Navajo military veterans struggle with housing

- Share via

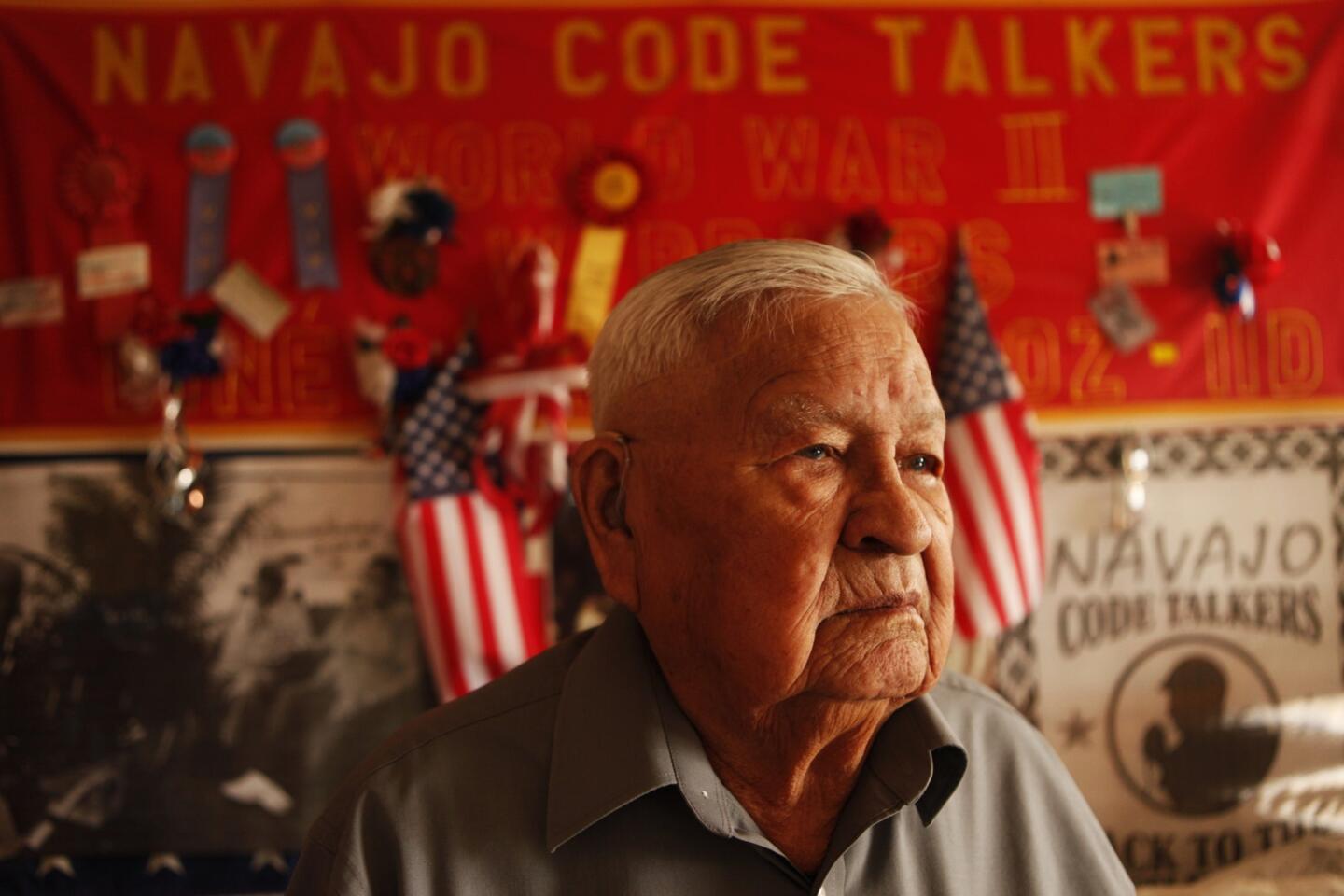

FARMINGTON, N.M. — In World War II he served as a Navajo code talker, one of the Marines who became legendary by using their native tongue to transmit messages the enemy could not decipher. Years later, to express its appreciation, the Navajo Nation built Tom Jones Jr. a house.

These days the 89-year-old Jones struggles to keep warm during winter because the only heat inside his house emanates from an antique wood stove in the living room. The electricity doesn’t work in his bathroom and the floor has worn away, exposing plywood beneath his feet.

Jones is one of many Navajo veterans, code talkers as well as those who served in Afghanistan or Iraq, who live in homes that are often as ruined as those they saw in battle. Some have no electricity or running water. The hallway in Jones’ small home is too narrow for his wheelchair.

