In tale of two cities, parts of Houston survived untouched, while others begin flood cleanup

Reporting from Houston — A week after Hurricane Harvey lashed Texas with record rainfall, President Trump returned to the Lone Star State, as storm survivors began to return to their neighborhoods and stark divisions between those who lost everything to the floodwaters and those who escaped relatively unscathed were on display.

Parts of west Houston were still reeling on Saturday. In residential neighborhoods near the Addicks Reservoir, which overflowed during the storm, residents relied on boats including canoes and kayaks to run errands and commute to work. Some had power; some didn’t. Some of the single- and two-story brick homes remained swamped with several feet of fetid water; others were dry.

For the record:

9:17 a.m. Jan. 9, 2025Earlier versions of this report said that Beaumont, Texas, has a population of just over 18,000. Beaumont’s population is about 118,000.

“It’s a tale of two cities right now,” said Pete Carragher, 64, a geologist who returned home by canoe with his son-in-law, who lives nearby, to check on their houses and fetch supplies.

“You go a mile north and you would never know anything had happened, apart from the extra lines at the gas stations and the few shops being shut,” Carragher said. He stood in knee-deep water, dressed in waders and boots. “It’s just if you’re in this floodplain areas here, it’s devastating.”

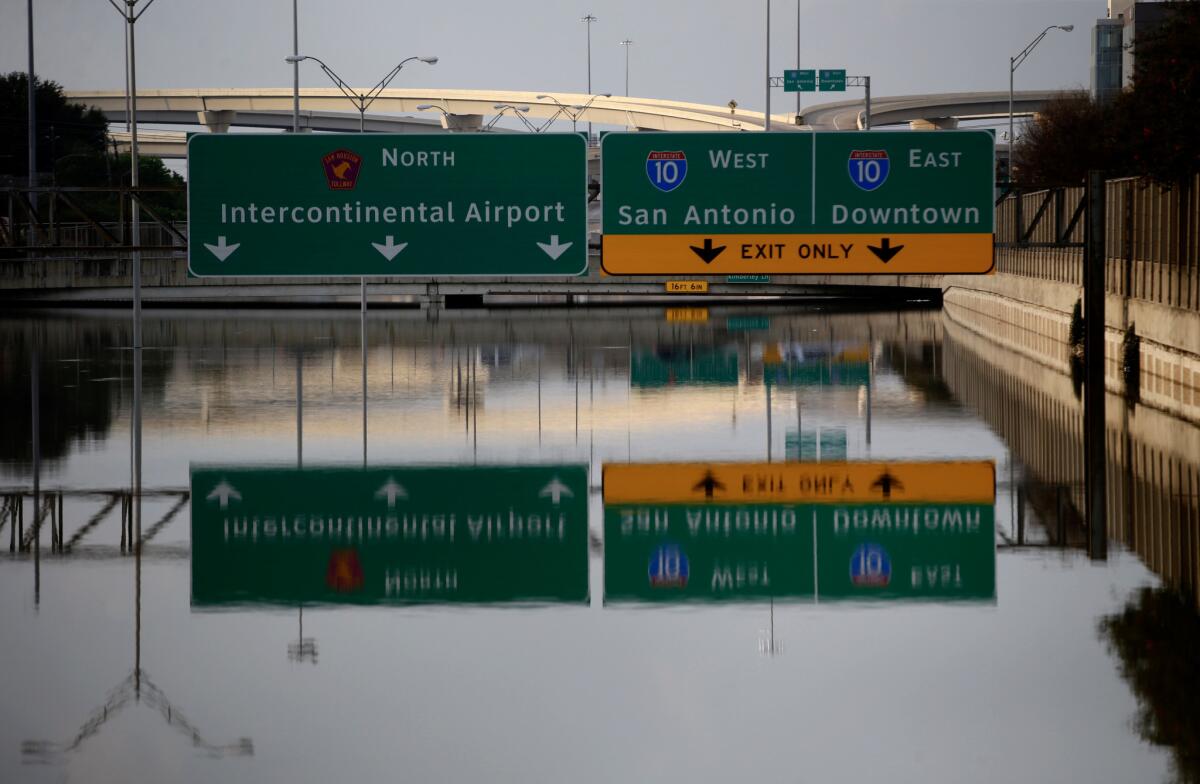

In much of Houston, the floodwaters have receded, allowing traffic to flow on the city’s freeways, where there had been dramatic scenes of white-capped waves only days before.

