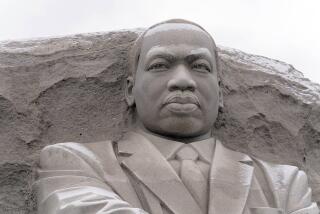

Pledging to carry on his mission, thousands mark 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death

Thousands in Memphis, Tenn. mark the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death.

Reporting from MEMPHIS, Tenn. — For Cleophus Smith, who has labored as a sanitation worker in Memphis for half a century, it was important to mark the 50th anniversary of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s death by marching a mile and a half in his honor.

Dressed nattily in a tweed jacket, blue tie and polished brown leather shoes, the 75-year-old Smith scoffed at those who urged him to ride in a golf cart.

“I am thinking of the legacy Dr. King left for us to carry on,” Smith said as he joined the crowd that filled downtown Memphis. “We’re determined to carry it forward.”

That theme — of carrying on King’s work — was sounded at events across the country Wednesday, as thousands assembled to recall his death, celebrate his life and rekindle his struggle for economic and social justice.

In an echo of King’s visit to Memphis in 1968, scores of men on Wednesday carried black-and-white signs identical to ones carried that year by striking sanitation workers: “I AM A MAN.”

Many who rallied outside the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local Union 1733 headquarters on Beale Street early Wednesday were sanitation workers whose strike for better working conditions inspired King to come to Memphis.

King was fatally wounded on April 4, 1968, as he stood on a balcony of the Lorraine Motel, which is now part of the National Civil Rights Museum. Jesse Jackson, the 76-year-old civil rights activist who is one of the last living witnesses of King’s assassination, stood on the balcony Wednesday.

“The balcony does not have the last word,” he said. “We would not let one bullet kill a movement.”

At the King Center in Atlanta, Bernice King, the slain civil rights leader’s youngest daughter, said, “Now more than ever before, we need his teachings, his principles, his steps of nonviolence.”

The King Center presented its highest award, the Martin Luther King Jr. Peace Prize, to social activist and lawyer Bryan Stevenson and Benjamin Ferencz, a prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials of Nazis after World War II.

PHOTOS: A nation remembers Martin Luther King Jr. »

Among those who remembered King on Wednesday was Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), who spoke in Indianapolis, where Sen. Robert F. Kennedy announced news of King’s death during a presidential campaign rally. “I have bad news for you, for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and killed tonight,” Kennedy told the crowd that evening.

“I cried,” Lewis said. “I lost a friend. I lost a great brother. I lost my leader.”

Lewis, addressing a crowd at the Landmark for Peace Memorial in Martin Luther King Jr. Park, added: “If it hadn’t been for Martin Luther King Jr., I don’t know what would have happened to our nation.”

RELATED: How MLK’s death affected a nation, as told by those who remember it »

President Trump, in a video posted on Twitter, celebrated King’s legacy. “We rededicate ourselves to a glorious future where every American, from every walk of life, can live free from fear, liberated from hatred, and uplifted by boundless love for their fellow citizens,” Trump said.

And while some celebrated the advances in civil rights over the last half-century, many said King’s work remained unfinished. At a silent march in Washington, participants wore green “Act to End Racism” shirts.

In Memphis, some who gathered Wednesday outside the Lorraine Motel clutched brown cardboard signs that said “#ThingsAreNotOkay.”

“He died fighting, but everything is still the same,” said Edith Ornelas, 32, an arts advocacy educator who moved to Memphis from Chicago a year and a half ago. “So many people celebrate his legacy but ignore what’s happening around them. We have poverty and homelessness, and immigration is the new slavery.”

The leaders of a parade of civil rights groups, such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Poor People’s Campaign, were cheered as they spoke of the challenges that continue to afflict poor and black Americans: low wages, rising rents, healthcare costs and the suppression of voting rights.

The words of some elected officials, including Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland and Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam, were drowned out by boos and chants.

“50 years!” a small huddle of young protesters chanted. “No change!”

For the sanitation workers, the rally and march in Memphis were a way to repay their debt to King.

“If it weren’t for King, we’d still be on strike,” said Elmore Nickleberry, who at age 86 is the city’s longest-serving employee. After hauling garbage downtown for more than 60 years, he still drives a truck for the sanitation department.

RELATED: 1968: A timeline of anger, grief and change »

More than 1,300 Memphis sanitation workers went on strike in February 1968 after two garbage collectors, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a truck’s malfunctioning compactor. Frustrated by years of shoddy treatment, black workers demanded better pay and benefits and safer working conditions.

