Exonerated Wyoming prisoner pins hopes on compensation legislation

- Share via

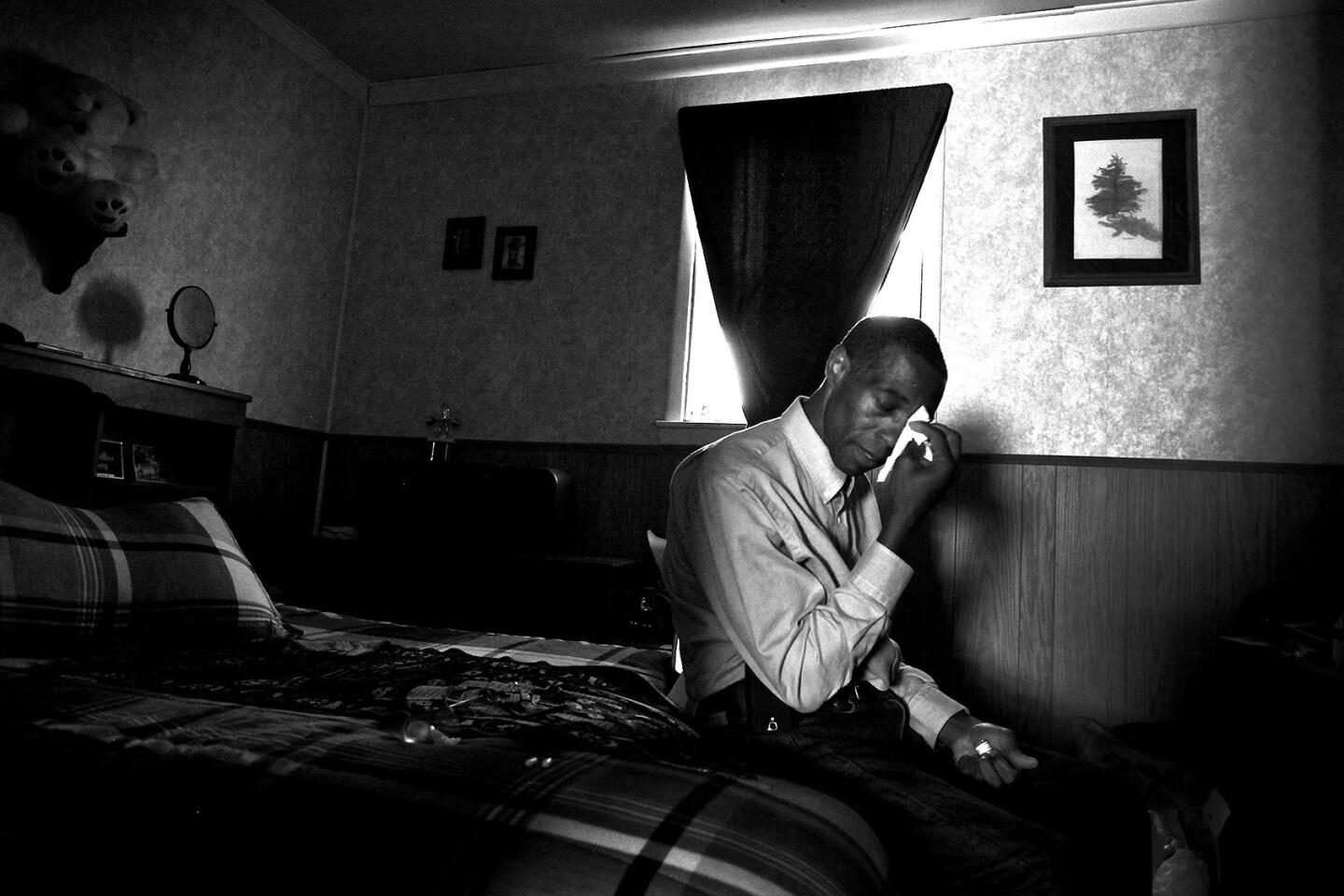

Reporting from CHEYENNE, Wyo. — When DNA evidence exonerated Andrew “A.J.” Johnson of rape after 24 years in prison, he got his picture in the paper and his freedom.

What he did not get was help starting over from the state that had imprisoned him.

He emerged from behind bars in 2013 at the age of 64, unemployed and in debt: $4,611.55 in child support had accrued while he was in prison.

“If I die today,” Johnson said recently, “I can’t afford to be buried.”

The number of prisoners exonerated of crimes has grown substantially with the advent of DNA testing and better forensics. But 20 states, including Wyoming, do not pay compensation for the years lost behind bars.

The falsely imprisoned in these cases are forced to file expensive lawsuits or seek special legislation from lawmakers who may be reluctant to pay, especially in cases where someone who spent years in prison for a crime they didn’t commit may have been guilty of others in the past.

