The ‘faithless few’: All the times electoral college members voted their own way

There have been a total of 157 faithless voters to date, according to FairVote.org, a nonprofit that advocates for national popular-vote elections for president.

A presidential elector representing Texas declared this week that he would not vote for Donald Trump when the electoral college meets Dec. 19. He is the second Republican elector this year to refuse to cast his vote in accordance with the results in his state.

Christopher Suprun, a paramedic and former firefighter who was one of the first responders on Sept. 11, wrote in a New York Times op-ed that Trump is “someone who shows daily he is not qualified for the office.” Suprun said he had a legal right and constitutional duty to vote his conscience and planned to do so.

Suprun’s announcement followed one by Art Sisneros, another Republican elector in Texas, who last week wrote that he would resign rather than cast his vote for Trump.

Suprun joins a handful of other “faithless electors” in American history. (Since Sisneros resigned, he is not technically “faithless.”)

Samuel Miles of Pennsylvania had the distinction of being the first, in 1796. Miles was a Federalist who had promised to vote for the Federalist candidate, John Adams, but instead cast his vote for Democratic-Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson.

There have been a total of 157 faithless voters to date, according to FairVote.org, a nonprofit that advocates for national popular-vote elections for president.

Several of them broke with the electorate less out of rebellion than for practical reasons. Throughout the years, 71 electors have changed their votes because the candidate their state chose died before the electoral college could convene. In 1872, for example, Democratic nominee Horace Greeley won the general election but died soon after. Sixty-three of the 66 Democratic electors refused to vote for a deceased candidate.

The Constitution does not specifically require electors to cast their votes according to the popular vote in their states, but the laws of 29 states and the District of Columbia bind electors to do so. Some require pledges or threaten fines or criminal action, according to a summary of state laws by the National Assn. of Secretaries of State.

No elector has ever been prosecuted for not voting as pledged.

Since 1900, there have been only nine faithless electors who defected for individual reasons, including one who abstained from voting altogether. Here’s a rundown of who they were and why they did it:

1948

Preston Parks of Tennessee was chosen as an elector for the Democratic Party, which was pledged to incumbent Harry S. Truman. Before the election, some Democrats opposed to Truman’s support of civil rights and racial integration split off and formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party, also known as the Dixiecrats. Parks actively campaigned for Dixiecrat candidate Strom Thurmond and said in advance of the election that he would not vote for Truman under any circumstances, instead voting for Thurmond.

1956

W.F. Turner, a Democratic elector from Alabama, voted for a local circuit judge, Walter E. Jones, for president instead of the Democratic nominee, Adlai Stevenson. Jones, an avowed white supremacist who in 1960 presided over New York Times Co. vs. Sullivan, which later became a landmark Supreme Court case that defined the standard for journalistic libel, was not on the popular ballot. Fellow electors at the time told Turner he was under an “obligation” to vote for Stevenson because the electors had signed a party loyalty oath. Turner replied: “I have fulfilled my obligations to the people of Alabama. I’m talking about the white people.”

1960

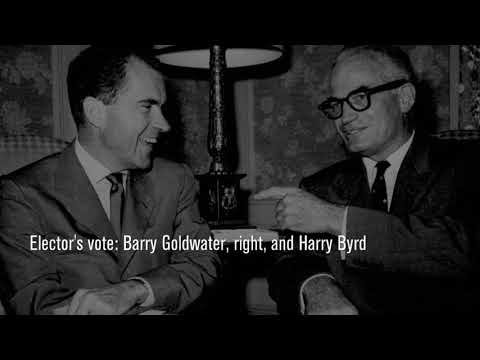

Henry D. Irwin, a Republican from Oklahoma, telegraphed all of his fellow Republican electors in the country asking if they would consider supporting a Barry Goldwater-Harry Byrd ticket over Richard Nixon-Henry Cabot Lodge. Irwin received approximately 40 replies, some favorable, but when it came time to cast their votes, Irwin was the only one who defected. According to an account in the book “Why the Electoral College is Bad for America,” by George C. Edwards III, Irwin told the Senate Judiciary Committee in a subsequent hearing about possibly changing the presidential election procedures that he had worked to get electors to abandon John F. Kennedy and Nixon in favor of a strongly conservative candidate. He said he voted the way he did because he “feared the immediate future of our government under the control of the socialist-labor leadership.”

1968

Lloyd Bailey, a Republican from North Carolina, voted for George Wallace of the American Independence Party over Nixon, the Republican candidate. Bailey was a member of the ultraconservative John Birch Society and, according to Edwards’ book, disliked what he considered to be Nixon’s “leftist” appointments of Henry Kissinger and Daniel Patrick Moynihan to advisory positions, as well as his request to Chief Justice Earl Warren to remain on for an additional six months.

1972

Roger MacBride, a Republican elector from Virginia, deserted Nixon to vote for the candidate of the nascent Libertarian Party, John Hospers, a philosophy professor at USC. MacBride was a political disciple of Rose Lane, according to his obituary in the New York Times. Lane was the daughter of author Laura Ingalls Wilder and an adherent to Ayn Rand’s philosophy of objectivism. After Lane died, MacBride became the guardian of the “Little House on the Prairie” series and produced a television version of it. He went on to become the Libertarian presidential candidate in 1976, but received no electoral college votes.

1976

Mike Padden, a Republican from Washington state, cast his vote for Ronald Reagan (who had lost in the Republican primary) over Gerald Ford, having decided that Ford was not definitively clear in his opposition to abortion. Edwards notes in his book that the 1976 election between Ford and Jimmy Carter was exceptionally close, and had Ford garnered slightly more support, Padden’s faithless vote would have essentially resulted in a tie, throwing the election to the House of Representatives.

1988

Democratic elector Margarette Leach, a nurse and former member of the West Virginia Legislature, voted for vice presidential nominee Lloyd Bentsen as president and presidential nominee Michael Dukakis as vice president. “I wanted to make a statement about the electoral college,” Leach told the New York Times. “We’ve outgrown it. And I wanted to point up what I perceive as a weakness in the system — that 270 people can get together in this country and elect a president, whether he’s on the ballot or not.”

2000

Barbara Lett-Simmons, a Democratic elector from the District of Columbia, left her ballot blank to protest what she called the district’s “colonial status,” or its lack of congressional representation. Lett-Simmons later said she would have voted for Democratic nominee Al Gore if she thought he had a chance of winning. The presidential election that year, between incumbent Vice President Gore and Texas Gov. George W. Bush, was the closest in U.S. history, with 537 votes separating the two candidates in the deciding state of Florida. The narrow margin required a recount and ultimately necessitated a Supreme Court decision. In the end, Bush received 271 electoral votes and Gore 266.

2004

One Minnesota elector voted for vice presidential candidate John Edwards (actually spelled “Ewards” on the ballot) instead of presidential candidate John F. Kerry. That elector also voted for Edwards for vice president. It is not known who it was, since none of the state’s 10 electors identified himself or herself as having cast a protest vote or having made a mistake.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.