Ed Edelman, crusading L.A. County supervisor, dead at 85

Ed Edelman, the longtime Los Angeles County supervisor whose crusading policymaking influenced many aspects of local life including child welfare, health services and environmental preservation, has died. He was 85.

During his 20 years on the Board of Supervisors, Edelman championed efforts to improve the way county government treated its most vulnerable citizens while also fighting to protects parts of the Santa Monica Mountains from development.

Edelman, a Democrat who represented some of the county’s wealthiest communities such as Brentwood and Bel Air, died Monday at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Westwood, according to his wife, Mari Mayer Edelman. The cause was complications from atypical Parkinson’s disease, she said.

“He declined steadily,” she said, calling his death a long goodbye during a years-long illness. “We had a home filled with people and music and love. … You couldn’t help but love this man. He cared so much about other people.”

Edelman’s lawyerly approach to governance often left him overshadowed by more colorful colleagues on the five-member board, but his manner was ideal for the behind-the-scenes consensus-building that became the signature of his tenure. As one of the most liberal members of a board that was often dominated by conservatives, Edelman needed strong negotiating skills to get his projects approved. The county AIDS Program, a children’s dependency court, a revamped Department of Children’s Services and the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority were all pushed by Edelman.

Over the years he also played a key role in resolving several labor conflicts, including a threatened walkout by county nurses in 1990 and a Metropolitan Transportation Authority strike in 1994.

In a territory as large as some nations and a budget in the billions, Edelman was the understated statesman with a genteel voice. He was described as cautious and deliberative, but sometimes bland.

“I’ve never been a grandstander,” Edelman told The Times in 1993. “Getting the votes is what counts.”

Edmund D. Edelman was born Sept. 27, 1930, in Los Angeles, grew up on the Westside, was educated in city schools and served in the Navy after high school. In 1954 he graduated from UCLA with a bachelor’s degree in political science and four years later earned a law degree. After law school Edelman taught at Fairfax High School’s evening school, served as a staff lawyer for a congressional subcommittee on education and labor, and from 1963 to 1964 worked as a special assistant to the general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board in Washington, D.C.

Edelman’s life as an elected official began in 1965 after a race against a well-established incumbent, Rosalind W. Wyman, for the seat representing the city’s 5th Council District. Wyman, only the second woman to be elected to the City Council, was a political opponent of then-Mayor Sam Yorty, who launched a campaign against her and supported Edelman.

Wyman was forced into a runoff, and voters handed Edelman a decisive victory. His celebration was muted by the death of his father on the same day.

After nine years on the Los Angeles City Council, Edelman made a run for a seat on the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors in a bitter contest against John Ferraro, who was also a city councilman.

During the campaign Edelman sounded less like a conciliator and more like a rebel. He launched his campaign against “the Establishment” in East Los Angeles because the board had failed to address the community’s needs.

“County government in my opinion is probably one of the least responsive, probably one of the most corrupt of any level of government existing in the state of California, or indeed throughout this country,” he told The Times in April 1974. “... It’s going to be a long, tough campaign because we’re running against the Establishment.”

Edelman won the seat and took office with a list of goals that included expanding the board from five members to seven members, which he did not achieve, and making county government more responsive to human needs, such as juvenile justice, drug addiction and welfare — a goal many would say he accomplished.

“Power must be used properly,” Edelman said in 1974. “The system must be changed constructively. ... I will concentrate on human needs.”

After winning that campaign, Edelman went on to champion many causes. In the Hall of Administration the running joke was that his greatest contribution was Pasqua’s, an upscale sandwich shop for which he lobbied.

