game. His phone buzzed. It was an investigator from his office.

Fudenberg heard the gunshots through his phone. Popping sounds. He can’t forget them. His protocol has been to show up at any scene if there were two or more dead. The investigator told him there were at least 20. Maybe more.

Cheney saw his friend absorb the news. His face locked in an expression he’d never seen.

“The change in him was instant,” Cheney said. “We had been talking and joking and suddenly, it was gone.”

On Oct. 1, 2017, a shooter sprayed the Las Vegas Strip with more than 1,000 rounds of gunfire, killing 58 and injuring hundreds at an outdoor concert. Video and 911 recordings captured the horror as it happened.

Fudenberg was dropped off first by the driver. Cheney said he wouldn’t see him again until he was on television, giving updates on the deceased. It would be two more weeks before he would see his friend again in person. Over that dinner, Cheney would see some cracks.

The veteran coroner would cry. It wouldn’t be the last time.

Fudenberg, 49, is from Minnesota and his staff is acutely aware of his “Minnesota nice” persona. There is the Midwestern accent that has ceded only slightly despite nearly three decades in Nevada. He is known to bring in doughnuts or bagels for the staff on the first working day of the month. He hand-writes birthday and anniversary cards for his staff of about 70.

Nicole Charlton, administrative assistant, said during the morning meetings that if a staff member is having a birthday, he leads them in singing.

“We’re very close-knit,” she said.

Which is why it wasn’t unusual for Charlton to suddenly be driving to his house that night. He had asked her to pick him up right away and drive him to the Las Vegas Strip. She knew it was going to be a long night and cancelled a surgery scheduled for the next morning.

As she drove him to the staging area, he was on the phone the entire trip.

That would be normal for days. Weeks, even. He said it was unrelenting as elected officials put pressure on his team to provide updates on the victims and answers about Paddock. Fudenberg said he even got a call from the White House. He didn’t remember who it was.

Arriving at a staging site, Clark County Undersheriff Kevin McMahill arranged to get Fudenberg to the concert venue across the street from the Mandalay Bay. McMahill remembered it was windy.

He also remembered what it looked like and what it sounded like in the open field. Just hours before, it had been a rollicking concert.

“It was surreal and the most eerie scene I’ve ever been at,” McMahill said. “There were victim’s cellphones ringing and the lights were flashing on them. It was as if 22,000 people dropped everything and ran away.”

McMahill has known Fudenberg since the 1990s, when McMahill was a marshal with the city of Las Vegas. In the three years since Fudenberg became the coroner, McMahill has worked with him dozens of times.

Nothing like this one, however. The largest number of deaths his office had dealt with was in 2009 when seven Chinese nationals were killed en route to the Grand Canyon.

Fudenberg walked the concert grounds, Charlton next to him. Wind blew plastic cups that hit him in the shins. He saw food still cooking on grills. His team set up a laptop and went to work.

By 3 a.m., refrigerated trucks began arriving to take the victims to the coroner’s office. It took 12 hours to remove all the victims.

The day after the shooting, the normal case load in Vegas resumed. Nine people died from a variety of causes, including a pair of overdoses, two suicides and a car accident. But the shooting on the Strip had become all-consuming at the coroner’s office.

Meetings were scheduled. A centralized location was set up for friends and families of those trying to find out if a person was dead or not. Fudenberg was now running on adrenaline. He had put a cot in his office, but he hadn’t really slept.

On the other side of the country, Orange County Medical Examiner Joshua Stephany had been watching the news unfold from his office in Orlando, Fla. Just a little more than a year before, his office had handled 49 people shot and killed at the Pulse Nightclub — at that time, the largest number of casualties in a mass shooting in modern American history.

Stephany wanted to support Fudenberg, so he emailed him. He remembered how overwhelming it was after Pulse. He knew Fudenberg wouldn’t have time to take a call.

“Not a lot of us have gone through this,” Stephany said. “I wanted to be there for John — if he had any questions or just needed to talk. I just wanted to let him know I was there for him.”

At the coroner’s office, where medical examiners studied gunshot wounds and tried to identify the victims, they were running out of room. There were so many bodies, they had to use a second storage area. Paddock’s body was kept separate from the victims. It is standard protocol to keep a suspect separate out of respect for the victims. “I absolutely made sure we did it with him,” Fudenberg said.

Fudenberg knew determining the cause of death for the 58 wouldn’t be complicated. When the coroner’s office released the autopsy reports three months later, it was as he suspected: All had died from gunshot wounds. The difficult part, he knew, would be telling relatives.

He talked to his staff about the process. There would be teams that would handle notifying next of kin — many of whom had begun arriving in Las Vegas, desperate for news. They had been gathering at the convention center, where the Family Assistance Center had been established.

Fudenberg told his staff to take care with how they talked to the families.

“Each one of those notifications consisted of five to 10 family members walking into a space and hearing the worst news they ever heard in their life,” Fudenberg said. “The staff did one or two notifications per shift. That was enough. When you’re doing four or five per hour for multiple hours, you can imagine how emotionally taxing that is.”