Johnson had done time on a variety of theft and drug charges before his wrongful rape conviction in 1989. The Wyoming Legislature was left with a vexing question: How much are 24 years of a life like Andrew Johnson’s worth?

Their verdict was blunt: Nothing.

“People with prior records are more at risk for a wrongful conviction because they’re already in the system, and often that’s the first place police will look for a suspect,” said Saundra Westervelt, a compensation expert at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

In those cases, fighting for compensation can be a formidable challenge. Many exonerees are poorly trained men working low-level jobs, shadowed by the stigma of being ex-convicts, forced to file their own legal paperwork because they can’t afford attorneys, or can’t find one who will take their long-shot case. Nearly 60% of the 1,500 cases now listed in the National Registry of Exonerations are people of color.

But even in states that do pay compensation, a prior criminal record or indications that someone contributed to his conviction, for example, by associating with a gang, can prove an impediment. Florida has a “clean hands” provision disqualifying those with prior felony convictions, and requires prosecutors involved in the case to sign off on payments.

Former Laramie County Dist. Atty. Scott Homar, who handled Johnson’s case on appeal, continued to insist he was guilty, even after DNA cleared him, and noted that Johnson’s criminal record had contributed to his life sentence.

In many states, prior crimes are not an impediment to compensation. Colorado recently paid $1.2 million to an exoneree with a criminal record — including armed robbery — under its new compensation law. If Johnson had been convicted there, just eight miles south of here, he would be entitled to about $1.7 million.

Johnson acknowledged his past but said the state owed him just as it would anyone else unjustly imprisoned.

“Once you paid society back,” he said, “under the law, you are supposed to be another citizen of this country.”

**

Cheyenne is still the frontier town of Johnson’s youth, its downtown dominated by the red and gray sandstone clock tower of the Union Pacific Depot. But the Mayflower tavern where he once washed dishes has become a sushi bar. There’s now a yoga studio and something he’d never seen: a Starbucks.

In Wyoming, those about to be paroled from prison are prepared for freedom 18 months in advance of their release — trained to assemble vital records and to use cellphones and other unfamiliar technology. Exonerees get no such help.

Johnson had planned to move in with his mother when he got out of prison, but she died a few days before he was freed. Johnson joined his younger sister, who is disabled by multiple sclerosis and living in state-subsidized housing. The siblings split $250 a month in food stamps.

Donors moved by Johnson’s plight gave him a white 1997 Camry. But one morning he discovered his tires slashed and words scrawled on the windshield in black marker: “Walk rapist.”

New tires cost Johnson $272.34, draining his savings.

