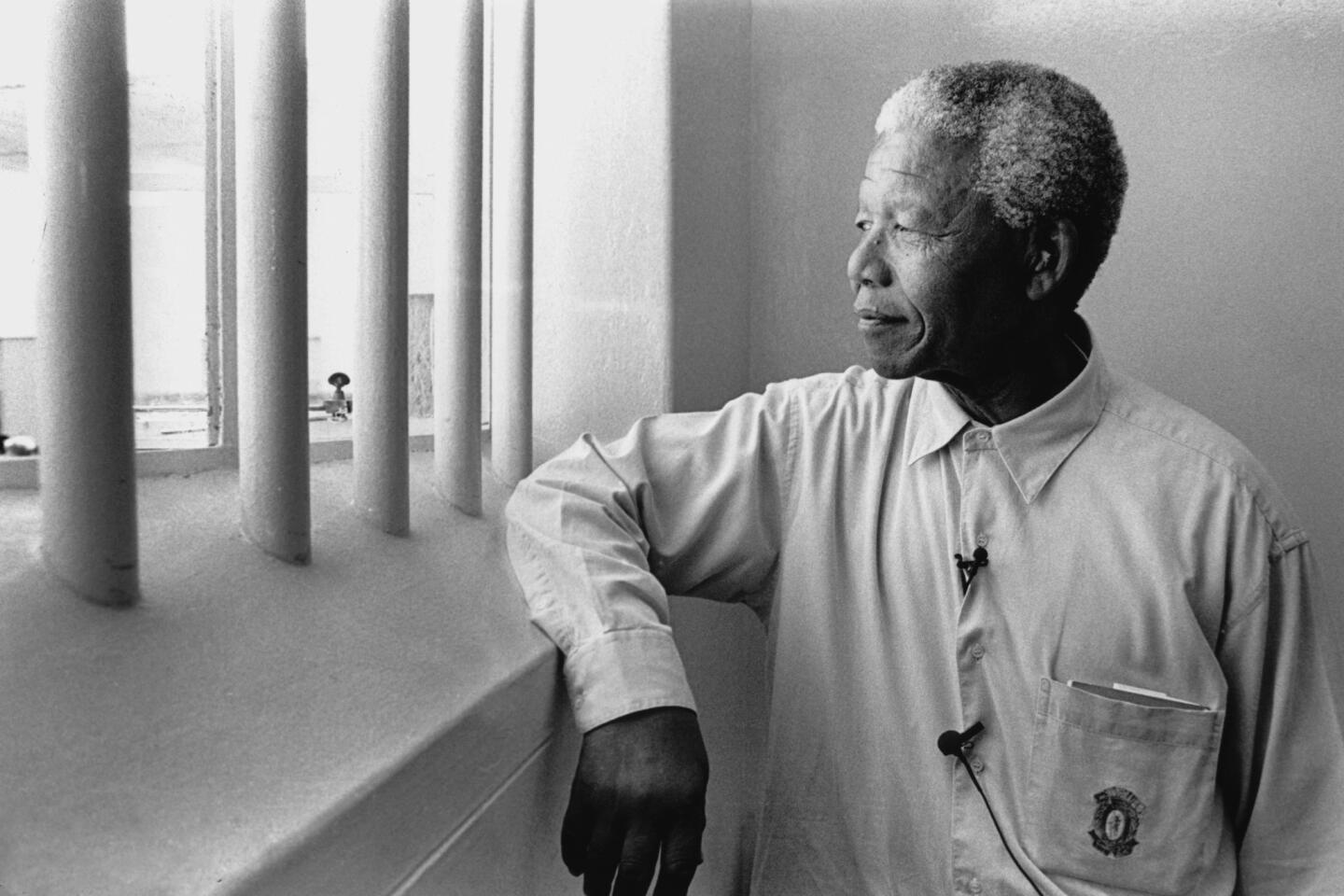

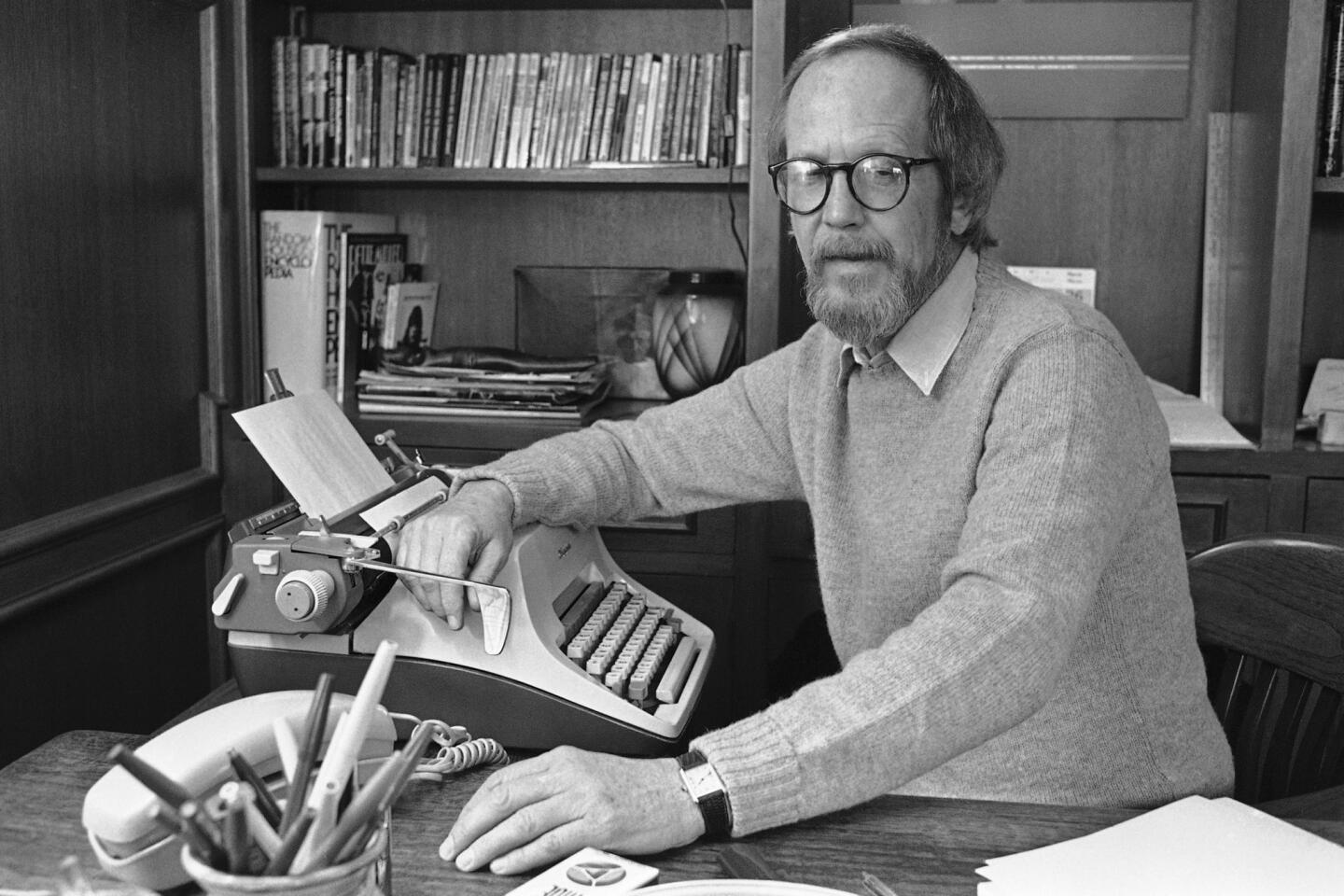