But cities and towns to the east remained underwater. In Beaumont, where the population is about 118,000, Saturday marked the third day residents went without clean water after flooding overwhelmed the city’s pump system.

Throughout the state, relief workers and volunteers continued to survey the wreckage of homes and neighborhoods, searching for survivors or those who died. According to the Houston Chronicle, more than 50 people are thought to have lost their lives to the storm.

During his second visit to the region this week, an upbeat Trump, with First Lady Melania Trump, toured a hurricane relief center in Houston, where he handed boxes of food to evacuees and sought to reassure residents that his administration was engaged in Texas’ recovery efforts. Declaring himself “very happy” with the efforts underway, he told reporters, “It’s been really nice. It’s been a wonderful thing. As tough as this was, it’s been a wonderful thing. I think even for the country to watch it, for the world to watch. It’s been beautiful.”

“It’s going so well that it’s going fast, in a certain sense,” he said of the response to the storm, adding that while the process of rebuilding might take some states years, “because this is Texas, you’ll probably do it in six months.”

The president’s second post-hurricane trip, which included a stop in southeast Louisiana, came after criticism that he didn’t meet with victims of the storm during his visit Tuesday to Corpus Christi. Trump said that was intentional because he did not want to interfere with rescue and recovery operations.

“We’re signing a lot of documents now to get money,” he said, a reference to the White House’s request to Congress on Friday for $7.9 billion in immediate aid. Officials said this was only a down payment, a portion of a much larger funding request that could exceed $100 billion.

Trump’s visits and comments in the wake of Harvey have been notable for how little attention they’ve gotten from Texans.

In the presence of reporters over the past week, Trump’s name has been spoken little, if at all, inside the distressed neighborhoods stretching from wind-slammed Rockport in south Texas to flood-drenched Port Arthur in east Texas.

The same has been true of any other outsider not trapped inside the storm’s tumultuous world, for that matter. In the places with running televisions, the screens have been glued to storm coverage, not politics. They show news conferences from Texas county judges rather than national congressional leaders; viewers hear from little-known meteorologists and hydrologists rather than panels of famous political journalists.

In a year when it seems like all politics has been all-Trump, the flooded communities in Texas have shown how intensely local disaster politics can be.

Take the subdivision of Millwood in unincorporated Fort Bend County, for example. In the well-to-do neighborhoods in nearby Sienna Plantation, the floodwaters from heavy rains have dropped, leaving behind a layer of brown muck on the roads but otherwise allowing owners to return to their homes to begin cleanup.

But in Millwood, water was still pooled in the streets Saturday, preventing trucks from entering. To get inside, residents hauled ladders and boxes down an elevated earthen levee running along a nearby canal so that they could climb the brick walls behind their homes and get in.

Inside Amar Gowda’s upscale brick-and-stone home, which had about a foot of water, men in white hazardous materials suits and masks stripped soggy hardwood planks from the floor, tossing them into a pile with a clatter.

To Gowda, a 33-year-old software architect, the historic hurricane may have been an act of God, but the flooding in his neighborhood was not. When he bought the home, he said he was told he was not in a flood zone, and so he doesn’t have federal flood insurance to cover the losses.

He blamed “poor planning” by the subdivision’s developers, and blamed local officials for not bringing in more water pumps sooner. Now he and his neighbors are considering a class-action lawsuit.

Asked about Trump, neighbor Jay Parekh, 40, replied, “We are not interested in what he’s doing right now. Nobody here has flood insurance.”

One of the neighbors who does have flood insurance was Judy Wong, a 66-year-old retiree. When she briefly got emotional during an interview, it wasn’t when she spoke about Trump, but about her homeowners’ association.

“I feel like they’ve done everything they can,” Wong said of Trump and the federal government. But in her neighborhood, she said, “The pumps were not adequate.”

