From the Archives: Gary Coleman dies at 42; child star of hit sitcom ‘Diff’rent Strokes

- Share via

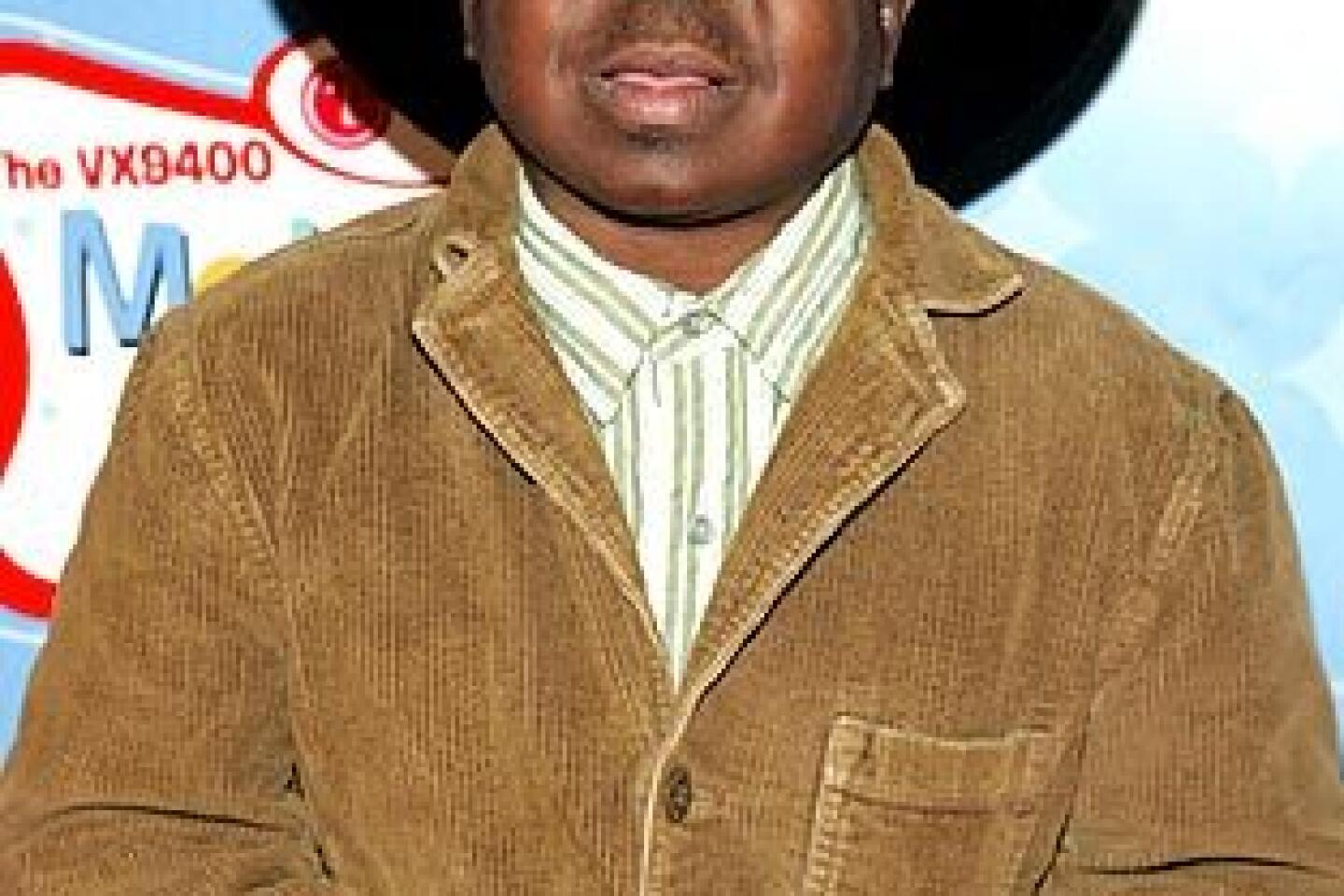

Gary Coleman, who soared to fame in the late 1970s as the child star of the hit sitcom “Diff’rent Strokes” and whose post-TV-series life included a stint as a shopping mall security guard and an unlikely run for California governor, died Friday. He was 42.

The diminutive Coleman, whose adult height was 4 feet 8 inches, died at Utah Valley Regional Medical Center in Provo after suffering a brain hemorrhage earlier this week, according to a statement from hospital spokeswoman Janet Frank.

