Hawaii employee who sent alert thought real missile was incoming; state emergency manager resigns

- Share via

Hawaii’s state emergency manager resigned Tuesday after officials said a recent false alarm warning of an incoming missile was triggered by an employee who got confused during an unplanned drill and thought the state was really under attack.

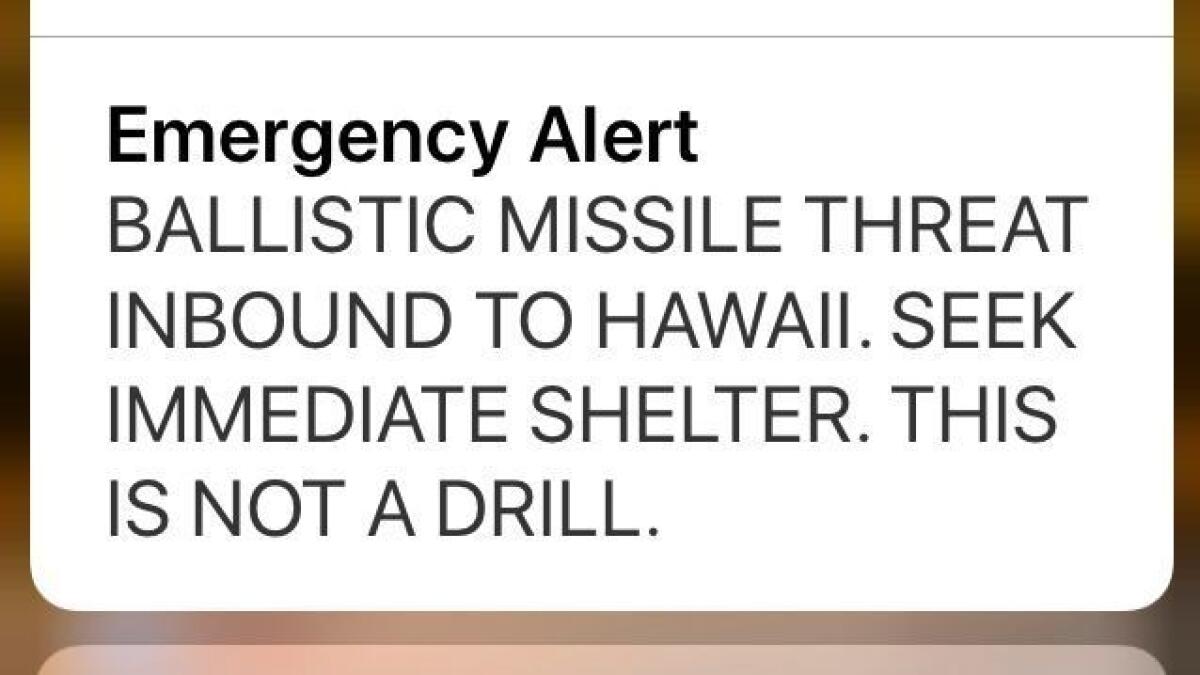

State and federal inquiries into the Jan. 13 incident — in which the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency broadcast a missile-attack warning on residents’ phones, televisions and radios — concluded that the employee did not accidentally click a wrong button on a confusing computer menu, as officials originally said.

Instead, officials said, the unidentified employee had a history of mishaps and apparently did not hear a message that the missile-attack drill was simply a test.

But blame did not fall entirely on the employee. A preliminary investigation by the Federal Communications Commission attributed the false alarm to both “human error and inadequate safeguards,” finding that top emergency management officials miscommunicated with one another about their plans for a drill, leaving it to be done “without sufficient supervision.”

“There were no procedures in place to prevent a single person from mistakenly sending a missile alert to the State of Hawaii,” James Wiley, an advisor to the FCC, said in prepared remarks to the commission Tuesday. “While such an alert addressed a matter of the utmost gravity, there was no requirement in place for a warning officer to double check with a colleague or get signoff from a supervisor before sending such an alert.”

The state official who resigned, Vern Miyagi, oversaw Hawaii’s efforts to prepare its alert system over the last year as North Korea undertook missile tests that suggested the nation could strike the U.S.

An night-shift supervisor at the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency decided to hold a missile drill during the agency’s shift change, in order to see how the agency would respond in a challenging situation.

The supervisor then played a recorded phone call to the agency’s employees, pretending to be U.S. Pacific Command, which would normally warn the agency of a missile attack.

“The recording began by saying ‘exercise, exercise, exercise,’ language that is consistent with the beginning of the script for the drill,” Wiley said. “After that, however, the recording did not follow the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s standard operating procedures for this drill.

“Instead, the recording included language scripted for use in an Emergency Alert System message for an actual live ballistic missile alert. It thus included the sentence ‘this is not a drill.’ The recording ended by saying again, ‘exercise, exercise, exercise.’ ”

The agency’s day-shift warning officer heard “this is not a drill,” but not “exercise, exercise, exercise,” according to the statement the officer provided to state officials, while declining to answer their questions.

The officer then issued the real-life alert to the public from the agency’s alert software, which told Hawaiians that the alert was not a drill.

Within minutes, state, federal and local officials confirmed with one another that the alert was a false alarm, according to the federal report. The public was unaware, however, and many Hawaiians raced for shelter as officials were caught unprepared for how to address a false alarm.

The state emergency agency canceled the alert, but its software did not include an “all-clear” message to the public, leading emergency officials to try to notify the public through other media, including Facebook, Twitter and phone calls to media outlets.

Hawaii’s governor was unable to tweet sooner because he had forgotten his Twitter password.

It ultimately took state officials 38 minutes to issue an all-clear alert the same way it had issued the initial false alarm.

Najm Meshkati, a professor of engineering at USC who studies complex system failures, called the Hawaii false-alarm a “classic” breakdown in which “there is not a very good handover from one shift to another shift and the information falls through the cracks.”

Meshkati urged officials to look beyond the individual’s failure and to “look deeper in the system” for bigger structural problems that led to the false alarm.

State emergency officials have since revised their polices so that surprise drills for employees are prescheduled with their supervisors and that two officers are now required in order to send an alert, not just one. The agency also added the ability to send a false-alarm message immediately.

Matt Pearce is a national reporter for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @mattdpearce.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.