Mary Jo Von Tillow remembered hearing the news about her husband, Kurt Von Tillow. He was a man who literally wore his patriotism — fancying American flag-themed clothing and getting emotional while singing the national anthem. “He was so patriotic and loved this country so much,” she said.

She knew her husband was one of those who’d been killed. Her biggest fear was not knowing where his body was.

“I didn’t want him laying out there, in the sun, all by himself,” she said. “Then the coroner told us, ‘No, we have them all here. They’re all here.’ It was very comforting, in an odd way.”

The notifications was grueling. Fudenberg did several on his own. One was a large family. About 10 of them.

He began to tell them — words that could never be taken back. Words that would haunt them forever. He started to feel the tears. Heaviness in the chest. Fudenberg summoned up his years of professional training to try and push it back down.

Then he heard the little girl. “No. No. Mommy.” She was wailing uncontrollably.

The coroner cried.

Paul Fudenberg was watching the aftermath of the shooting unfold on television from his home in Minneapolis. He called his brother after the tragedy, but wouldn’t see him until two weeks later when John flew back to Minnesota. It was his first break from the shooting.

It was a funeral for a close friend from high school who had died of breast cancer. It was a quick trip — two days. There was still a lot of work to do in Las Vegas. His phone was still constantly buzzing.

“That wasn’t easy,” Paul said. “But it also gave him a chance to be with some friends.”

Meditation has helped John through the past 12 months, he said, along with support from his teenage daughter and ex-wife.The meditation, however, was a new experience and he admitted skepticism at first. Now, he does it three or four times a week.

It quiets his mind. He can’t forget the night and following days and weeks. He remains the coroner who oversaw the identifications and notifications after the largest mass shooting in modern American history. He has had staff leave — too emotionally drained from the experience. He’d been sued by media outlets to release autopsy reports. The office went on a lock-down the day after the shooting and has had rigid security clearances ever since.

“There isn’t a day that goes by that doesn’t involve the shooting somehow.”

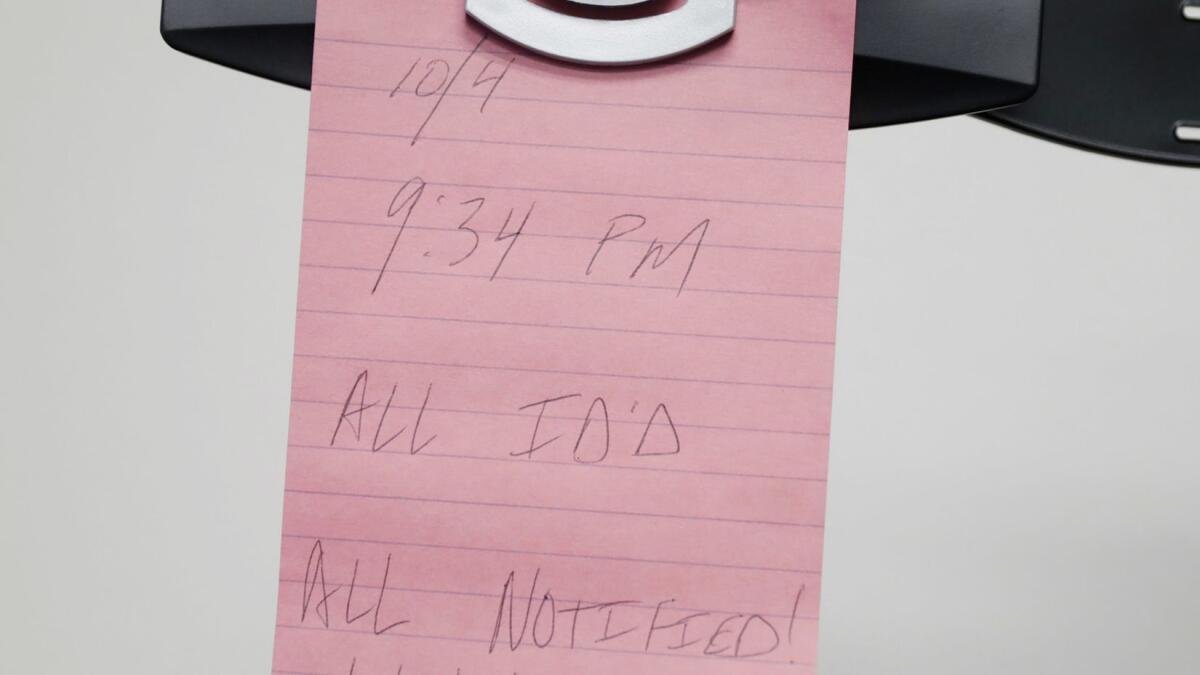

And there is another reminder. It’s small and simple, clipped to the side of his computer. A pink piece of paper from a time that he said still often feels like yesterday. It’s written in ballpoint pen: “10/4. 9:34 p.m. ALL ID’D. ALL NOTIFIED!!!!!!!”

Fudenberg reads it aloud in his office. It is quiet for a moment. He exhales.

[email protected] | Twitter: @davemontero

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.