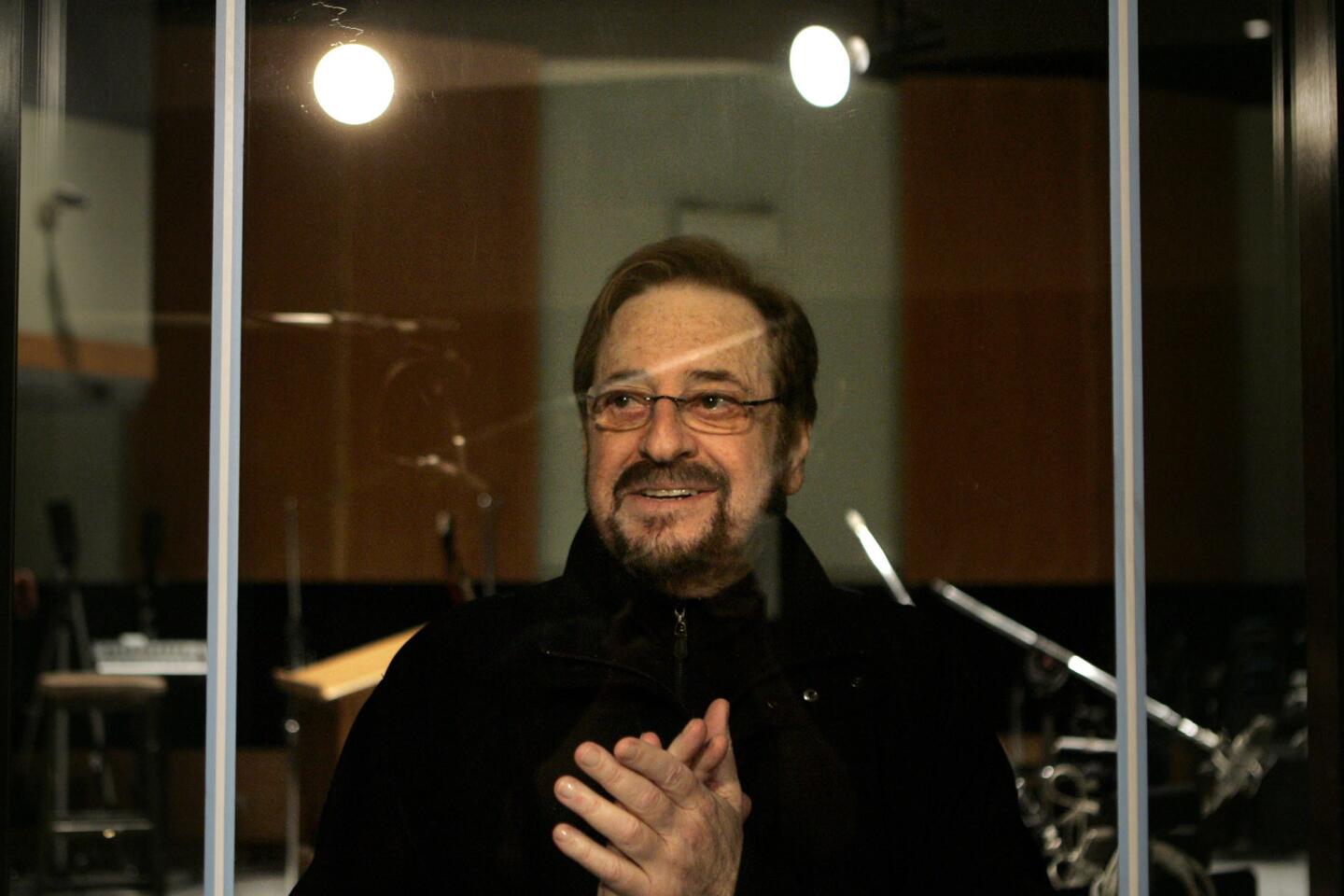

Donald Richie