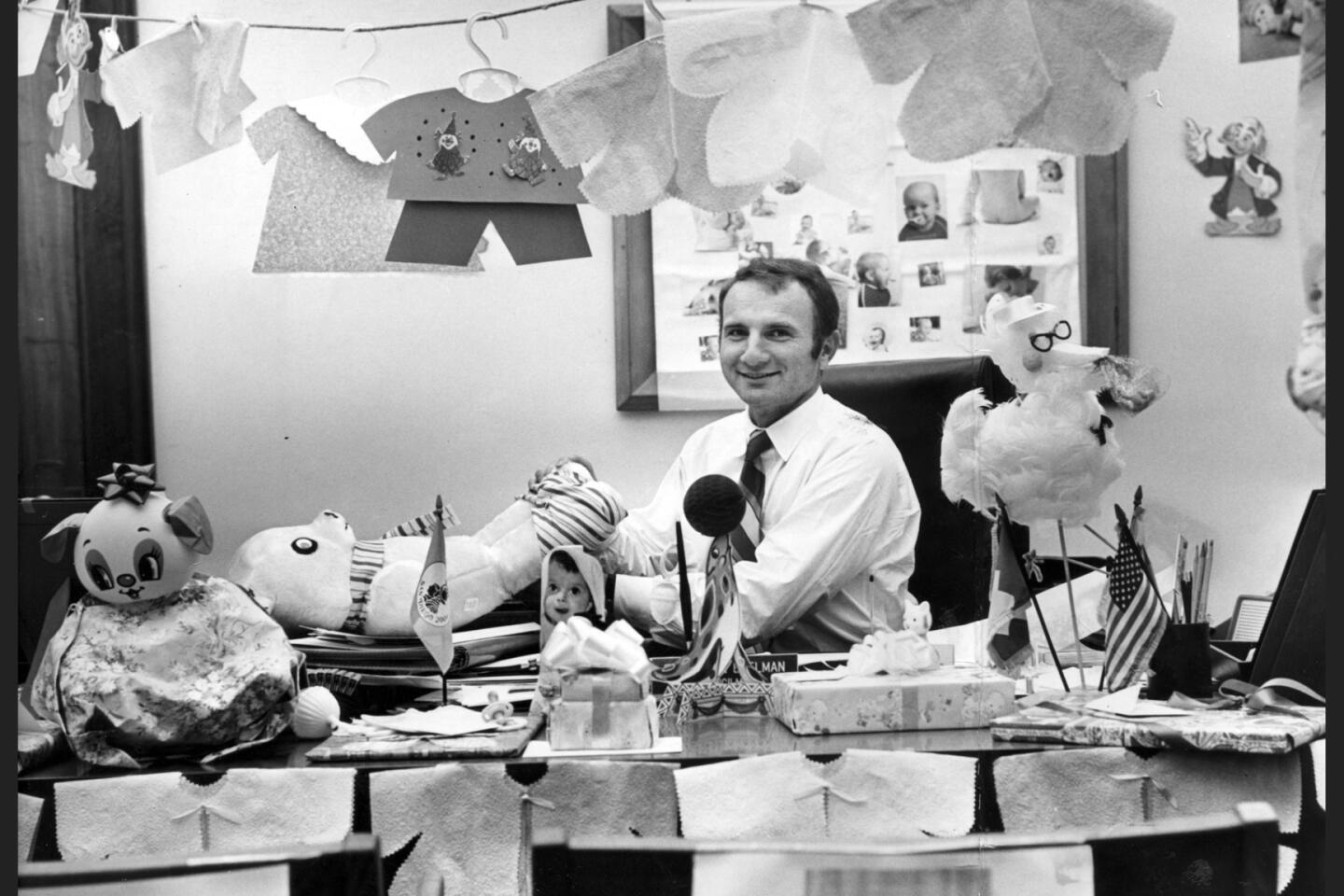

The Monterey Park facility known as the Edmund D. Edelman Children’s Court was also championed by Edelman. The facility, which houses numerous courts, was designed to be more sensitive to the needs of neglected and abused children.

A fervent supporter of arts and culture, Edelman played an important role in the renovation of the Hollywood Bowl, plans for the construction of Walt Disney Concert Hall and the creation of the Hollywood Bowl Museum, which was renamed in tribute to him in 1996.

Some of his critics accused Edelman of pandering to the Westside, while ignoring the needs of East Los Angeles, a charge Edelman and some of his Eastside supporters rejected.

