Santa Fe, unlike Parkland, says the issue behind the latest school shooting isn’t guns

Hundreds gather for a May 18 vigil honoring victims of the Santa Fe High School shooting in Texas.

- Share via

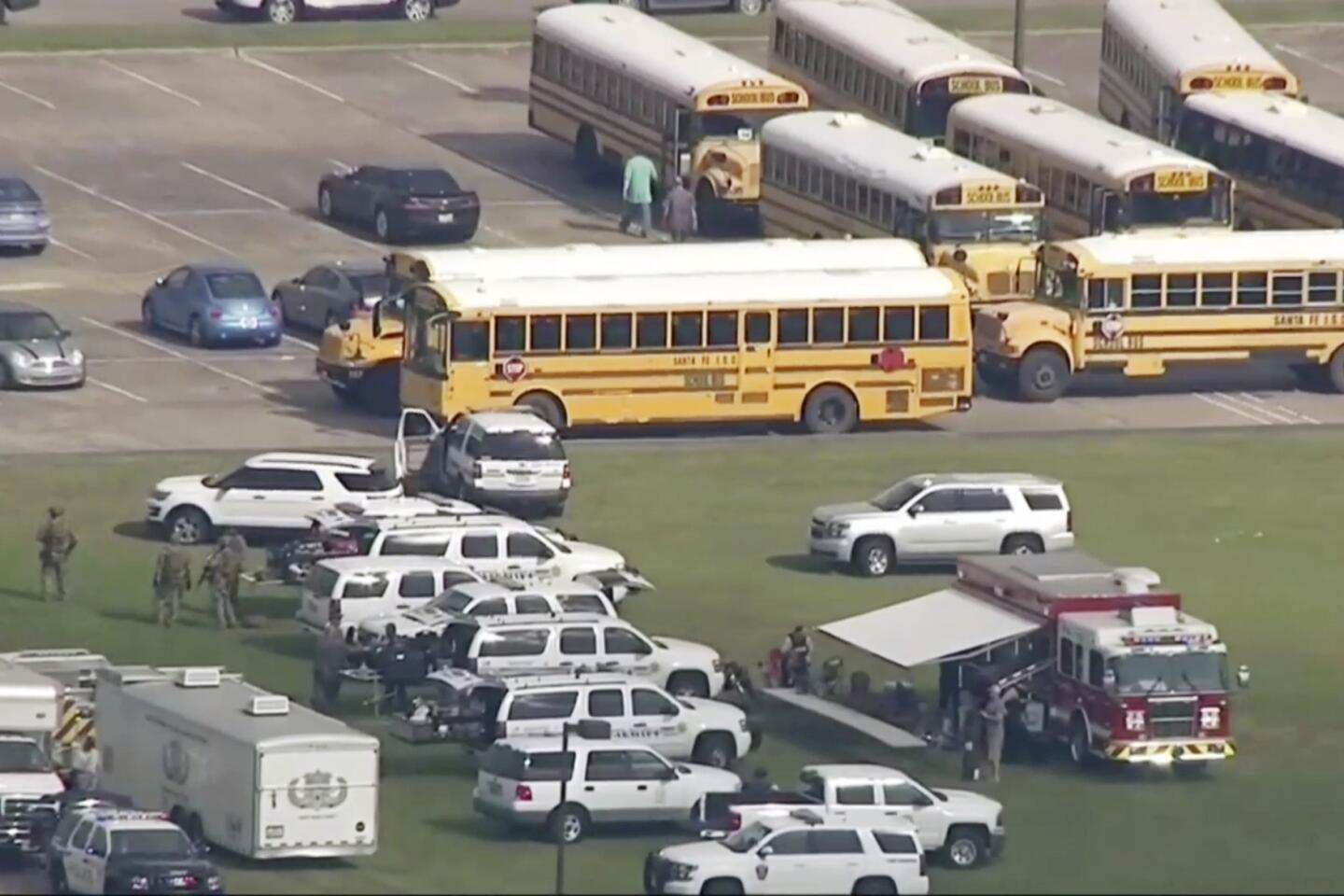

Reporting from SANTA FE, TEXAS — Students and teachers returning to Santa Fe High School on Saturday to claim belongings left behind during the evacuation had to be escorted by police: The school was still a crime scene, cordoned off with yellow police tape.

They were joined by Cassandra Garza, a sophomore. She didn’t bring a sign with a political slogan, or talk about gun control. All she wanted was to be with her friends, Cassandra said, and “to get together and pray this never happens again.”

“I’m young and naïve about politics,” the 16-year-old said.

There was no outcry against firearms in Santa Fe after a gunman killed 10 and wounded 13 others Friday. Guns didn’t come up at a prayerful vigil attended by 1,000 people that evening. On Saturday, there were no protests, and local leaders don’t expect any Sunday.

But three months earlier in Parkland, Fla., the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School that left 17 dead unleashed a movement, with students and parents of the dead organizing, protesting and calling for expanded gun control laws. Their activism led to school walkouts nationwide, voter registration drives and massive demonstrations, including the March for Our Lives in Washington.

Polls show the U.S. remains deeply divided about guns, and the responses in Parkland and Santa Fe help explain why.

Residents in both cities say something needs to be done about school shootings, but there’s no agreement on what that something should be.

Outside the high school Saturday, Sandy Phillips said she was not surprised to be the lone advocate there for gun control.

Phillips, a San Antonio native, was wearing a pin with a photo of her daughter, Jessica Ghawi, who was killed in the mass shooting in Aurora, Colo., six years ago at age 24. Phillips and her husband have since responded to support fellow victims at the scenes of nine other mass shootings. She also protested outside the National Rifle Assn. convention in Dallas earlier this month.