A resident of Santaquin, Utah, Coleman had been hospitalized Wednesday and lost consciousness the next day. He was taken off life support Friday, the hospital said.

Born with failed kidneys, Coleman had undergone two transplants by age 14 and his growth was permanently stunted by the side effects of dialysis medications.

He was a precocious, chubby-cheeked elementary school student living in Zion, Ill., when a scout for TV producer Norman Lear spotted him in a Chicago bank commercial.

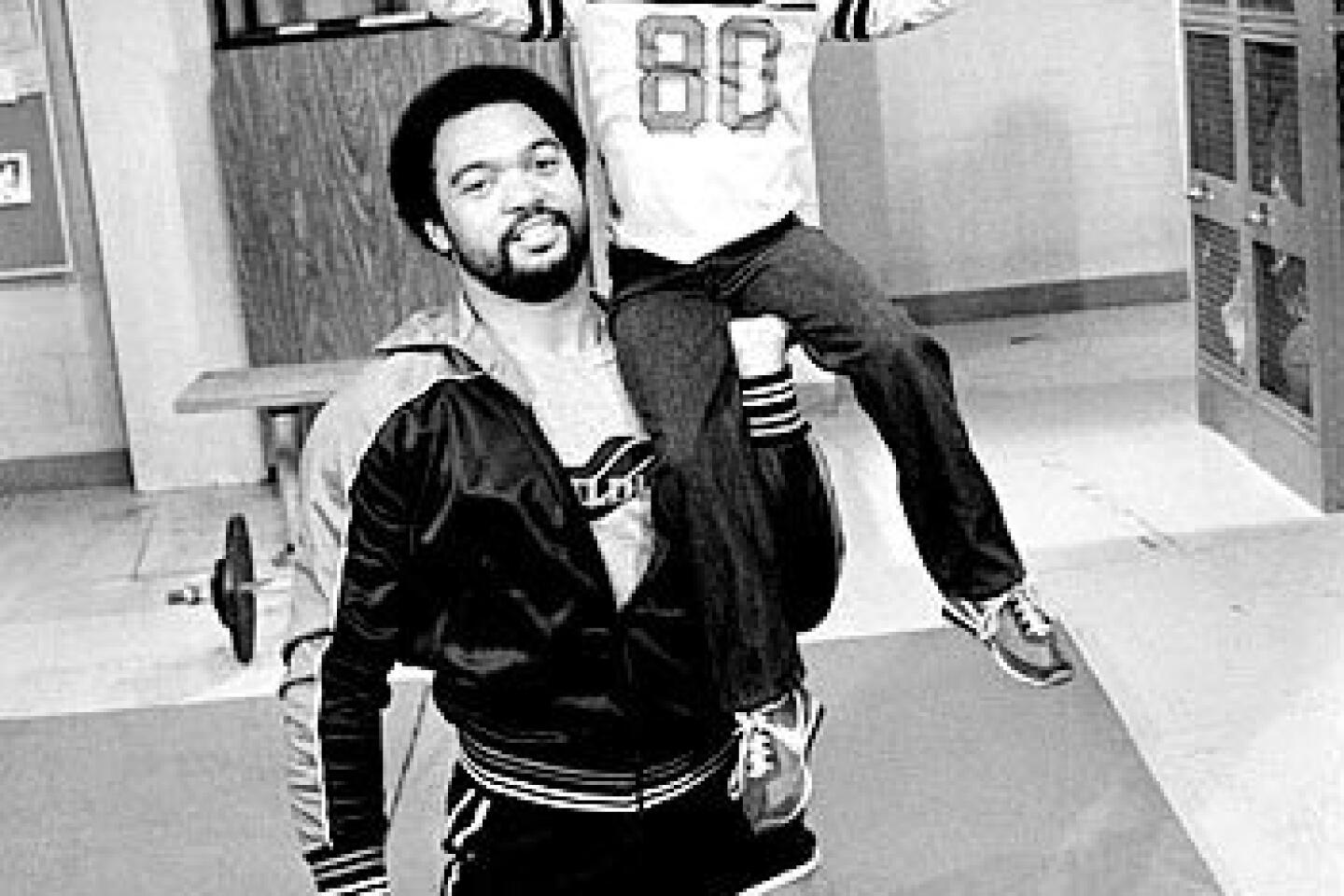

The exceptionally bright, talented and self-confident Coleman was 10 when “Diff’rent Strokes” debuted on NBC in 1978.