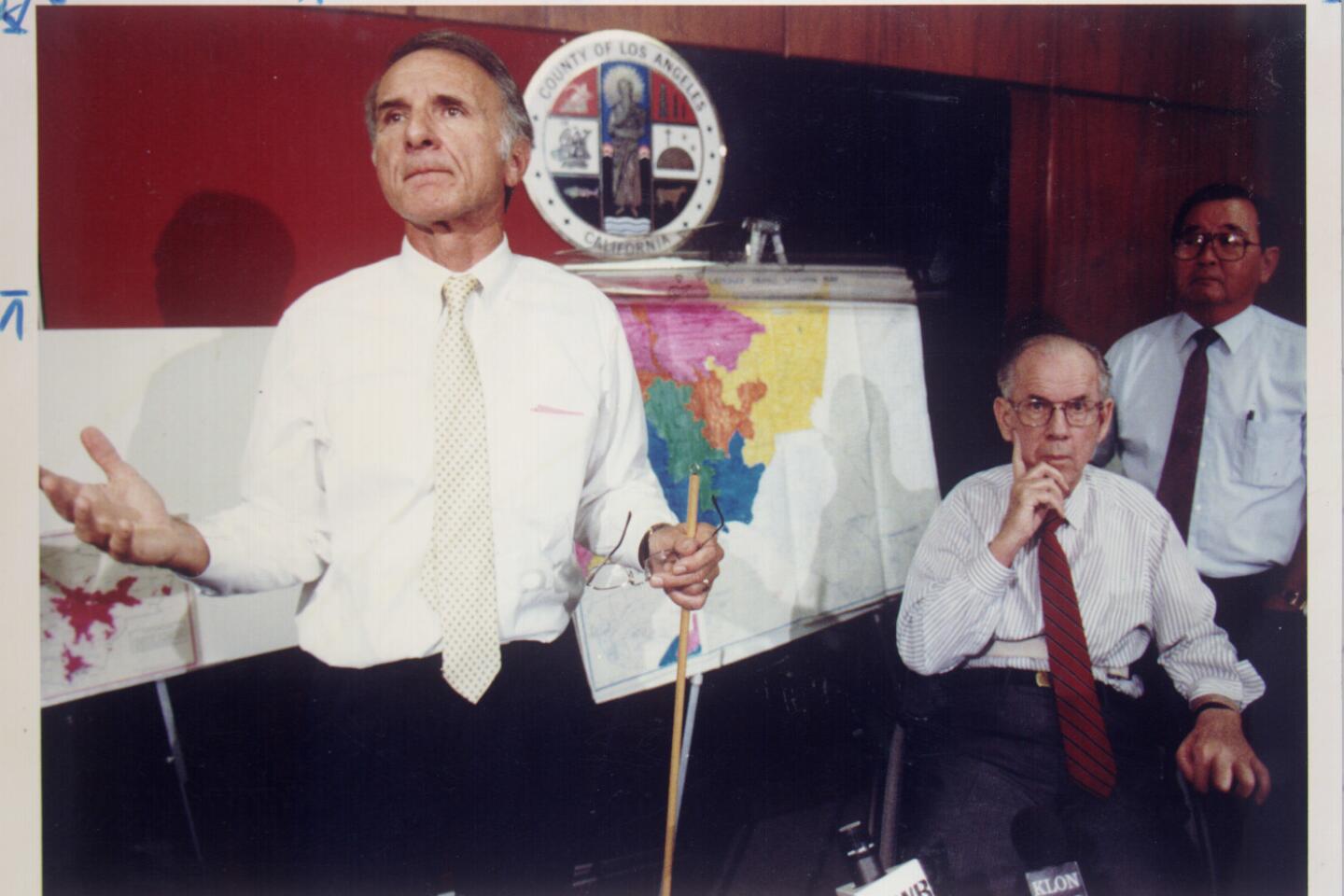

Perhaps the ugliest episode of Edelman’s tenure occurred during a redistricting effort that ultimately led to the creation of a Latino-dominated district in East Los Angeles. In 1990 Edelman testified in a voting rights trial brought after civil rights advocates accused the Board of Supervisors of weakening the voting power of the county’s then 2 million Latino voters by dividing them among three districts.

Edelman opposed a plan to increase the number of Latinos in his district and was cast as a civil rights foe. He testified that his position mirrored that of a Latino political group that “objected to lumping all of the Hispanics into one district” and called criticism of his position as “political hype.”

“It was important to have minorities not lumped into one or two districts but have influence in other districts,” Edelman said in a 1990 Times article.

A federal judge ruled that board members had intentionally discriminated against Latinos to protect their own political offices.

