Harambe was the meme we couldn’t escape in 2016

Before Harambe died, he was just a gorilla. Now, he’s meme history.

How did a zoo animal become the centerpiece of ironic Internet culture in 2016? The answer involves Black Lives Matter, celebrity deaths, a popular video game, emojis, and the presidential election.

It started on May 28, when a child fell into the gorilla enclosure at the Cincinnati Zoo. Zoo officials made the difficult decision to shoot and kill the 17-year-old Western lowland silverback gorilla to protect the child.

In the following days, it was as though everyone on the Internet had suddenly become an expert on zoo safety, parenting, and gorilla body language. The thinkpiece machine whirred into action. CNN asked Trump if he would have shot the gorilla (“very tough call,” but yes, he would have).

There was also a massive outpouring of public grief for a gorilla most people in the U.S. probably had never heard of while he was alive. More than half a million people signed a “Justice for Harambe” petition on Change.org. The backlash began: “It’s a gorilla, get over it,” wrote a columnist in the National Post.

At this point, the news cycle should have moved on. But it didn’t. New, non-gorilla-related news stories were turned into Harambe memes. Internet commenters brought up Harambe at every possible opportunity. Harambe was everywhere.

Shontavia Johnson, a law professor and the director of Drake University Law School’s Intellectual Property Law Center, explained that memes behave a lot like genes. (Richard Dawkins first posited this theory in his 1976 book “The Selfish Gene,” with a chapter called “Memetics” -- where the word “meme” comes from.)

Memes, like genes, succeed if they are useful and if they can be replicated. Harambe was easily replicated. The Cincinnati Zoo released Harambe’s official photo, which ran with every news story. And footage from the incident was posted across virtually every news site.

That’s all it takes. Anyone with rudimentary Photoshop or Paint skills can “replicate” Harambe in a way other people can recognize.

And as his image was replicated across the Internet, it took on new meaning. “At some point the story has become less about the child’s life being in danger, less about the parents,” Johnson said, “and more a shorthand way of expressing that you’re sad about something, or mocking the way the Internet gets upset about something.”

The meaning of that shorthand changed depending on the context.

Early on, Harambe became a symbol for the disparities of mourning on the Internet. Critics asked why Americans seemed to care more about the death of a gorilla than about police killings of black people, while others joked that if Harambe had been a white gorilla, he’d still be alive.

Harambe’s image was soon being used in posts with racist overtones. Disparagingly comparing black people to gorillas and monkeys is a racist practice that dates back to the 1600s; Harambe provided a new spin on the old trope. In early June, memes comparing retired Australian rules football player Adam Goodes, who is indigenous, to the gorilla surfaced on Facebook. The athlete had once been called an “ape” by a 13-year-old girl.

Within a week of Harambe’s death, a white teacher in Louisiana posted a side-by-side photo of Harambe and Michelle Obama indicating someone had “shot the wrong gorilla.”

Some argued that Harambe’s name provided fodder for racist memes. “Harambe became a big meme thing because it’s a ‘funny African name’ that people can make fun of without feeling racist,” tweeted actor Kumail Nanjiani in August.

“For people who either are uncomfortable saying, ‘clearly, I am a racist,’ or for people who are uncomfortable publicly using the N-word or some other disparaging term, this is a way to convey that same message without doing so,” Johnson said.

Instead of typing out why you’re upset about something, if you use a Harambe meme, it conveys the same message in a way that’s recognizable and easy.

— Shontavia Johnson

Memes also linked Harambe to the deaths of beloved celebrities — of which there were many in 2016. Almost immediately after his death, Harambe was being Photoshopped at the pearly gates alongside David Bowie and Prince. As the year draws to a close, Harambe is routinely mentioned alongside people who died this year.

“There was a big tongue-in-cheek subtext to it, which is kind of a signature mark of the space that we call Weird Twitter,” said Brad Kim, the editor-in-chief of Know Your Meme. The denizens of Weird Twitter make absurdist jokes and memes, and sometimes those jokes catch on to the larger Internet.

And that has continued to replicate: Every time there’s another major celebrity death, Harambe shows up again. The Harambe meme mocks the way the Internet responds to death: a celebrity dies, and suddenly everyone on your newsfeed claims they were that person’s biggest fan.

Two other events fueled the rise of Harambe’s popularity. The video game Overwatch, released the same week that Harambe died, featured both a big gorilla character and a sniper character. The memes practically made themselves. That same week, the Unicode Consortium announced the new emojis that would be released in Unicode version 9.0. The list included a gorilla.

