An American president is about to visit Cuba for the first time in 90 years

- Share via

reporting from WASHINGTON — Cuba has stood for decades in U.S. politics as a bitter symbol of the Cold War, but the recent diplomatic thaw is scrambling that narrative as Americans increasingly see the Caribbean island nation as a land of exotic tourism and lucrative business opportunities.

Even as those giddy expectations collide with the reality of Cuba’s slow changes, President Obama on Sunday is set to become the first sitting president to visit in 90 years, a reward of sorts for the communist-led government in Havana.

Obama is scheduled to arrive with First Lady Michelle Obama and their two daughters, Malia and Sasha, for a full-family, two-day embrace of the push to normalize relations, complete with cultural tours, a baseball game and even dinner at the Palace of the Revolution, the seat of President Raul Castro’s authoritarian government.

U.S. officials say Obama will not meet or appear near the president’s brother, Fidel Castro, who led the communist revolution in the 1950s and ruled until 2008. Now 89, he is rarely seen in public.

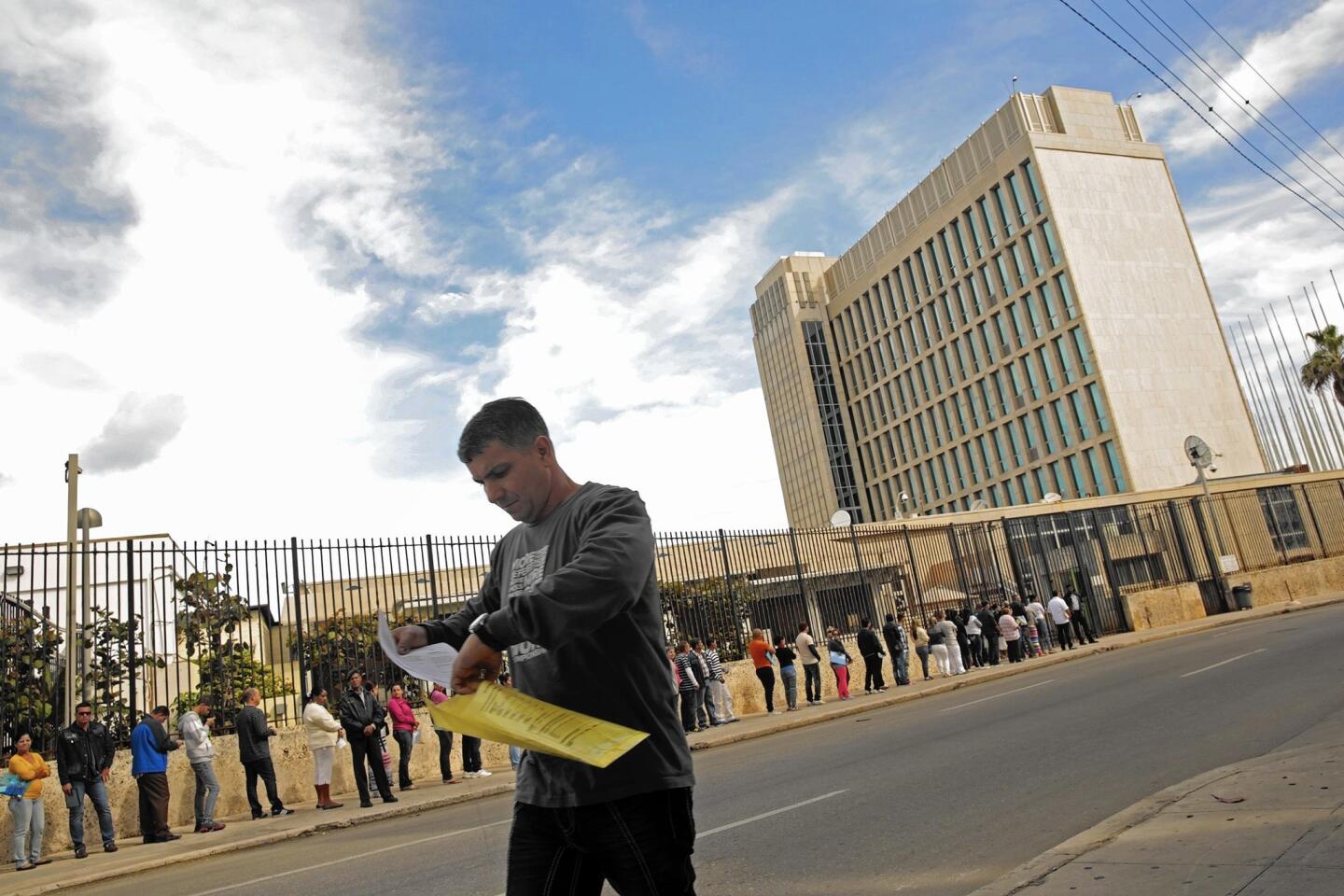

“It signals a new beginning between our two countries and peoples,” said Jeffrey DeLaurentis, charge d’affaires at the U.S. Embassy in Havana. He said he is “working hand in hand” with Cuban authorities to arrange Obama’s trip.

