‘Dear murderer’: With a letter a day, West Virginian tried to remind coal executive of his role in 29 deaths

Reporting from Ithaca, New York — He was the highest-paid and best-known person in the U.S. coal industry, but his career ended in disgrace.

In May 2016, Don Blankenship, the former chief executive of Massey Energy Co., began a one-year sentence in federal prison for his role in an explosion six years earlier in West Virginia that killed 29 coal miners.

To Ann Bybee-Finley, a 27-year-old West Virginia native and graduate student in agriculture at Cornell University, the sentence seemed trivial compared with the suffering that had occurred on his watch. She was motivated by sympathy for the victims and their families and her own brush with death, having recently suffered a heart attack.

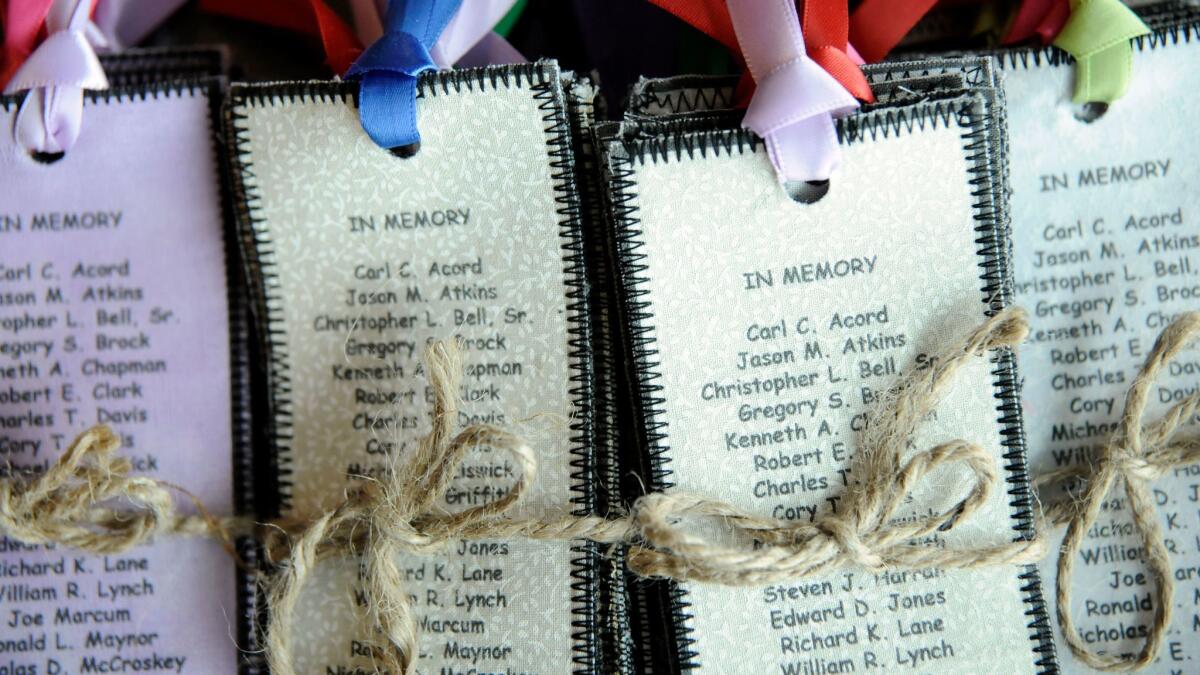

So she invited survivors and anybody else to write the chief executive letters with the aim of sending him one each day he spent in prison.

“With one letter a day, perhaps Don Blankenship’s year behind bars will be a year of reflection, filled with daily reminders of pain and grief,” she wrote in a post on Facebook announcing the campaign, which she called “Making One Year Count.”

She also recruited letter writers from the Cornell area in upstate New York.

Emails and Facebook posts poured in. They were filled with sorrow and anger.

“I was just another face in the crowd that cold April night,” wrote Emily Pritt, who lost her boyfriend and two of his relatives in the explosion. “I’m just another heart broken. I’m just another person who received that dreadful phone call that makes every coal miner’s family member afraid to answer the phone during his shift.”

She and her longtime boyfriend, Cory Davis, were both 20 when he died.

“He was a redneck, camo-wearing, hunting, fishing, coal miner’s son from the hollers of Cabin Creek,” she explained to Blankenship. “I was a preppy, avid athlete, outgoing, never ate deer meat in my life, banker’s daughter from Campbell’s Creek. He was from East Bank, I was from DuPont. We came from different worlds, but when we crossed paths — our worlds became intertwined forever.”

Gary W. Price Jr. of West Virginia wrote as a friend of Davis’ parents.

“Dear murderer,” his letter to Blankenship began. “Please allow me a few [minutes] of your year to tell you how your greed, selfishness and complete lack of remorse has affected my friends Tommy and Cindy Davis.”

I hope you use this year to think of all the damage you have done, all the lives that you have shattered, and all the people you have changed.

— Gary W. Price Jr.

“You could’ve changed everything, but chose money and profit over those men’s lives,” he wrote. “I hope you use this year to think of all the damage you have done, all the lives that you have shattered, and all the people you have changed. I feel no sorrow for you.”