“It’s unfortunate they’ve already made up their minds about what happened here. They’re gone right to, ‘No one’s taking my guns.’ The typical NRA rhetoric. It’s all about ‘pray,’” Phillips said.

She sees little chance for a meeting of minds about guns.

“People go their own ways,” she said. “It divides the community, divides the students.”

The Rev. Brad Drake has ministered to the Santa Fe community for seven years at Dayspring Church, an Assemblies of God congregation of about 150 people a few miles from the high school. The town of about 13,000 has 15 churches, and Drake serves on the local ministerial alliance as well as the Chamber of Commerce.

After the shooting, he worried that outside groups might show up with political agendas. He noticed a man openly carrying a handgun on his hip at the Friday vigil. But that was it, he said.

“We’re able to look past that stuff and just take care of people,” Drake said as he sat in his office.

Drake, 45, is a gun owner, with a deer head mounted on his office wall. He’s also a father of five who lost a member of his congregation in the shooting, student Angelique Ramirez. On Friday, he was waiting nearby as officials notified her parents and the parents of seven other victims.

“You could hear it down the hallway as each family reacted,” he recalled.

Like many in Santa Fe, the pastor didn’t fault guns. He faulted himself, and society. Schools need help to improve security, but that won’t prevent shootings, he said. Neither will prayer alone, he added.

“We have created a culture that does not value life, that does not honor God, that does not respect authority. We are reaping the consequences of those actions, and that’s not going to be reversed by a security guard or a metal detector,” he said.

You’re not hearing a lot about gun control.

— Richard Pourchot, youth minister

Youth minister Richard Pourchot accompanied Angelique’s parents when they were notified of her death. He saw them break down, and spent the evening with them afterward.

“You’re not hearing a lot about gun control,” he said, and while he said school security should be stepped up in the short term, “the long-term goal is to change hearts.”

“We’re allowing the culture to raise our kids,” added Pourchot, a father of two who graduated from Santa Fe High in 2000.

On Saturday, Pourchot and Drake opened the church sanctuary for their response to the shooting: public prayer. Drake wondered aloud how long the shooting would stay in the limelight.

“Do people really care, or do they just want to push an agenda?” he said.

No local officials mentioned guns at an afternoon briefing outside the high school.

Asked about gun control, Galveston County Judge Mark Henry said expanding laws wouldn’t prevent mass shootings.

“I can’t speak for our entire country, but we need to pay more attention to mental health,” Henry said, saying tougher gun laws won’t keep firearms out of the hands of criminals because “they won’t abide any.”

A few yards away, Clarissa Potts and her 7-year-old daughter, Kaylee, added flowers to a growing memorial under a tree outside the school. She, too, opposes expanding gun control laws. She said parents need to get more involved with their children.

“We need better communication. We need to pay more attention to mental health. I don’t think it’s a gun control issue. It’s their constitutional right to carry guns,” said Potts, 41, who does not own guns.

Up the street, a Santa Fe High junior who stopped at the Shell gas station that sells “Hunter for life” caps said she agreed.

“It’s not the guns; it’s the people,” said Dawn Pence, 17, who wore cowboy boots and a Def Leppard T-shirt. She wasn’t at the school Friday, and didn’t know the alleged shooter or any of the victims.

A few local officials, students and victims’ families did blame guns for the shooting and called for increased gun control Saturday. But they kept a low profile, contacting Parkland student activists for advice and speaking out virtually, on social media.

Rhonda Hart posted her plea on Facebook after learning her daughter Kimberly Vaughan was among the dead: “Call your congressmen. We need GUN CONTROL. WE NEED TO PROTECT OUR KIDS.”

Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo expressed frustration with officials who “ran to the cameras today, acted in a solemn manner, called for prayers, and will once again do absolutely nothing.”

“Please do not post anything about guns aren’t the problem and there’s little we can do,” Acevedo wrote on Facebook. “…The hatred being spewed in our country and the new norms we, so-called people of faith are accepting, is as much to blame for so much of the violence in our once pragmatic Nation.”

A dozen Santa Fe students who participated in a national walkout last month for expanded gun control posted online after Friday’s shooting and could become active in the coming days, said Matt Deitsch, a Parkland student organizer.

“Some students will speak out. Others will need to find their voice,” Deitsch said in a Saturday text. “We all need to demand change. I feel awful that these students are in the same ugly club.”

Marcel McClinton, co-director of the Houston March for Our Lives chapter, tried to contact students after the shooting, driving to town for a Friday vigil. The 16-year-old left his March for Our Lives T-shirt at home and kept a low profile, offering hugs and support.

“We’re here to help you guys,” he’d say. “You’re not buying into our agenda.”

Marcel survived a mass shooting at his Houston Sunday school two years ago. He’s tried prayer and forgiveness, but still has headaches and flashbacks after other mass shootings.

“I care about kids and having to see kids in fear,” he said by phone Saturday. “The grieving process starts, but it hardly ever ends.”

Marcel spent Saturday conferring with members of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, a Washington-based gun control advocacy group, who had flown in to help reach out in Santa Fe.

“I would be very shocked if at least one student does not want to talk to us to amplify their voice. So we’re waiting,” he said.

Among those drawn to Santa Fe by the shooting was Jason Rogers, a self-described moderate Democrat and community college teacher campaigning for the Legislature farther east.

Rogers, a veteran and gun owner who favors expanded background checks, said he recently joined the American Legion and was assisting with the group’s raffle for a semiautomatic rifle Friday when he heard about the shooting.

Instead of continuing, he came to Santa Fe to talk to people, but says he found that “they don’t really want outside help.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.