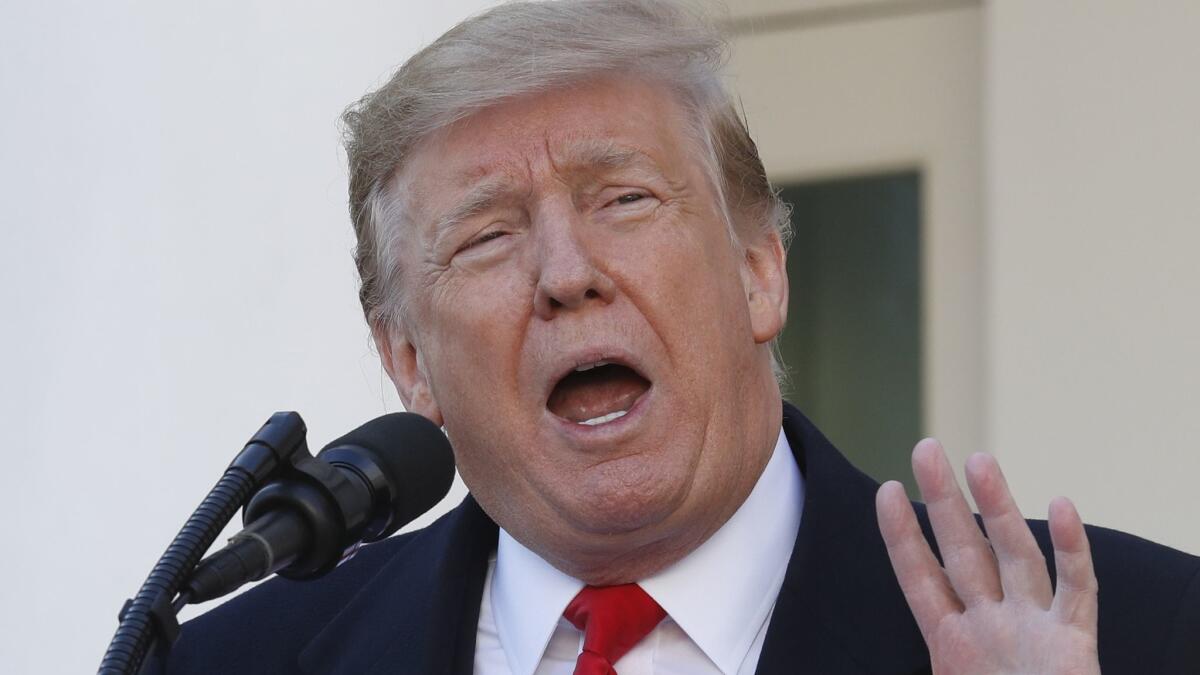

While Trump’s border wall demand shut down the government, his company fired undocumented workers

- Share via

Reporting from OSSINING, N.Y. — They had spent years on the staff of Donald Trump’s golf club, winning employee-of-the-month awards and receiving glowing letters of recommendation.

Some were trusted enough to hold the keys to Eric Trump’s weekend home. They were experienced enough to know that when Donald Trump ordered chicken wings, they were to serve him two orders on one plate.

But on Jan. 18, about a dozen employees at Trump National Golf Club in Westchester County, N.Y., were summoned one by one to talk with a human resources executive from Trump headquarters.

During the meetings, they were fired because they are undocumented immigrants, according to interviews with the workers and their attorney. The fired workers are from Latin America.

The sudden firings — which were previously unreported — follow last year’s revelations of undocumented labor at a Trump club in New Jersey, where employees were subsequently dismissed. The firings show Trump’s business was relying on undocumented workers even as the president demanded a border wall to keep out such immigrants.

Trump’s demand for border wall funding led to the government shutdown that ended Friday after nearly 35 days.

In Westchester County, workers were told Trump’s company had just audited their immigration documents — the ones they had submitted years earlier — and found them to be fake.

“Unfortunately, this means the club must end its employment relationship with you today,” the Trump executive said, according to a recording that one worker made of her firing.

“I started to cry,” said Gabriel Sedano, a former maintenance worker from Mexico who was among those fired. He had worked at the club since 2005. “I told them they needed to consider us. I had worked almost 15 years for them in this club, and I’d given the best of myself to this job.”