Both Overwatch and the new emojis had been in development for a long time before the Harambe incident. But for users, the gorilla’s appearance was like an inside joke, providing a convenient shorthand and a quick laugh.

The Unicode Consortium allows people to pay to “adopt” emojis. In August, the group announced that “RIP Harambe” had formally adopted the gorilla emoji.

By August, the Cincinnati Zoo had had enough. Its official Twitter account was deactivated, and the zoo issued a statement asking people to please stop sending Harambe memes. In October, the zoo quietly began tweeting again. Tweets from the account never mention Harambe, but every one gets replies that reference him.

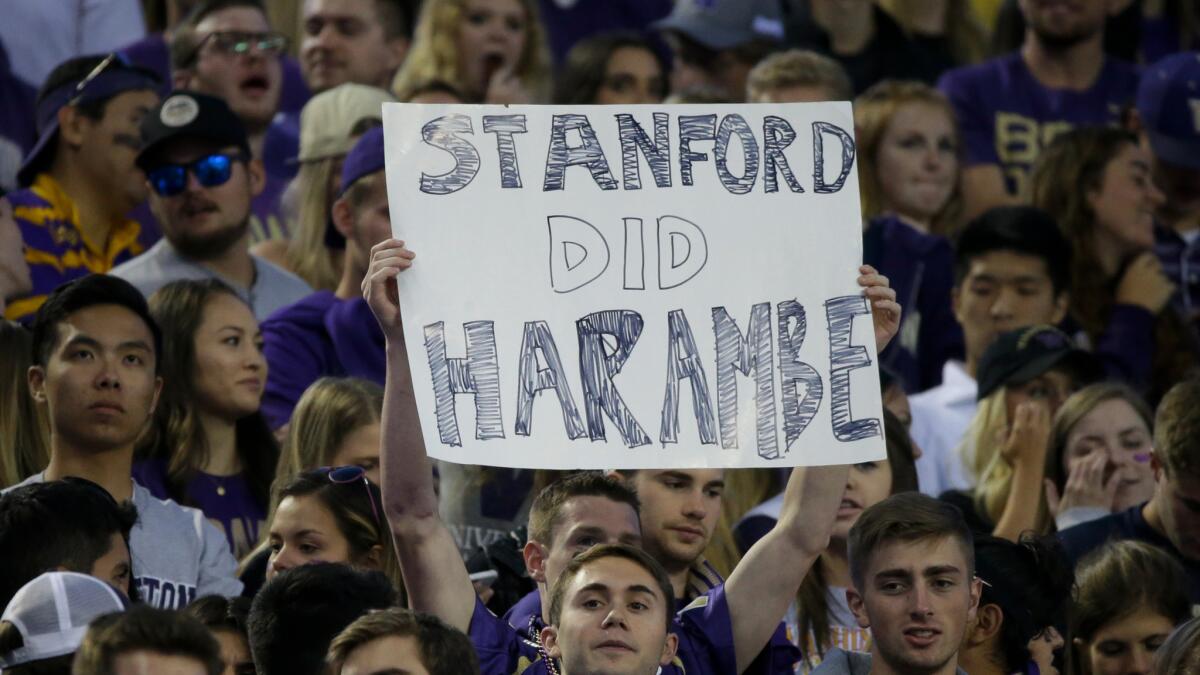

Harambe has become so popular that his name and face get spliced in with other memes, old and new. Someone holding a sign saying “Bush did Harambe” — a play on conspiracy theorists who accuse Bush of being behind 9/11 – appeared on camera behind an MSNBC anchor.

Lending this election season new levels of absurdity, Harambe at one point polled equally with Jill Stein in Texas and appeared on the campaign trail with Trump.

An untrue rumor swirled after the election that Harambe received 15,000 votes for president, and he was a punchline in Dave Chappelle’s opening monologue on “SNL” the Saturday following the election.

The meme has become a signifier of memes. Harambe is an easy laugh line, a sign that someone gets the absurdity of the Internet and wants everyone else to laugh at it too.

According to Google Trends, searches for Harambe spiked twice: When the news first happened, and in late August, when the zoo shut down its Twitter account over memes. Since then, it’s trended downward, though Harambe still pops up from time to time.

Harambe will eventually join the pantheon of outdated Internet memes. (When was the last time you saw a fresh joke about Keyboard Cat or Doge?)

But in 2016, he was the meme the Internet couldn’t escape.

Tweet me your favorite Harambe tribute @jessica_roy

ALSO

Here are some good things that happened during the terrible, no good, very bad year of 2016

7 L.A.-specific resolutions to make in 2017

How will California’s 2017 laws affect you?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.