Bybee-Finley printed out the emails and Facebook posts and each day sent one to Blankenship at the minimum-security Taft Correctional Institution in Kern County, Calif. The postman thanked her once for sending so much mail.

A month in, she learned that the prison required a return address. She had not been including one, so she re-sent those letters.

Blankenship, 67, grew up poor in West Virginia coal country and was raised by his mother, who ran a gas station and convenience store. He joined a Massey subsidiary as an accountant in 1982, rose through the ranks while developing a reputation as a union buster, and became chief executive in 2000. He was paid $17.8 million the year before the disaster and received deferred compensation of $27.2 million upon retiring months afterward.

Bybee-Finley had no way of knowing whether he was reading the letters. But then one day she received a reply.

“The families of the [Upper Big Branch] miners are no doubt hurt, angry and wanting me to suffer for their loss,” he wrote by hand last June. “It’s not my intent in this note to change that and unfortunately I could not change it if it were my intent.”

He spent most of the next six pages maintaining his innocence, as he had done in court and in a booklet he later produced portraying himself as a victim of a government conspiracy and a “political prisoner.” He said the explosion — which sent flames shooting through 200 miles of underground tunnels — was an accident caused by a freak buildup of natural gas in the mine.

“Why am I writing you all of this?” he wrote to Bybee-Finley. “Because as best I know what I have written here is true and Cory … and all the miners deserve that someone tell the truth of what happened to them.”

His version of events contradicted multiple investigations that concluded that the company’s failure to control the buildup of highly flammable coal dust in the mine played a major role in the disaster. Blankenship had beaten two felony charges, but he was convicted on a misdemeanor of conspiring to violate federal safety standards. One year was the maximum sentence.

In response to another writer, Blankenship defended himself from accusations of being out of touch with workers.

“I spent my young life with coal miners,” he wrote. “Put gas in their cars, played in their baseball league, went to their churches, grieved with their families. I spent my adult life improving mine safety and paying miners the best wage the company could afford at the time.”

Bybee-Finley found his letters respectful, even if she disagreed with him. She had never expected him to change his beliefs.

Bybee-Finley noticed that male writers tended to focus on the chief executive’s misdeeds, while most of the women wrote about the survivors and victims.

The emails and Facebook posts kept coming. Bybee-Finley noticed that male writers tended to focus on the chief executive’s misdeeds, while most of the women wrote about the survivors and victims.

In “my personal opinion, he only got a little slap on the wrist while all we have is pictures of our loved ones and tombstones,” wrote Robbie Mann, whose uncle, Kenny Chapman, died in the mine. Mann said Blankenship deserved “life in prison without the possibility of parole.”

It’s “what I would have gave him if I would have been a judge in that trial,” he wrote.

A high school teacher in West Virginia heard about the project and turned it into an assignment for her students. Other correspondence came from strangers from outside West Virginia who felt the same sense of outrage that Bybee-Finley did and were grateful for a chance to express it.

Soon there were 150 messages.

Some writers attacked the coal industry, which once dominated the West Virginia economy, but by 2015 employed just 15,000 miners, or 2% of the state’s workforce.

“For far too long, you and your cronies have bought and paid for this state, via ensuring the most corrupt politicians possible get elected,” wrote Jami Hadden, an IT project manager from a West Virginia mining family. “By investing millions of dollars in local contests, any opponent has no chance of competing. So in return for positions of power, these politicians look the other way while you rape the land, disenfranchise the people, and literally work employees to death, so you can turn a little extra profit.”

“You have helped create conditions of such hopelessness that people turn to alcohol, pills and heroin,” she went on. “It is no mistake or surprise that [West Virginia] leads the nation in addiction rates and overdoses.”

By the summer, two months into the campaign, the steady stream of emails and posts had become a trickle.

Blankenship was out of the news, which was now dominated by severe floods in the state.

Bybee-Finley put out the word to various activist groups that she needed more letters. But hardly anybody responded. Even friends were too busy to help her with the cause.

“If it comes to it, I’ll write him a letter a day,” she vowed. But there was no way she could keep that up.

By the fall, Bybee-Finley rarely received new correspondence. The final total of emails and Facebook posts was about 180, or half her goal.

She was disappointed, but found solace in that she had provided a way for people to raise their voices against the coal industry that she said has “sucked the wealth out of West Virginia.”

Blankenship was transferred from the prison to a halfway house in early March and a month later to home confinement. His sentence ended Wednesday. He could not be reached for comment, but in a series of tweets that morning he attacked the official investigations and accused the government of hiding the truth and stifling his free speech.

“By law, he served his sentence,” Bybee-Finley said. “But I think our laws are unjust if they value the lives of workers so little.”

Slavin is a special correspondent.

ALSO:

Things to know about Trump, Comey and special prosecutors

Congress votes to allow controversial hunting practices in Alaska

A building boom and climate change create even hotter, drier Phoenix

UPDATES:

12:23 p.m.: This article was updated with information about Blankenship’s release.

This article was originally published a 3 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.