A narcissist or an eccentric? The man behind the Ghost Ship warehouse left conflicting impressions

If the fire is determined to be an arson, prosecutors could bring murder or aggravated arson charges — with one count for each person killed.

- Share via

From the moment tenants met Derick Ion Almena, they knew he wouldn’t be an ordinary landlord.

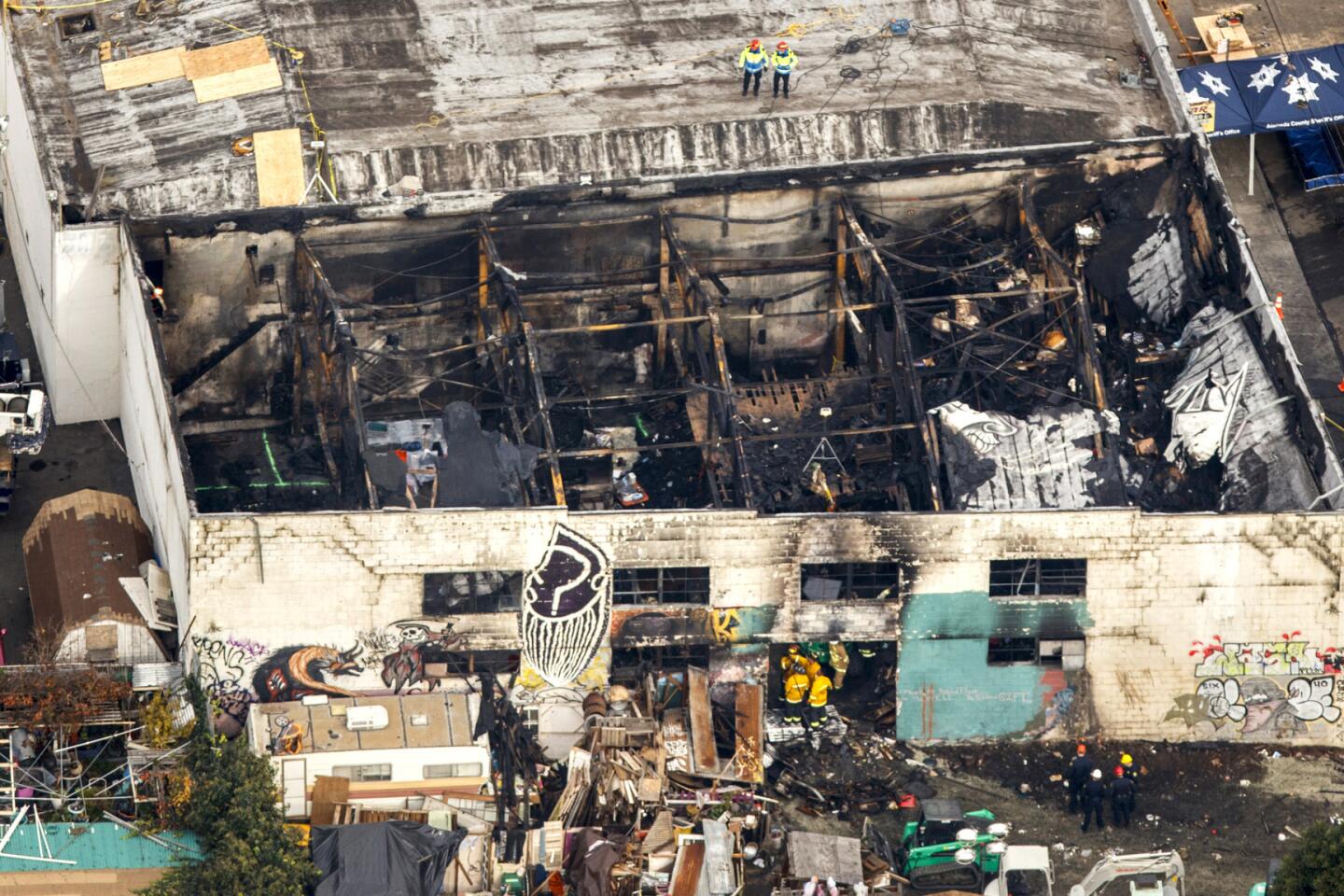

The 10,000-square-foot warehouse he oversaw in Oakland’s Fruitvale neighborhood was overflowing with elaborate decorations, broken musical instruments, beat-up furniture and woven rugs. It struck some visitors as an exotic maze, and others as a terrifying fire hazard, as ungovernable as the personality of the man who operated it.