As the lovably outspoken 8-year-old Arnold Jackson, he was the comedic centerpiece of the series about two Harlem sons of a black housekeeper whose white boss, a wealthy widower, takes them into his Park Avenue penthouse after her death and later adopts them.

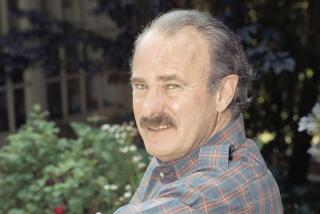

The cast of the sitcom, which ended its eight-season run in 1986 after switching to ABC, included Conrad Bain as the wealthy Philip Drummond; Todd Bridges as Arnold’s older brother, Willis; Dana Plato as Drummond’s daughter, Kimberly; and Charlotte Rae as Mrs. Garrett, Drummond’s new housekeeper.

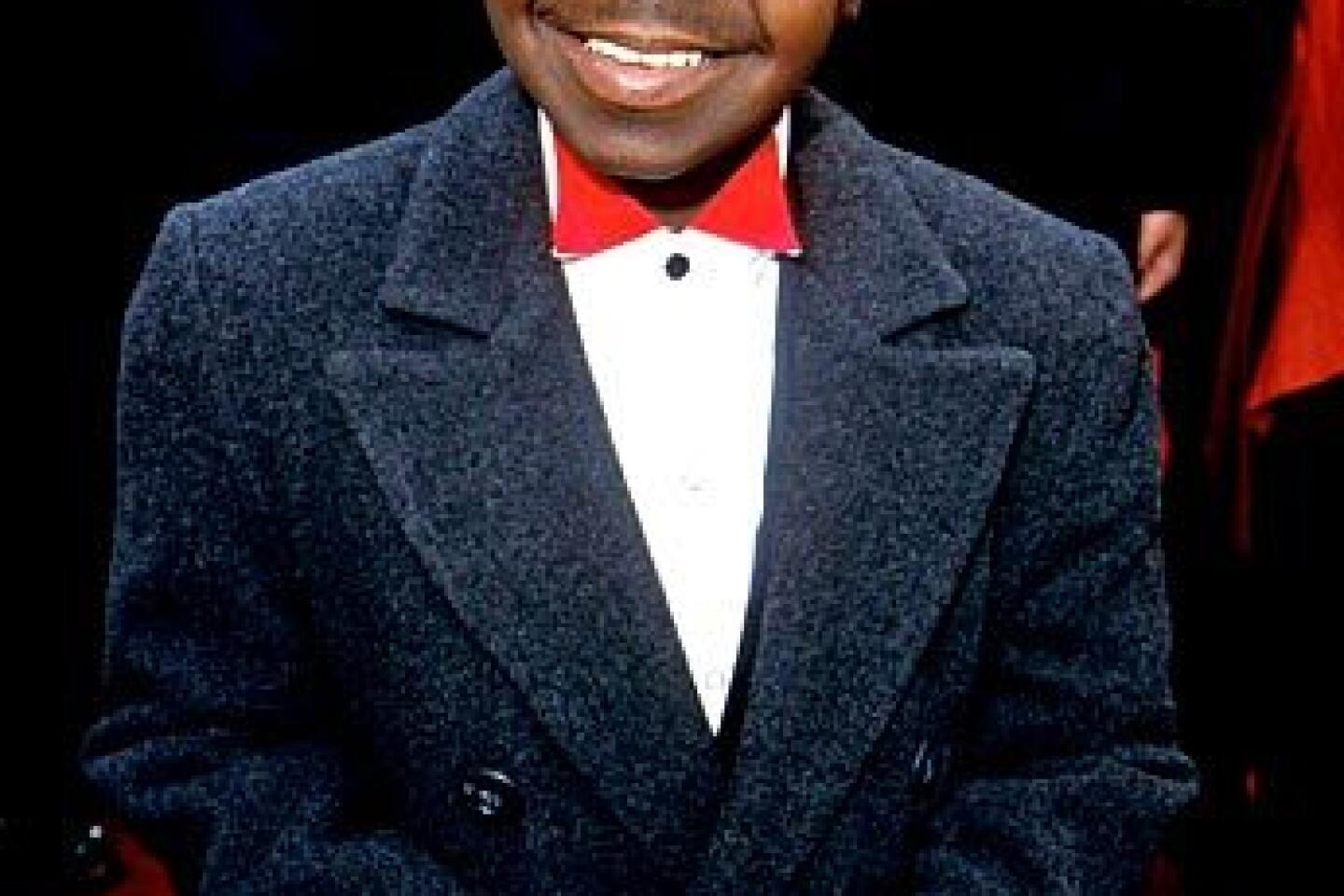

“Its appeal rests chiefly on Gary, a black Pillsbury Doughboy, tiny and cuddly with a face like a pincushion,” The Times’ Howard Rosenberg wrote in 1979. “At 50 pounds and belt-buckle high, he’s small enough to be a Christmas tree ornament. But from his mouth come words … well, you just have to be there.”

In a 1979 TV Guide article headlined “Small Wonder,” Coleman was described as having “the comic delivery” of Jack Benny, Groucho Marx and Richard Pryor.

“When he walks onto a stage, something has happened, and you feel it,” Lear told TV Guide. “That’s called presence, and it’s rare. Many important actors, even stars, don’t have it. Gary does.”

The scene-stealing Coleman quickly became a pop-culture icon, whose recurring line “Whatchoo talkin’ ‘bout, Willis?” became a national catchphrase.

Praised by comedy legends Bob Hope and Lucille Ball, Coleman was in big demand for TV talk shows.

He more than held his own during his first appearance on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” in 1978, which led Carson to jokingly ask his young guest, “What night are you available for guest host?”

At the height of his TV series success, Coleman reportedly earned $64,000 per week and is said to have made $18 million during his TV heyday.

That included income from movies such as “On the Right Track” and “Jimmy the Kid” and TV movies such as “ The Kid With the Broken Halo” and “The Kid With the 200 I.Q.” — as well as the animated series “The Gary Coleman Show.”

Born Feb. 8, 1968, Coleman was the adopted son of W.G. “Willie” and Edmonia Sue Coleman, who, according to a 1990 Times article, brought him home from a Chicago hospital when he was four days old.

It was not until 18 months later, The Times reported, that the Colemans were told that Gary had been born with one atrophied kidney and that the other would soon fail.