King, who had just launched the Poor People’s Campaign, tried to lead a peaceful march in Memphis on March 28, but it turned violent as a small group of protesters broke windows. In response, police wielded mace and tear gas.

King returned to Memphis for another march in support of the sanitation workers. The bullet that killed him, fired by segregationist James Earl Ray, hit him in his lower right jaw, entered his neck and fractured his spine. Less than an hour later, he was pronounced dead.

After the Memphis rally, a crowd of thousands of union workers, pastors, civil rights activists and students marched to the Mason Temple Church of God in Christ, where King delivered his final speech — “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” — the night before he was assassinated.

A convoy of golf carts ferried elderly sanitation workers. The crowd chanted, “We are the 99%,” and sang the old civil rights anthem, “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ’Round”:

“I’m gonna keep on walkin’

Keep on talkin’

Marchin’ into freedom land.”

Many in the crowd recalled the shock of King’s assassination, even though they were too young to understand it back then.

“I remember my father coming home and telling mom, ‘They killed King,’” said Curtis McClendon, a 57-year-old street maintenance worker. “I thought they were talking about a real king.”

Marveling at the crowd around him, McClendon added, “I don’t know if I’ll ever attend an event as significant as this in my lifetime.”

Johnnie Mosley, 53, a librarian, said he marched for his father, John C. White, who worked for the city’s sanitation department for more than 50 years and died in 2005. For him, “I AM A MAN” was more than a slogan.

“One of the things my dad taught me was to be happy to be the son of a garbage man,” he said. “It wasn’t popular. People would make jokes about it. But my dad taught me every man had a dignity about himself, whatever his job.”

Many of the sanitation workers who attended the commemorations credited King with the significant improvements in their working conditions.

Fifty years ago, sanitation trucks were not equipped to lift trash bins and residents did not leave garbage at the curb. Sanitation workers had to haul 50-gallon drums through residents’ yards. Trash juice and maggots would fall down their backs. When they finished their shifts, they did not have access to shower facilities.

“It was hard,” Nickleberry said. “We couldn’t ride the bus, we smelled so bad. But I had two kids and a wife, so I had to do it.”

Less than two weeks after King’s death, the Memphis City Council voted to recognize the union and pay higher wages, and the strike was over. Workers, he said, were eventually equipped with better trucks, uniforms, shoes and raincoats.

“That man came to our town and tried to fight for us and help us,” Nickleberry said. “I feel real bad he had to die.”

The march and rally — organized by I AM 2018, a new movement by AFSCME and the Church of God in Christ to mobilize activists to fight for racial and economic justice — is part of a week of activities commemorating King across Memphis. On Tuesday evening, thousands packed the pews of Mason Temple, 50 years after King delivered his last speech from the pulpit.

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life — longevity has its place,” King said that night. “But I’m not concerned about that now…. I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

Andrew Young, the civil rights leader and former Atlanta mayor who was on the balcony with King when the shot rang out, spoke of King’s enduring legacy.

“Africans say, ‘You ain’t dead until the people stop calling your name,’” he said. “That bullet only released his spirit, and it released his spirit all over the world.”

On Wednesday evening, a large crowd gathered at the National Civil Rights Museum and looked up at a bronze church bell on a scaffold. At 6:01 p.m., the moment King was shot, it began tolling 39 times — one for each year of King’s life.

Then, much as news of his death spread around the world, bells rang out in downtown Memphis, in Washington, in Los Angeles. Even in Vatican City.

As the bell tolled, the museum crowd was quiet. A red and white wreath was fastened to the balcony and Jackson bowed his head, both hands clutching the railing.

Al Green launched into “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” the song King had requested minutes before he was shot. All of a sudden, thousands moved. Friends held hands. Women raised their arms in the air. Almost everyone, it seemed, began to smile and draw together with loved ones.

Jarvie is a special correspondent. Times staff writer Michael Livingston in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

4:45 p.m.: The article was updated to report the tolling of bells in King’s memory.

3:40 p.m.: The article was updated with comments from Jesse Jackson and Bernice King.

1:15 p.m.: The article was updated with additional details on the commemorative events in Memphis, Tenn.

10:45 a.m.: The article was updated with a march in Washington, D.C., and comments from Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) and President Trump.

The article was originally published at 6:55 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.