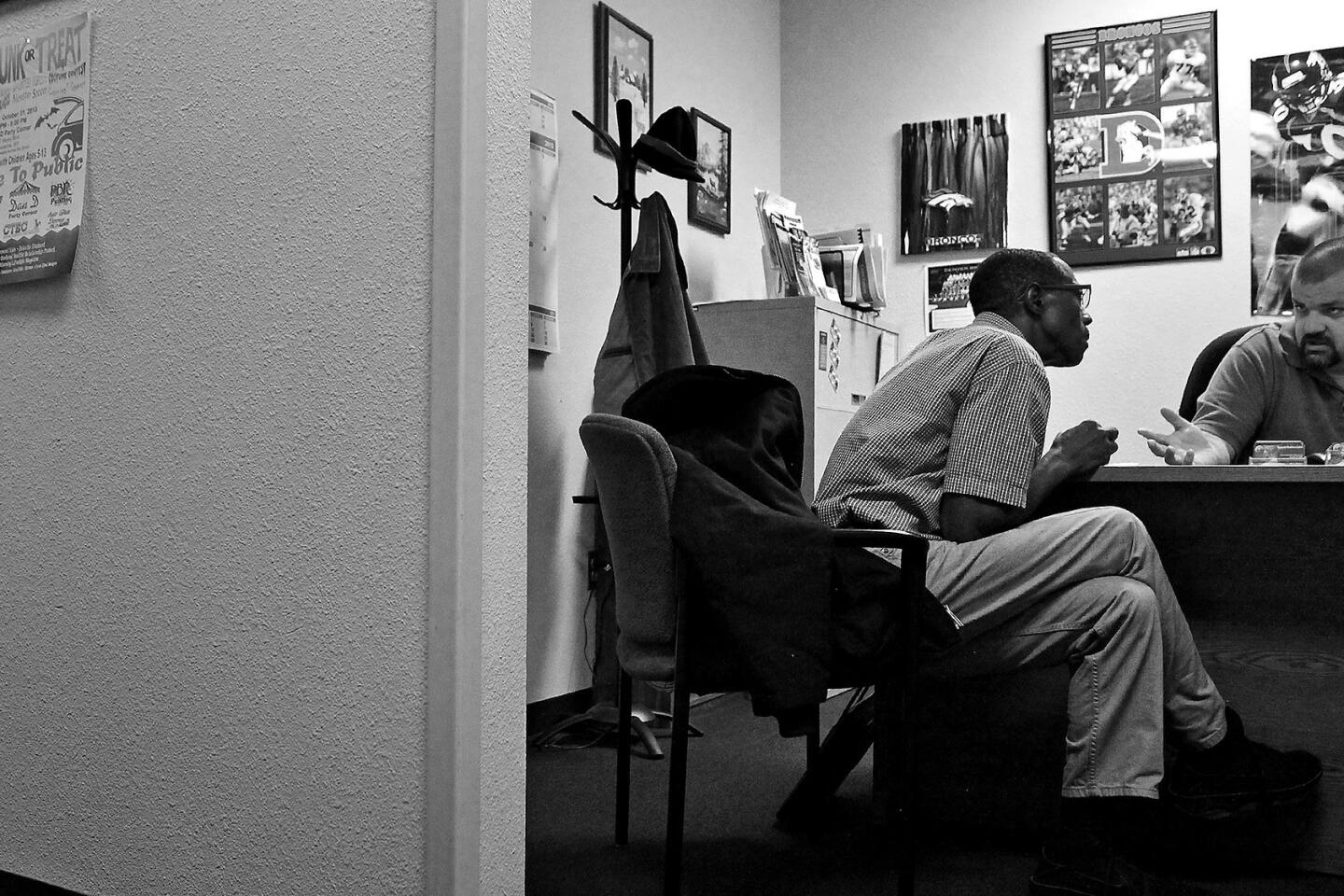

So that fall, Johnson trudged to the local unemployment office, broke and desperate.

“You just put your work history in right here,” an employee explained, pointing to a computer screen.

Johnson shifted his wiry frame forward, his narrow face eager. He had $1.36 in change rattling in the pocket of his donated winter coat and yearned to make enough to buy a pair of Red Wing work boots. “I just got out after 24 years,” he told the employee. “I got exonerated, and I don’t get any money.”

He followed the employee’s advice about online resumes and cobbled together a work history — dishwasher, fry cook, roofer. He figured his years filing legal appeals from prison were worth something, so he added law clerk.

The staffer searched online job postings.

“Doesn’t look like it’s bringing up much that you would qualify for,” he said.

Johnson’s attorneys, after launching Johnson’s successful appeal, now were proposing a state law that would compensate exonerees up to $500,000.

Johnson had wanted to sue police and prosecutors, but his lawyers advised that the proposed law was a better bet, even though they would have to lobby a Legislature dominated by tough-on-crime Republicans.

“What is the price of freedom?” his attorney told him. “We’ll find out.”

