Dogs, Deepak Chopra, Instagram weddings and other signs of change among Iran’s middle class

- Share via

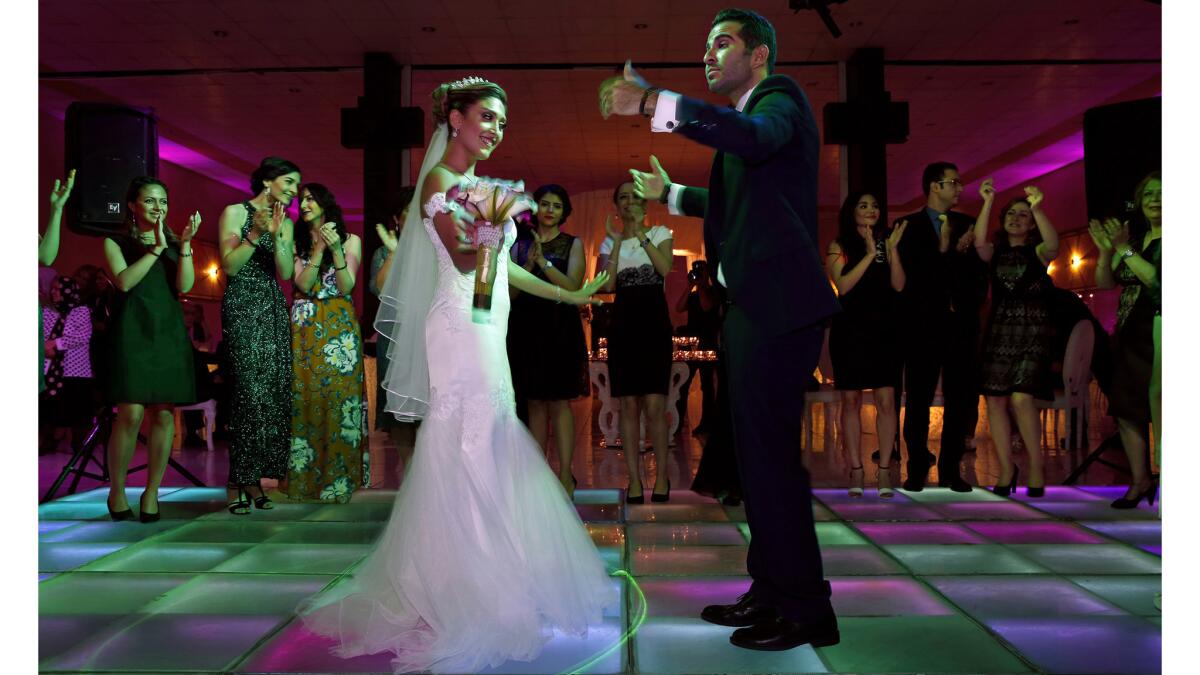

Tehran — The groom wore a navy blue tuxedo, the bride a custom-made gown with a fish-scale pattern inspired by pictures she found on Instagram.

Waiters passed around French tarts as guests crowded a dance floor pulsating under strobe lights. When the DJ played “Gangnam Style,” a cheer went up from the young women in tight dresses, salon-styled hair falling down their bare shoulders.

The wedding reception was like so many — except that it took place in Tehran, the capital of an Islamic republic whose ruling clerics take a dim view of such displays of skin and secular, Western-oriented tastes.

“We represent the change in society,” said the groom, 30-year-old Sarmad Kodeiri.

Iran’s theocracy — whose top clerics still lead “Death to America” chants at Friday prayers — has exercised strict control over public behavior since taking power in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. But beneath the surface in this country of 80 million people, the hard-liners quietly are being challenged by a large urban middle class that has grown weary of religious strictures and more attuned to global trends.

In Tehran, fashionable women wear the mandatory attire — head scarves and long coats — loosely around their hair and snugly around their bodies. Young men picnic in parks with their girlfriends despite admonitions against mingling of the sexes. Satellite dishes are officially banned, but more than half of Iranians use them at home to watch foreign broadcasts that conservatives call an affront to Islamic values.

To avoid social unrest, Iran’s mullahs tolerate a certain amount of cultural rebellion, adjusting their standards like a thermostat as they read the public mood. Lately, Iran’s people — more than 60% of them younger than 30 — have signaled that they want less interference in their private lives.

In 2013, voters elected as president a moderate cleric, Hassan Rouhani, who supports greater personal freedoms and better relations with the United States. He has said police have no business enforcing Islamic values, angering arch-conservatives but bolstering his standing with the urban middle class.

But Shiite Islam remains the law of the land — and crackdowns can come at any time.

Lately, Iran’s people — more than 60% of them younger than 30 — have signaled that they want less interference in their private lives.

This spring, Tehran authorities announced the deployment of 7,000 undercover “moral police,” boosting a force that patrols the streets for violations of Islamic dress and behavior. The cops have been known to scrub makeup off women’s faces and close barbershops deemed to be giving Western-style haircuts.

In July, police raided a party on Tehran’s outskirts and arrested 150 young men and women for “immoral activities.” Their offenses, the semiofficial Fars news agency reported, included attending a mixed-gender gathering and planning to record a video to be distributed to Persian satellite TV stations abroad.