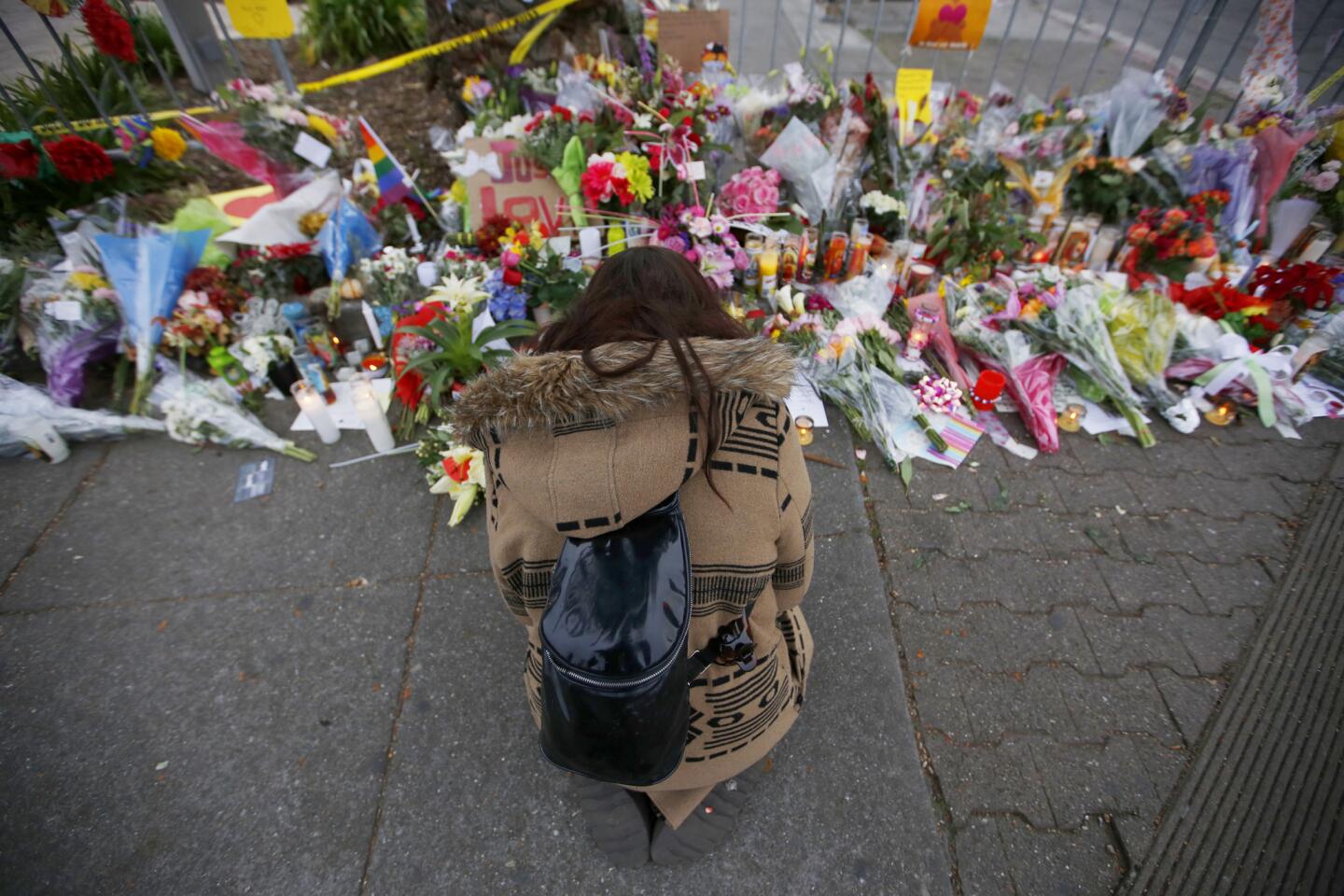

As firefighters continued Tuesday to sift through the remains of the worst structure fire in the U.S. in more than a decade, more details have emerged about Almena, who ran the warehouse, known as the Ghost Ship, as a physical extension of himself.

Wherever he went, Almena, 47, made a strong impression. Many of those who knew him described him as a narcissist and an opportunist. They said he deftly manipulated those around him, including his longtime partner Micah Allison, 40, who lived with him and their three children on the warehouse’s second floor.

“He is able to charm people, but when they don’t go along with what he wants he will threaten people,” said Allison’s father, Michael Allison.

Others judged him more gently as a misunderstood eccentric, a “crazy uncle,” who leased the warehouse and sublet it to musicians and artists who couldn’t afford, or didn’t want, a more conventional living space.

“He has kind of childlike characteristics,” said Libby Physh, 25, who lived in the warehouse for about five months in 2014, paying $500 a month for one of the half-dozen trailers parked on the Ghost Ship’s ground floor.

Physh said that Almena was devoted to his dream of turning the warehouse into a performance space, and she often saw him repairing parts of the building himself, something Almena has acknowledged he did without the proper permits.