“I’d never done anything wrong, only work and work,” he added. “They said they didn’t have any comments to make.”

The mass firings at the New York golf club — which workers said eliminated about half of the club’s wintertime staff — follow a story in the New York Times last year that featured an undocumented worker at another Trump club in Bedminster, N.J. After that story, Trump’s company fired undocumented workers at the Bedminster club, according to former workers there.

President Trump still owns his businesses, which include 16 golf courses and 11 hotels around the world. He has given day-to-day control of the businesses to his sons, Donald Trump Jr. and Eric Trump.

In an emailed statement, Eric Trump said, “We are making a broad effort to identify any employee who has given false and fraudulent documents to unlawfully gain employment. Where identified, any individual will be terminated immediately.”

He added that it is one of the reasons “my father is fighting so hard for immigration reform. The system is broken.”

Eric Trump did not respond to specific questions about how many undocumented workers had been fired at other Trump properties and whether the company had, in the past, made similar audits of its employees’ immigration paperwork. He also did not answer whether executives had previously been aware that they employed undocumented workers.

This Trump golf club does not appear in the government’s list of participants in the E-Verify system, which allows employers to confirm their employees are in the country legally. Eric Trump did not answer a question about whether the club would join the system.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment Friday.

The firings highlight a stark tension between Trump’s public stance on immigration and the private conduct of Trump’s business.

In public, Trump has argued that undocumented immigrants have harmed American workers by driving down wages. That was part of why Trump demanded a border wall and contemplated declaring a national emergency to get it.

Fact check: Do immigrants really hurt wages for American-born workers? »

But, in Westchester County, Trump seems to have benefited from the same dynamic he denounces. His undocumented workers said they provided Trump with cheap labor. In return, they got steady work and few questions.

“They said absolutely nothing. They never said, ‘Your Social Security number is bad’ or ‘Something is wrong,’ ” said Margarita Cruz, a housekeeping employee from Mexico who was fired after eight years at the club. “Nothing. Nothing. Until right now.”

In June 2016, Trump gave a campaign speech at the Westchester club and recounted how he had hugged mothers and fathers whose children had been murdered by illegal immigrants.

“On immigration policy, ‘America First’ means protecting the jobs, wages and security of American workers, whether first or 10th generation,” Trump said in his speech. “No matter who you are, we’re going to protect your job because, let me tell you, our jobs are being stripped from our country like we’re babies.”

To document the firings at the golf course, the Washington Post spoke with 16 current and former workers at the course — which sits among ritzy homes in Briarcliff Manor, N.Y., 27 miles north of Manhattan. Post reporters met with former employees for hours of interviews in a cramped apartment in Ossining, N.Y., a hardscrabble town next door, whose chief landmark is the Sing Sing state prison.

Among those workers, six said they had been fired Jan. 18. They and their attorney confirmed the other terminations.

Another worker said he was still employed at the club at the time of the purge despite the fact that his papers were fake. His reprieve did not last long, however. His attorney later said he was fired that night.

The workers brought pay stubs and employee awards and uniforms to back up their claims. They said they were going public because they felt discarded: After working so long for Trump’s company, they said they were fired with no warning and no severance.

“Keep us in mind,” Cruz said, addressing Trump and the country.

The interviews were organized by an attorney, Anibal Romero, who is also representing undocumented workers from Trump’s club in Bedminster.

The Trump Organization has shown “a pattern and practice of hiring undocumented immigrants, not only in New Jersey, but also in New York,” Romero said. “We are demanding a full and thorough investigation from federal authorities.”

The workers were largely from Mexico, with a few from other countries. Most said they crossed the United States’ southern border on foot and purchased fake immigration documents later. Many bought theirs in Queens, N.Y.

They said Trump Organization bosses did not seem to scrutinize these documents when they were hired.

Edmundo Morocho, an Ecuadoran maintenance worker, said he was hired around 2000 with a green card and Social Security card that he said he purchased in Queens for about $50. The green card he showed the Post says it expired in 2002, but a decade passed before the Trump club told him that he needed to replace it, he said.