In 1989, Coleman sued his parents and his former business manager, Anita DeThomas, for allegedly stealing more than $1 million from him. The Colemans and DeThomas countersued for defamation and breach of contract.

The legal battle ended in 1993 when, Variety reported, a Santa Monica Superior Court judge awarded Gary Coleman $1.28 million and ruled that his parents and manager had wrongfully profited as his guardians and managers during five years while he was a minor.

Coleman’s acting career as an adult fell far short of his “Diff’rent Strokes” glory days. He made only occasional guest appearances and had mostly small roles in films and TV movies.

Coleman, who filed for bankruptcy in 1999, also worked as a commercial pitchman, was hired to have his likeness and voice used in a mature-rated video game and ran a video-game arcade in Marina del Rey, among other things.

The adult Coleman also had a few encounters with the law that put his face back in the news, including allegedly punching an aggressive and much-larger female autograph hunter in the late 1990s, for which he was fined and ordered to take anger-management classes.

In February, he accepted a plea deal in Utah on domestic violence charges stemming from an incident the previous year between him and his wife, Shannon Price. Coleman was fined $595 and ordered to take classes on avoiding domestic violence.

Coleman’s profile as a “former child star” reached its peak in 2003, the year he gave permission to a Bay Area alternative weekly newspaper to jokingly nominate him for governor in California’s gubernatorial recall election.

He was among 135 candidates in the election, a colorful field that included L.A. billboard queen Angelyne, comedian Gallagher, Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt and porn star Mary “Mary Carey” Cook.

A New York Times writer wrote that Coleman “had become the poster child of the California freak show that is the governor’s recall election.”

Coleman, the Washington Post reported, “has walked a line of believing in his own legitimacy and mocking it.”

“My slogan,” Coleman told the Post, “is I’m the least qualified guy for the job, but I’d probably do the best job.”

Coleman, an independent who later appeared on CNN to say he was endorsing fellow actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, received 12,683 votes, placing eighth in the race that saw Schwarzenegger elected.

“I want to escape that legacy of Arnold Jackson,” Coleman told the New York Times during his run. “I’m someone more. It would be nice if the world thought of me as something more.”

Coleman is survived by his wife and parents.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.