“I really don’t think from what I know of Derick that he had malicious intent at all in creating in this space,” Physh said. “I don’t believe it.”

Neither Almena nor Allison could be reached for comment for this story. But in a disjointed interview on NBC’s “Today” show Tuesday morning, Almena repeatedly expressed sorrow for the 36 lives lost in the fire.

“I’m only here to say one thing: I’m incredibly sorry and that everything that I did was to make this a stronger and more beautiful community and to bring people together,” he said. “People didn’t walk through those doors because it was a horrible place. People didn’t seek us out to perform and express themselves because it was a horrible place.”

When asked if he was accountable, he said, “No, I’m not going to answer these questions on this level. I’d rather get on the floor and be trampled by the parents. I’d rather let them tear at my flesh...”

Almena’s legal battles with some of the tenants and partygoers who visited the Ghost Ship are well-documented, but little is known about his life before he popped up in Oakland’s underground art scene.

Michael Allison said his daughter and Almena both grew up in Southern California and have lived together as wanderers, organizing their lives around Burning Man and other festivals. They had an apartment for a time near MacArthur Park in Los Angeles, where Almena pursued photography and Allison belly danced.

In the early 2000s, when Allison became pregnant with the couple’s first child, they decamped for Mendocino County, where they stayed with one of Almena’s relatives.

Michael Allison said that Almena worked as a marijuana grower, but that he mainly farmed out tasks to other people and didn’t always pay them.

“I never saw any evidence of him being physically violent, but he did a lot of intimidating or threatening,” said Allison, 60, of Portland, Ore., who never warmed to Almena and said he and other relatives repeatedly tried and failed to persuade his daughter to leave him.

By 2013, Almena and Allison had decided to make the warehouse their home. On her Facebook page, Allison called herself the Mother Superior of their artist colony, the Satya Yuga Collective.

The couple advertised the building on Craigslist as a “hybrid museum, sunken pirate ship, shingled funhouse, and guerrilla gallery.”

“Our aesthetic is far from white-wall, so you will simply have to see it for yourself,” read one listing, posted this year. “We are a 24 hour creation space.”

Jay Marsh, 31, moved into the warehouse in August of 2014. “It was kind of exciting at first and then quickly became terrifying,” he said.

Marsh said that on one occasion he witnessed warehouse residents working on the building while under the influence of drugs, including methamphetamine. Hammers pounded on wood for three days without relent, he said.

Parties were frequent. Guests and hosts often were severely intoxicated. Untended cigarettes burned next to piles of old, dry wood.

The place felt like such a fire hazard, Marsh said, that he bought an extinguisher and slept with it next to his bed the entire four months he lived there. During parties, he said, “I would either not come home or stay in my bed hoping nothing caught fire.”

On one occasion, Marsh said he came home to find adults taking drugs while Almena’s two younger children, who were 5 and 3, wandered unsupervised around the warehouse in bare feet. “There was wood with nails sticking out all over the place, it was like a construction site,” he said.

The final straw for Marsh came when Almena became enraged after a dog Marsh was caring for relieved itself on the warehouse floor. “He yelled at me and started punching a wall with a mirror on it,” until his hand bled, Marsh said. “Then he threatened to kill me.”

Marsh said he left before Thanksgiving.

Mariah Benavides, 20, who babysat for the couple’s kids occasionally starting in 2012, said she recalled several instances in which Almena and Allison left her alone with the children for days at a time while they hosted parties at different venues, including a warehouse called Cloud 9.

“I spent a lot of nights there, my mom can attest to that,” she said. “She used to have to come bring me my stuff because I’d be there for so long.”

The couple sometimes paid her in cash, but often tried to compensate her with marijuana, which she said she accepted a few times. Later on, they offered her archery lessons in lieu of money.

“I was like, ‘No, I don’t want that, thank you,’” she recalled.

In 2015, Alameda County Child Protective Services temporarily took Almena and Allison’s children away from them. On her Facebook page, Allison chronicled the steps she and Almena took to convince officials of their parental fitness. They were taking parenting, anger management and domestic violence classes.

Twice a week their urine was tested for drugs, Allison wrote, adding, “We have never tested dirty whatsoever.” Earlier this year, the couple regained custody of their children, an outcome that left some of their relatives flummoxed, Michael Allison said.

The cause of the fire remains under investigation. But officials said they are looking at a refrigerator or another electrical appliance in the warehouse as possible starting points.

When asked during the “Today” interview about his management of the warehouse, Almena, who was standing outside the charred building, described himself as “the father of this space” but did not take responsibility for the fire.

“I didn’t do anything ever in my life that would lead me up to this moment,” he said.

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Paige St. John reported from Oakland and Phillips and Dolan from Los Angeles. Times staff writer Alene Tchekmedyian contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.