Sitting outside the neighborhood, at guard, was a Fort Bend County deputy who said he’d been working more 100 hours straight. “Let’s get them out first, and then litigate,” he said.

Up in western Houston, along the Buffalo Bayou, residents’ lives have been shaped most dramatically not by Trump but by flood-control infrastructure and federal agencies whose emergency response programs long predate the president.

Two dams upstream from the bayou were filled to the brims with rains from Harvey. To protect the dams from failing and possibly destroying more neighborhoods, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has started steady releases that have flooded some homes along the bayou.

“Thirty years, we’ve never had anything back there,” said Olga Cortez Bullock, 76, sitting in a chair in the shade in a neighborhood along the bayou as she waited for men she’d hired to bring back some of her belongings on a boat. Her house and home office had been flooded with 2 feet of water.

The water from the rains “had just gotten up to the last step and it stopped,” Cortez Bullock said. Then the dams began spewing water into the bayou, flooding her home and three cars. “I’m not happy about that release,” she said.

And asked about Trump’s visit, Cortez Bullock instead wanted to know when his Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Small Business Administration would begin processing recovery claims so she could get back to work running a watch and jewelry convention.

“In the meantime, small businesses suffer,” Cortez Bullock said. “A lot of people are hired by small businesses, so what are they supposed to do? .... People are not going to come into your house to fix it if they’re not sure they’ll get paid.”

A couple blocks over, Ronnie Wathough, 58, waited at the edge of the water for his son-in-law, who was on a boat, to fetch some belongings from Wathough’s flooded home. Wathough, too, had criticism for flood-control officials. “I understand why they opened it,” Wathough said. “I understand why they did what they did. I think they did it too late.”

Asked about the president, Wathough was indifferent. “I don’t care if you’re the president, the pope, the king,” Wathough said. “There’s nothing you can say to make these people feel better.”

Amid the signs of gradual progress came warnings of the difficulties ahead.

Houston city officials alerted residents on Saturday that scammers claiming to work for insurance companies were calling flood victims and claiming they had to pay overdue premiums or they would lose their insurance. And in a statement issued jointly with the FEMA, the city warned of disturbing reports of people impersonating emergency response officials in order to enter victims’ homes.

Officials with the Houston Independent School District, the fourth-largest in the country, reported that after surveying most of the district’s nearly 300 schools, only 115 had so far been deemed safe to open by the target date of Sept. 11. By that time, officials hope that about 218,000 students will be able to return to school.

About 75 schools sustained “major” or “extensive” damage, and the district expects to have to relocate 10,000 to 12,000 students.

The Houston Astros were scheduled to play their first home game since the storm, returning Saturday for a doubleheader against the New York Mets at Minute Maid Park, less than half a mile from the evacuation site at the George R. Brown Convention Center. The team announced it would provide 5,000 tickets to each game to volunteers, first responders and evacuees.

Inside Minute Maid Park, the Jumbotron above right field read: “Houston strong” in blue, orange and white. “Dedicated to all those who lost their lives, property and were affected by the flood,” it said.

“Strong” seems to have become the rallying cry of disasters. It echoed “Boston strong,” the ubiquitous slogan that emerged after the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

Times staff writers Pearce and Branson-Potts reported from Houston and Phillips from Los Angeles. Staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske contributed from Houston.

Times staff writer Katherine Skiba in Washington contributed to this report.

Twitter: @mattdpearce

Twitter: @haileybranson

Twitter: @annamphillips

ALSO

After the search and rescue ends, what comes next for Harvey victims?

‘I think he’s barbecuing’: A helicopter view of the Texas flood with the California National Guard

After Harvey, Texas rallies to rescue cats and dogs, with lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina

UPDATES:

6:40 p.m.: This article was updated throughout with additional reporting, including reaction to Trump’s visit and comments from flood survivors.

12:50 p.m.: This article was updated to include comments by President Trump praising rescue and recovery efforts.

12:05 p.m.: This article was updated to include comments by President Trump after meeting with flood victims and handing out food and supplies.

9:30 a.m.: This article was updated with Trump’s arrival in Houston and details about Texans who remain without power or clean water.

This article was originally published at 8:05 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.