Authorities this year have also rounded up people for posting photographs on social media in which they appear to be modeling for a camera, which is seen as indecent.

Mohsen Ariya, co-founder of the studio that photographed Kodeiri’s wedding, said plainclothes police stormed a client’s reception two years ago and seized his team’s cameras and film equipment, accusing them of abnormal behavior. He was acquitted in court but found his Instagram account temporarily blocked and his name on a paramilitary blacklist online — a method of intimidating offenders.

“They said the style of the wedding was provocative,” Ariya said. “To some people, anything can be provocative — even a woman’s fingernail.”

Yet signs of change are everywhere in Tehran — small displays of resistance that show a middle class, despite its economic and political frustrations, determinedly testing the limits of what the government will allow.

In Iran, simply owning a dog is a political act.

The country’s traditionalists generally frown upon man’s best friend, which they regard as unclean and a mark of Western decadence. In a park on the outskirts of Tehran, signs warn, “No Dogs Allowed.”

By day, security guards have been known to shoo away people who bring their pets here. But in the evenings, nobody bothers the furry congregation gathered on a wide grassy slope.

Under a towering lamp that cast a pale golden light, Maggie, a German shepherd, raced back and forth across the lawn. A large gray husky named Jessica — after Jessica Alba, said her young male owner — did tricks on command. Shibel, a Shih Tzu in an “FBI” T-shirt, chased lustily after the females.

Susan Mokhtiari, 39, said the park was one of the only places she could bring Rubeena, her 4-year-old terrier. Many of her neighbors shun her. When colleagues at a state-run insurance company saw a picture of the dog on her laptop, they called canine ownership a disgusting hobby.

“I believe a man or woman who has a pet is a kinder person,” Mokhtiari said. “It’s not like I’m saying I’m better than anyone, but I am asserting my right to be different.”

Setayesh and Sogham Ghadimi — 16-year-old twins dressed identically in shiny black high-tops, bangs poking out from under their head scarves — come every evening with their two dogs. One recent night, a police officer yelled at Setayesh, “Cover your hair!”

Another time, she was chided for the English words printed on her head scarf.

“This is our way of rebelling, to show that we are different,” she said. “People always find ways to show their real personalities, no matter what the government says.”

Some Iranians turn to books for a break from state-sanctioned religion.

Although proselytizing for other faiths is punishable by death, authorities have allowed publication of a small number of spiritual texts that veer outside Iran’s somber Shiite orthodoxy, which emphasizes mourning and sacrifice.

Inside a small, tidy bookshop in central Tehran, where postcards of Western philosophers are tacked to the walls, owner Mohammad Ali Behjat pulled out works by Sufi mystics, Zoroastrian philosophers and Indian American spiritual guru Deepak Chopra.

Behjat, whose family founded one of the country’s few independent publishing houses, said the books appealed to Iranians seeking some psychological space from the establishment.

“It doesn’t mean that people are atheist or anti-Islam,” Behjat said. “It means the middle class is fed up with the official version of religion that is imposed on them politically.”

The texts are legal and officially licensed, but the readership is small. Behjat sells fewer than 2,000 Chopra books a year.

One customer, Mohammad Rashidi, 32, a member of the country’s marginalized Kurdish minority, leafed through a coffee-table book about Kurdish archaeology.

“I’m looking for my identity,” said Rashidi, who holds an archaeology degree but works as a computer technician. “That’s why I studied archaeology and history, to learn about my ancestors and my roots, and to get some distance from the revolutionary perspective.”

Theater is also testing the limits of the revolutionary order.

One recent production was a local adaption of “Ivanov” — by the 19th century Russian playwright Anton Chekhov — with the central character re-imagined as a liberal intellectual depressed by Iran’s political and economic stagnation.

Outside the red-brick theater, men in skinny jeans chatted with women who wore scarves fastened far back on their heads. When the lights went down in the auditorium, one woman removed her head scarf altogether.

But there were limits. At the end of the second act, Chekhov’s text calls for Ivanov’s wife, Anna, to walk in on him kissing his girlfriend. In the Iranian production, Anna discovers recordings of Ivanov and the girl speaking to each other, betraying the affair. The characters never kiss.

In private and after dark, Iranians feel freer. At Kodeiri’s wedding reception, in a secluded garden outside the city, men and women mingled comfortably.

The bride and her friends eschewed head scarves. Men wore neckties, which are hardly ever seen in public because traditionalists view them as a symbol of the West.

Kodeiri, who works in telecommunications and is the son of retired bureaucrats, said the couple tried to blend modernity and tradition. A cleric presided over the official marriage ceremony, though it was held not at home, which is customary, but in a park before a team of cameramen who would edit it into a video.

The bride, Shehrzad Bolandkish, a 30-year-old information technology worker, scoured social networks for decor and dress ideas. The wedding budget was relatively modest: $12,000, most of which Kodeiri financed from his savings.

“We tried to do it our own way,” he said. “We convinced our families. We were influenced by the Internet, but I think our style represents the style of about 20% of the people of Iran.”

Before they left on their honeymoon to Eastern Europe, Kodeiri reflected on his favorite part of the wedding. It came at the end of the night, he said, when he and his bride danced a tango.

Mostaghim is a special correspondent.

Twitter: @SBengali

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.