Morocho bought a new card, he said. It had a different birth date than the first one, but he said the Trump club didn’t raise questions. The Post viewed both cards. It was unclear whether they were forged or stolen.

“The accountant took copies and said, ‘OK, it’s fine,’ ” Morocho said. “He didn’t say anything more.” Eric Trump did not respond to a question asking about the club’s process for reviewing employees’ immigration documents.

Another employee — Jesus Lira, a banquet chef from Mexico — said that, on two occasions in 2008, an accountant at the Trump club rejected his fake documents and told him to go obtain better ones.

“She said, ‘I can’t accept this, go back and tell them to do a better job,’ ” Lira recalled. He said he returned to Queens a third time and found documents that the club accepted. Eric Trump did not respond to a question about Lira’s account.

The Post spoke to two former managers from the club about the employees’ accounts. One former manager, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the club’s internal practices, said the club relied on its accounting department to scrutinize the immigration documents and that the department rejected about 20% of applicants because of immigration questions.

The other former manager said the broader Trump Organization placed far more emphasis on finding cheap labor than it placed on rooting out undocumented workers. The former manager characterized the attitude at the club as “don’t ask, don’t tell.”

“It didn’t matter. They didn’t care [about immigration status],’ ” said the former manager, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to preserve ties with current Trump executives. “It was, ‘Get the cheapest labor possible.’ ” The former manager said the assumption at the club was that immigration authorities were not likely to target golf clubs for mass raids.

At the club, undocumented workers said they resented the unspoken understanding that they would never be promoted to management. But many had fond memories of interactions with Trump family members, who visited the club for parties and weekends.

Sedano, the maintenance worker from Mexico, said he had a set of keys for a home that Eric Trump used at the course, because Sedano was responsible for taking out the trash there and making repairs.

Sedano recalled cleaning the railings one day at the club’s main entrance when Donald Trump approached him.

“He asked me how long I had worked there. At that time, it had been about five years,” Sedano recalled.

Trump noticed Sedano’s wedding ring. He handed Sedano $200.

“He said, ‘Take your wife out to dinner,’ ” Sedano said. “I’ll never forget that.”

Alejandro Juarez, a native of Mexico who had worked as a server and food runner at the club since 2007, said Eric Trump greeted him by name at a party in December.

“I was serving hors d’oeuvres,” Juarez recalled, “and he told me, ‘Thanks, Alejandro. Thanks for everything, OK?’”

This month, Sedano and Juarez were among those fired. Sedano’s wife, a housekeeper at the Trump club, said she was fired on the same day.

The firings began about 10 a.m.

Cruz, the fired housekeeper, knew what was coming before she went in, because she’d heard from other workers who’d already been fired. She felt like the workers were sitting there “like little lambs, lined up for the slaughterhouse.” She hit the “record” button on her phone before her firing began.

Deirdre Rosen — an executive who identified herself as the head of human resources for the Trump Organization — began by reading from papers in front of her, Cruz said. An interpreter, listening in on speakerphone, translated her words into Spanish.

He translated Rosen’s statement that, after a Trump Organization audit, the paperwork Cruz submitted in 2011 “does not appear to be genuine.”

Then he translated Rosen’s question: “Are you currently authorized for employment in the United States?”

“Um, no,” Cruz replied.

“No,” the man on the phone translated.

Rosen continued: “By law, the club cannot continue to employ an individual knowing that the individual is, or has become, unauthorized for employment,” Rosen told her. “Unfortunately, this means the club must end its employment relationship with you today.”

Cruz told them she was a single mother with two children and asked why she had not been given some warning, so she could look for another job.

“The law says as soon as we know that you do not have authorization that we cannot continue your employment. That’s why,” Rosen said. As Cruz left, Rosen said, “Have a great day.”

Rosen could not be reached for comment.

Afterward, Cruz said she felt that — from one instant to the next — the Trump Organization had sought to transform her from an employee to a nonentity.

“We’re just working. How can they take our taxes, charge us for this or that, and not give us any rights?” Cruz said. “When they take our taxes, we count as people. Why don’t we count in other things?”

She said, “We don’t exist.”

Joshua Partlow and David A. Fahrenthold write for the Washington Post. Alice Crites, Tom Hamburger and Philip Bump of the Post contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.