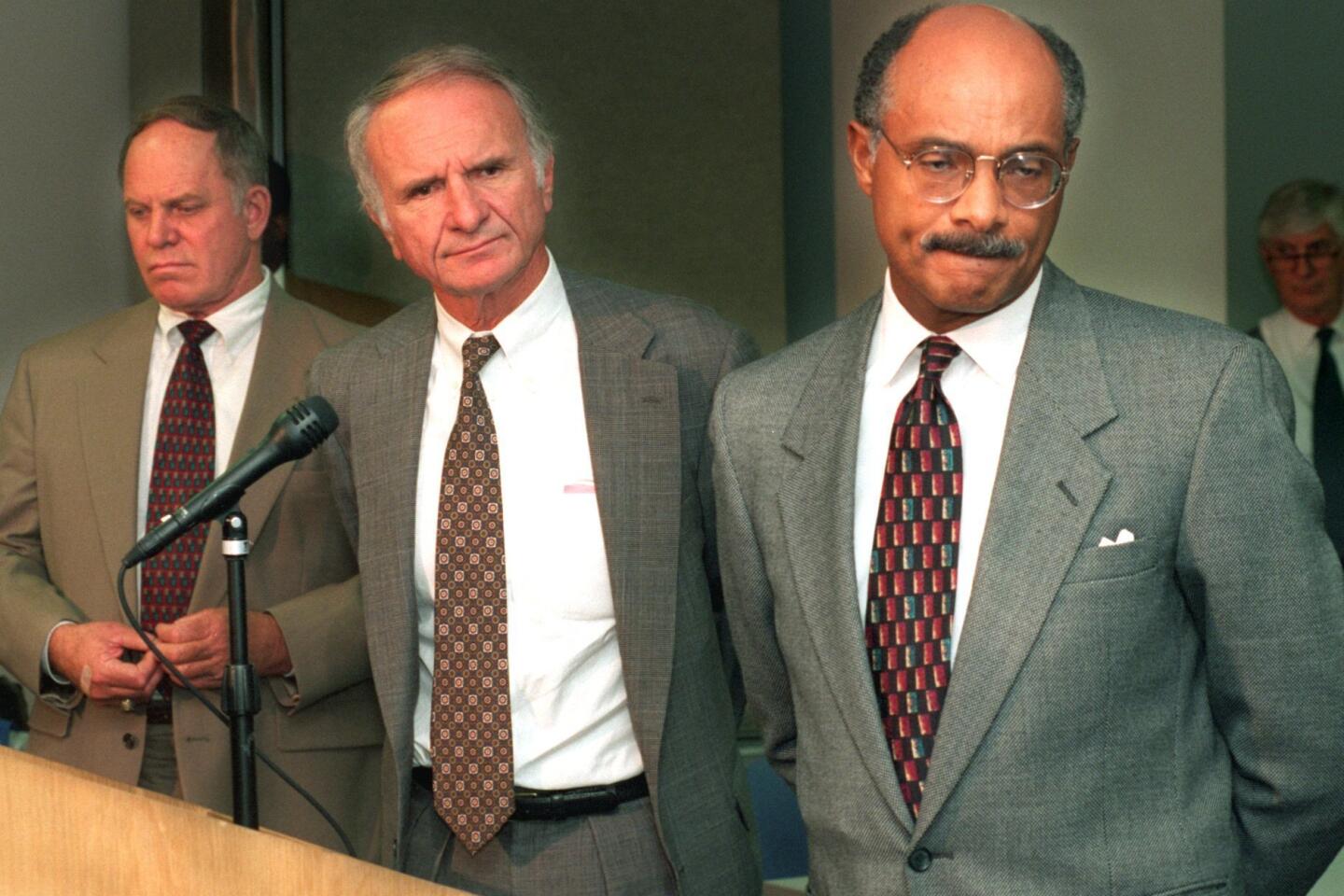

The suit resulted in reapportionment that brought Supervisor Gloria Molina to the board, and created a liberal majority. Redistricting also added a piece of coastline, stretching from Malibu to Venice, to Edelman’s district and added environmentalism to his top list of concerns.

In 1994 the Santa Monica Conservancy named 257 hillside acres the Summit Valley Edmund D. Edelman. It pays tribute to Edelman for helping forge a deal between the conservancy and developers who had planned to build luxury homes and a golf course on the land.

During his time on the board Edelman witnessed a shift from a conservative majority to a liberal majority. Liberals gained a voting advantage but then faced another problem.

“There is a liberal majority but no money to be liberal with; I now have to be the conservative,” Edelman said in a 1994 Times interview.

By 1994, the year he retired, Edelman had started to see more and more of his programs “threatened by budget crunches,” he said in the article.

“The fiscal situation is dark ... and I don’t know whether I want to subject myself to that kind of pain again for another four years.”

After retiring from the board, Edelman worked as a negotiator at Judicial Arbitration & Mediation Services/Endispute based in Orange, and as a senior fellow and assistant to graduate students at the Rand Corp. Later he was hired by the city of Santa Monica to tackle the homelessness problem. During his tenure Edelman oversaw the creation of the Santa Monica Homeless Community Court, a program designed to use the justice system to link homeless people with social services. Edelman also negotiated with those who provided food to the homeless to serve them indoors instead of at a local park.

“There’s a lot of issues when you’re out of office you wish you could bring a resolution to, and the complex problem of homelessness is at the top of the list,” Edelman said in a 2006 article in The LookOut News.

In 1968, Edelman married Mari Mayer Edelman, a psychologist. The couple had two children, Erica and Emily, and four grandchildren.

Stewart is a former Times staff writer.

ALSO

Stanley Sheinbaum, L.A. liberal lion who shaped decades of political dialogue, dead at 96

Greta Friedman, woman in iconic WWII Times Square kiss photograph, dies at 92

Prince Buster, Jamaican music legend who pioneered ska music, dies at 78

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.