“My desire is a house where I can be able to get around, to have a heating system so I can sleep well and enjoy life,” Jones said in the Native language of Diné, with which he spoke for the Allies through the war. “This is how I would want it.”

The living conditions of Navajo veterans highlight not just the never-ending battle against poverty on the 27,000-square-mile reservation, but the failings of a tribal effort to provide housing for those who served in the military.

Nearly 9,000 military veterans live on the reservation that straddles the New Mexico-Arizona border, more than half of them in what the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs says is substandard housing. For years, few funds were allocated for reservation housing for veterans, and much of what was allocated did not reach its intended targets because of mismanagement, U.S. and tribal officials say. Federal veterans’ home loan guarantees cannot be used to build homes on tribal land.

“There is a huge crisis taking place in our nation at the present time,” said Rick Abasta, spokesman for Navajo Nation President Ben Shelly. “If you travel through the reservation, you’ll even see some families living in storage sheds due to the housing situation.”

The tribe began constructing homes for veterans in the 1980s, and a $6-million trust fund for Navajo veterans created by the tribe allowed the launch of a home-building program in 1998.

The aim was to provide houses — free of charge — to veterans in need or help them pay for home repairs. Outside the Navajo Nation, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs provides myriad services for veterans, but a free house is unheard of.

“These veterans, they deserve housing — decent and sanitary housing — for the services that they provided this country. And that would probably go even more so with our Navajo code talkers,” Abasta said.

It’s unclear how many homes the Navajo Department of Veterans Affairs has built for veterans, in part because record-keeping problems have left tribal administrators without good data. David Nez, who heads the agency, says he believed it was in the hundreds, but in recent years the effort has been troubled with inefficiencies and money troubles, resulting in few new homes and incomplete maintenance of existing houses such as Jones’. Not one home was built last year.

In February, however, Navajo leaders signed a contract with Home Depot in Farmington to purchase building materials for veterans’ housing throughout the reservation.

It’s part of a $1.9-million project, paid for by the Veterans Trust Fund, which Shelly approved in the fall. But that’s just enough for 75 homes. There is a long list — in the hundreds — of veterans who are waiting for housing, according to Navajo Department of Veterans Affairs officials.

There is only so much the tribe can do, Abasta says, because of limited funding. “We meet with congressmen about these issues, but most often it falls on deaf ears,” he said.

Navajo veterans and their supporters say the program is run poorly.

Etta Arviso, who is lobbying to obtain better housing for several code talkers, says veterans tell her they face too much red tape in the application process. Others are discouraged by the wait.

“Now you can see how our Navajo code talkers are treated,” Arviso said. At Jones’ house she has erected a sign out front: “Navajo code talker needs a new home.”

Above the door are black scorch marks left by a lightning strike two years ago. Navajo tradition holds that one should not live in a dwelling where lightning has struck. It could lead to bad luck, sickness or worse. Jones’ wife, Alice Mae, died about a year after the lightning hit.

But Jones couldn’t move. He couldn’t afford it. He still can’t.

He is forced to spend most of his time in the living room, since he can’t get his wheelchair through the narrow hallway leading to his bedroom or bathroom. His caretaker or a family member has to carry him into other parts of the home.

When he was recruited into the military 73 years ago, Jones said, he was told that he would have whatever he needed after the war. He served as a corporal in the 3rd Marine division from 1943 to 1945 — a good portion of the time on the front lines, including at Iwo Jima.

When he returned home, he said, he was able to provide for himself, at one point working in the uranium mines. When he was younger he never asked for handouts, he said proudly.

“I was strong,” he said. “I would haul wood. I didn’t have problems money-wise.”

He laments his situation now. When his health took a downturn in 2007, he could no longer provide for himself. Jones has end-stage renal disease and undergoes dialysis twice a week. He has a hard time hearing and can barely talk. His U.S. Marines cap emblazoned with the Stars and Stripes seems to overwhelm his small frame.

Jarvis Jones, 37, who followed his grandfather into the Marines, says he’s disappointed and disgusted with how his grandfather and other code talkers live.

“It’s a lot of runaround,” the younger Jones said. “The story on the reservation is, ‘We have no funds.’”

About two hours south in the town of Smith Lake, Paul Endito, another Navajo veteran, says he’s struggling to get by and is forced to live in a cramped home that belongs to his mother-in-law. The house is so poorly insulated that he lines the windows and doors with blankets to keep out wind and dust.

He served in the Army during the first Gulf War, blowing up bridges and scraping out desert soil in 100-degree weather to create airstrips for military supplies.

After he returned to the reservation in 1994, he put in an application for housing because his wages as a cook at a senior center were too low to allow him to get a house of his own. It’s been 20 years.

“To this day,” Endito said, “they never got to me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.