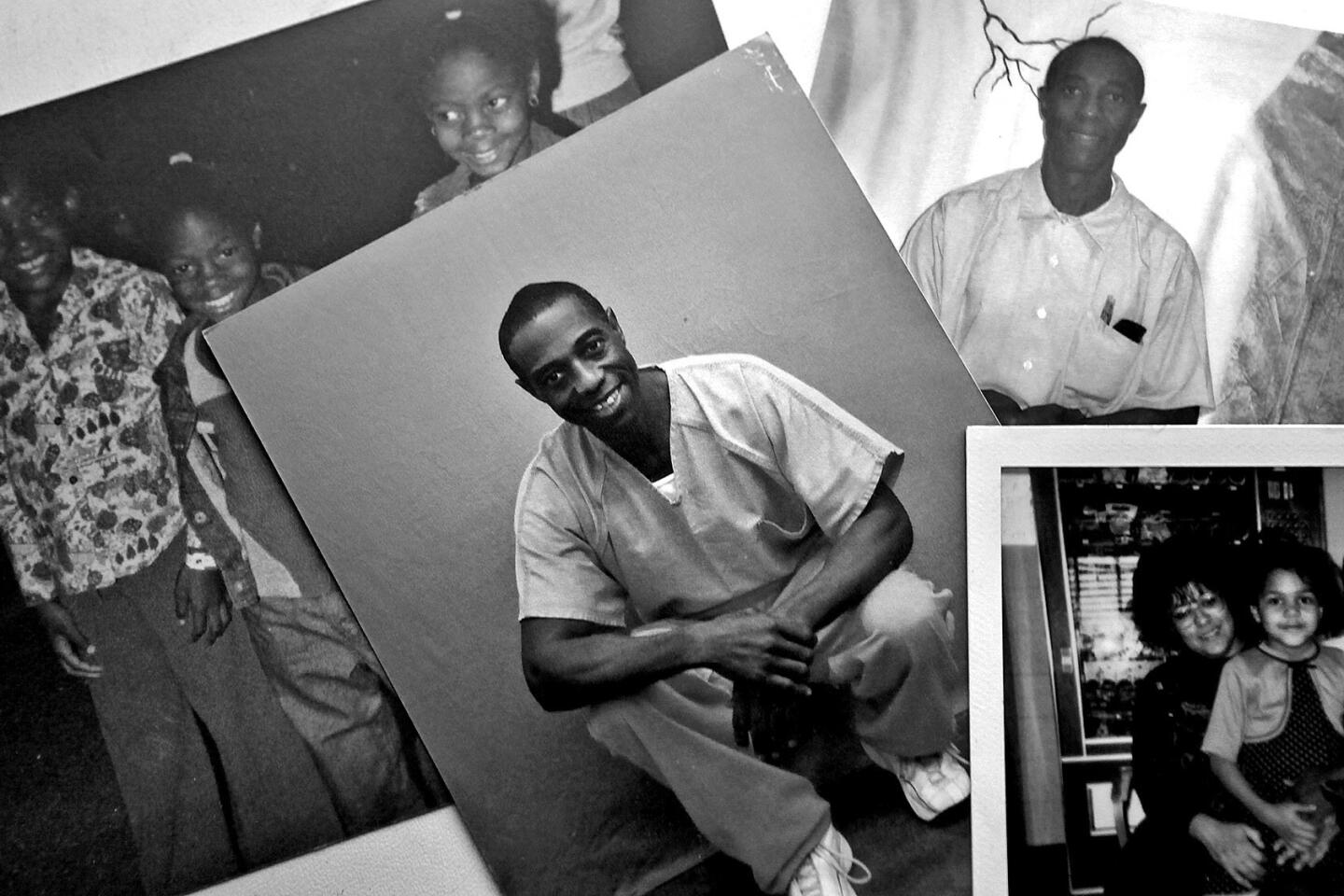

Johnson knew how precious freedom was even before his wrongful conviction. Tempted by easy money and drugs, he had served more than a decade of hard time, mostly for robbery.

But that did not make him a rapist.

He had grown up poor, a young black man in a state that is about 90% white.

His father died when he was 16, and Johnson had to work after school to help support his family. He had always been chatty, nimble, forever tinkering with machines. Inspired by the operatives on the television show “Mission Impossible,” he developed a sideline: safe-cracking.

In 1968, the year he graduated from high school, Johnson was nabbed robbing a grocery store safe. He served more than a year in prison.

After his release he married, settled in Cheyenne, had two daughters and took up roofing. But three more convictions and a divorce followed. By 1987, he was out of prison once more; he found a girlfriend and moved in to help raise her 4-year-old daughter.

He was up for a $2 raise at a new job when he was arrested again on June 10, 1989, and charged with raping a white woman, a friend’s fiancee.

On Sept. 27, 1989, an all-white jury deliberated for less than a day before convicting Johnson of aggravated burglary and first-degree sexual assault.

Johnson married his girlfriend while in prison, but they saw little of each other, as he was repeatedly transferred out of state due to overcrowding. By 2006, they had divorced.

Two years later, lawyers at the nonprofit Rocky Mountain Innocence Center responded to Johnson’s pleas and successfully lobbied state lawmakers to pass a DNA-testing law. Then they persuaded a judge to order retesting of the rape kit from his case.

When new DNA tests excluded Johnson and matched the victim’s fiance, Dist. Atty. Homar requested additional tests. They proved inconclusive.

A judge ordered a retrial. In April 2013, Johnson was released on $10,000 bond.

Homar dismissed the new DNA tests, saying Johnson might have used a condom or failed to ejaculate.

Ultimately, Homar said too many years had passed to pursue a new trial, while also conceding that the accuser had “credibility issues.” In July 2013, he asked a judge to dismiss all charges against Johnson due to insufficient evidence.

“This is not an exoneration,” he said at the time. But months later, a judge made a finding that Johnson was in fact innocent.

Johnson’s bond money was refunded. He used it to bury his mother.

With little chance of a good job, Johnson’s best hope was the proposed compensation law.

The bill introduced in March called for paying exonerees $100 per day in prison, up to $500,000, disbursed in annual increments of $50,000.

But the legislation drew fire almost immediately. Opponents warned that the law could reward criminals freed on technicalities.

A Republican lawmaker declared that compensating Johnson would be a mistake.

“If you ask the prosecutor,” Rep. Bob Nicholas said, “he will tell you with hand over his heart this man is not innocent.”

The bill was tabled, and later that month, the Legislature adjourned without passing it.

Twitter: @mollyhf

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.