At Standing Rock, the nation’s most famous environmental protest, not just any toilet will do

- Share via

Reporting from Along the Cannonball River, N.D. — The scale and duration of the protests that have unfolded here over the fall and winter by those determined to block the Dakota Access oil pipeline have created endless logistical challenges.

The camps are far from any city, lack electricity and running water and offer no permanent shelters. If people need something, they have to bring it or build it. That includes bathrooms.

For many months, the prairie grass provided the only accommodations. Then, in a sign that protesters planned to stay awhile, portable toilets were hauled in.

Late last fall, though, a new problem arose: The weather started getting cold. Soon it would get really cold, North Dakota cold, as in well below zero. At those temperatures, the contents and occupants of portable toilets can freeze.

And so it was that one of the nation’s largest and longest environmental protests found a solution to an environmental problem that had nothing to do with the fight against fossil fuels. They needed to go to the bathroom, so they created an elaborate composting toilet operation that has become a marvel of efficiency and an unlikely center of community.

“Everyone’s happy and relaxed in here,” said a woman from Burbank who goes by the name Dancing Fox and is one of scores of volunteers who help maintain the toilets. “You’ve got hand sanitizers, baby wipes, news bulletins, joking, singing, party lights.”

She was not kidding. People milled about, chatting, checking fliers posted on a wall. The place is warm and lively — and not particularly malodorous.

“It’s minty,” Dancing Fox said, perhaps embellishing.

The idea for the toilets came about in November, when a protester suggested to Chief Dave Archambault of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe that he invite global nonprofit GiveLove.org to help create a composting bathroom system to handle the hundreds of protesters who flocked in to help the tribe in its fight against the pipeline.

GiveLove, formed by actress Patricia Arquette in response to the 2010 Haitian earthquake, has created composting toilet systems there and in Colombia, Uganda, Kenya, India and elsewhere. But the upper Great Plains presented a new frontier.

“It was a huge challenge to get it up and running in a blizzard,” said Alisa Keesey, the organization’s program director.

GiveLove staff spent weeks at the camp, building the wooden boxes that serve as toilets, working with others to design and build the spaces and to organize volunteers who would manage the new facility. Arquette herself spent considerable time there, helping build more than 100 of the commodes, Keesey said.

By early December, with temperatures plummeting and snow piling up, three toilet operations were opened in large old Army tents. Each includes 13 toilet stalls surrounding a common area with a wood-burning stove that ventilates through ducting in the fabric roof. Wood framing around the sides of the tent is lined with hay for insulation.

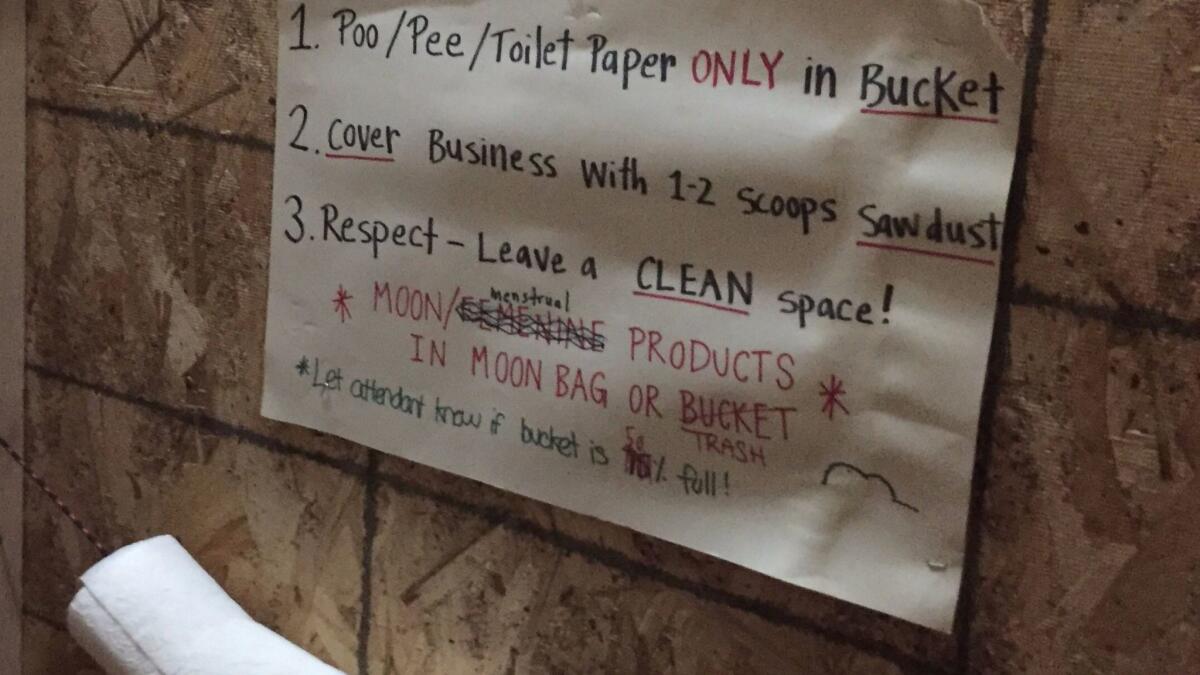

Odor control consists of pine shavings every user is instructed to spread over their business. People also burn sage, and the aroma of the wood stove helps as well.

One of the volunteers on a recent weekday was a woman from Montana who goes by the name Peaches and said she is a nurse. Peaches said that the camp, which has swelled into the thousands at times but recently had dwindled to a few hundred people, has had no notable outbreak of intestinal viruses despite the lack of plumbing and the close quarters people have kept, particularly during the winter.

“We seem to be making up for it with magic,” Peaches said. “These sorts of situations without running water, without sewage, do tend to lead to spreads of disease. We’ve had some upper respiratory flu, but it’s usually G.I. stuff that you get in these sorts of situations, and that’s not happening.”

The composting process begins at the toilet. The wooden toilet boxes are lined with a green compostable bag, which is surrounded by a white plastic bag. When the wooden boxes become half full, which can happen several times a day, a volunteer uses the plastic bag to remove the compostable bag. The compostable bags are then moved to a shipping container staged on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

The actual composting will not begin until the weather begins to thaw. Volunteers will build large compost bins and cover the contents of the toilets with rotted hay or straw.

Not all of the camps at Standing Rock are using the composting toilets. The original camp, Sacred Stone, which was established on a bluff above where the larger camp later formed, still uses pit latrines. Some protesters, particularly elderly ones, have been given composting toilets to use at their individual campsites.

There is pressure now for people in the larger camp, called Oceti Sakowin, to move. The Standing Rock Sioux tribe is urging people to clear out in advance of anticipated spring floods and to help improve relations with local government and law enforcement — especially since the Trump administration has approved the last permit for the pipeline, and the fight is now moving toward the courtroom.

Keesey said the composting toilets can be moved, perhaps to protest camps elsewhere. Some Native American tribes have expressed interest in using composting toilets on rural reservations that lack plumbing.

Who knows the possibilities, Keesey said. “This is kind of the next new thing.”

ALSO

Waning days of the Standing Rock protests: An improvised tribe of Americans looking for ‘justice!’

Raids across the U.S. leave immigrant communities and activists on high alert

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.