Congress, nonetheless, refuses to end its trade embargo and isn’t about to hand back the U.S. naval station at Guantanamo Bay, as Cuba demands. Obama is expected to sharply criticize his hosts for human rights abuses, and plans to meet with political dissidents the White House has chosen.

Although Obama will speak to a large Cuban audience in Havana, the White House had still not received the OK for the speech to be broadcast nationwide on Cuban TV.

“This is a speech to the Cuban people, and that includes Cuban Americans,” said Ben Rhodes, Obama’s deputy national security advisor. “And all those different constituencies are enormously important stakeholders for the policy that we’re trying to pursue, and the change that we’re trying to pursue.”

Some political walls already have tumbled. In the last week, hard-line U.S. political opposition to easing tensions appeared to melt even in Florida, the locus of anti-Castro anger over the decades.

Hillary Clinton, who won the state’s Democratic presidential primary, pointed to Cuba as an emblem of her foreign policy, showing her commitment to chipping away at dictatorships around the world.

Donald Trump, who won the Republican presidential primary, mostly complained that Obama “should have made a better deal” before he reversed U.S. policy on Cuba.

Those are easier positions to take now that polls show nearly three-quarters of Americans approve of the restoration of diplomatic ties and reopening of embassies last summer.

Corporate executives are eagerly eyeing the hotel, airline and telecommunications opportunities in Cuba, and several business leaders and entrepreneurs are traveling to Havana as part of the American delegation.

The shift in attitudes stems in part from the passage of time. The generation of early Cuban exiles in the U.S. is giving way to younger immigrants, who tend to come for economic opportunities and are not driven by ideology.

“The younger Cubans are voting more like Latino voters, on the economy, jobs and health care,” said Dan Restrepo, Obama’s former senior advisor on the Western Hemisphere.

Many of the recent immigrants welcomed Obama’s decision in 2009 to let them send more money back to their families in Cuba and to visit them more often.

The response persuaded Obama to authorize secret negotiations with Cuban officials in 2014, talks that took place in Canada and at the Vatican.

By the time Pope Francis visited Cuba last fall, the easing of tensions was celebrated by Latinos in the U.S., a sharp contrast with the protests that attended Pope John Paul II’s visit to Cuba in 1998.

Still, for all the historic change, Cuba has yet to take the steps that many Americans say are needed to normalize relations.

“President Obama never went into this with a quid pro quo approach,” said Peter Hakim, president emeritus of the Inter-American Dialogue think tank. “But it’s clear that the Cubans aren’t providing many quos.”

In a scathing editorial, Granma, the official Communist Party newspaper, warned against expecting Cuba to “abandon its revolutionary ideals” in the interest of improved ties.

For true normalization, Congress would have to lift the trade embargo and the U.S. would have to relinquish the territory it holds at Guantanamo Bay, said Josefina Vidal, the head of American affairs for the Cuban Foreign Ministry and a top negotiator in the normalization process.

She cautioned last week that Havana and Washington have different definitions of “human rights.”

Dozens of Cuban dissidents have been rounded up in recent months. Most were released after a brief detention, and the policy appears aimed mostly at thwarting organized protest, activists say.

In Congress, some lawmakers have criticized Obama’s trip, including three Cuban Americans: Sens. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Bob Menendez (D-N.J.).

Human rights advocates echo their concerns.

“It is crucial President Obama focuses on human rights and political reform in Cuba,” said Marion Smith, executive director of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, who is working to organize protests during Obama’s visit. “Otherwise his visit is an insult to the victims and dissidents whose lives have been made worse since the U.S. recognition” of Cuba.

Aides to Obama say that he will speak forcefully on the need to improve human rights and allow democratic reforms when he sits down with Raul Castro and that he will meet privately with dissidents and other community leaders of his choosing, not Castro’s.

In public, Obama will emphasize common ground with Cuba. He will attend an exhibition baseball game between the Tampa Bay Rays and the Cuban national team. Michelle Obama will hold her own public events, including a meeting with Cuban students who have studied in the United States.

Decades of ostracism of Cuba had the effect of isolating the United States in the Americas. The U.S. was the only country in the hemisphere that did not have relations with Cuba, and the issue was a sore point at regional summits year after year.

By ending the estrangement, diplomats say, Obama has improved U.S. standing throughout Latin America. Argentina, where Obama travels after Cuba, recently replaced its leftist president with a centrist, free-market proponent.

“The improvement of U.S.-Cuba relations has a salutary impact in Cuba, in the U.S. and in all Latin America,” said Jorge Dominguez, an expert on Cuba and professor of international affairs at Harvard University.

Obama’s trip to Cuba also coincides with the possible signing of a cease-fire agreement between Colombia and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, a guerrilla group that has been waging the hemisphere’s longest insurgency.

The two sides have been negotiating for months in Havana, and if an agreement is reached, Obama will be present to oversee the signing, another remarkable step in U.S. relations with Latin America.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.