dies at 88; interpreted Japan for the West

- Share via

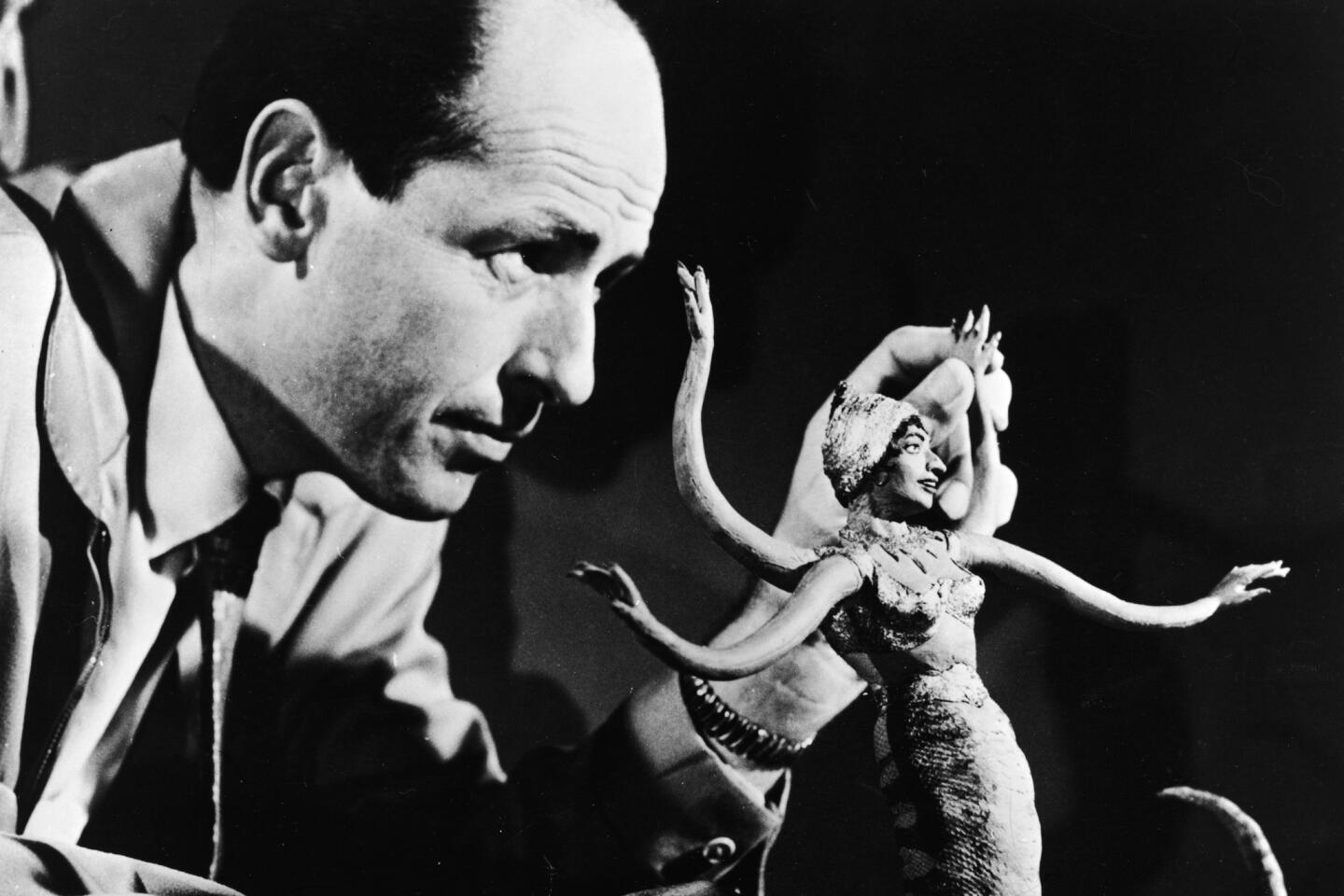

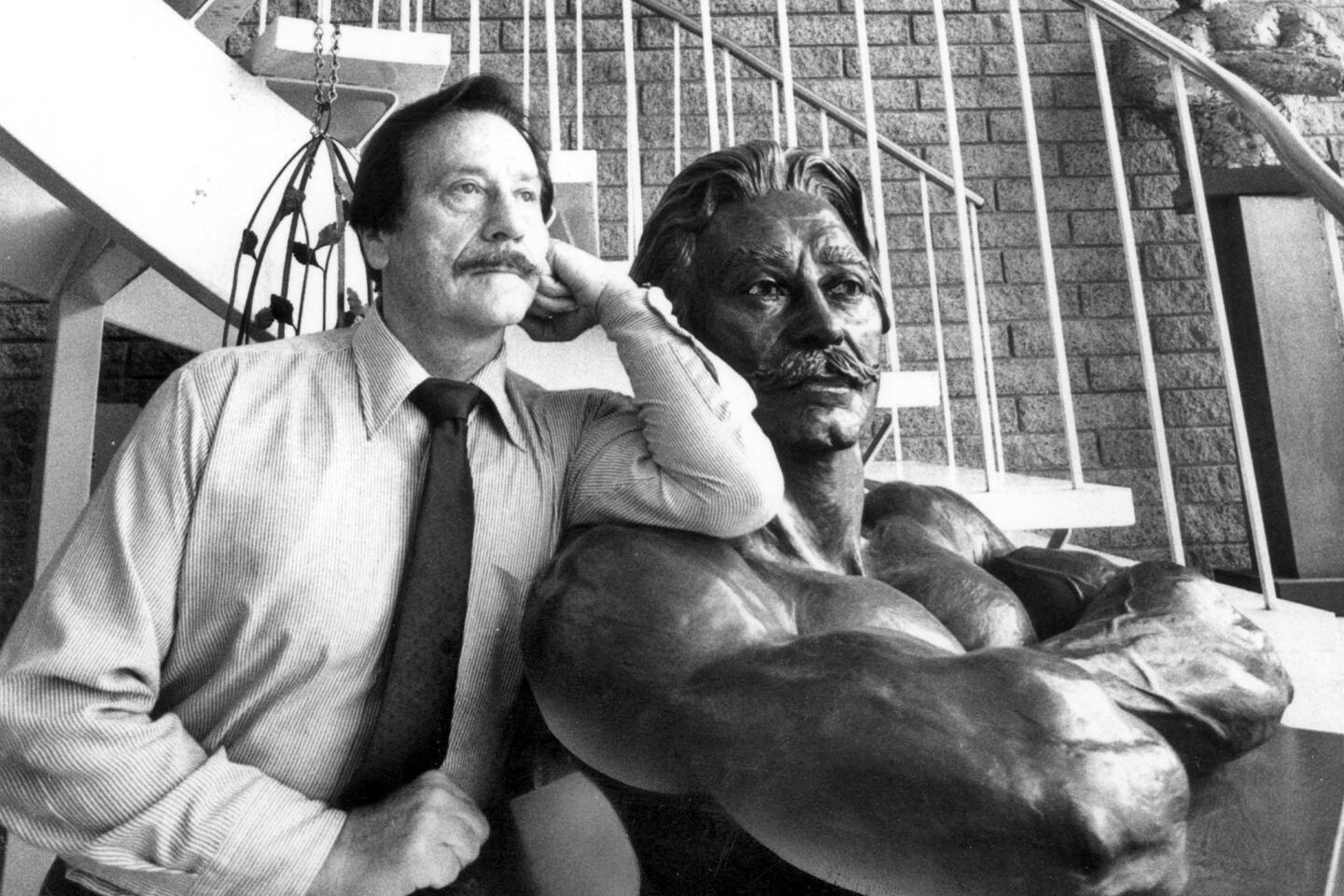

Donald Richie, an American expatriate in Japan who became that country’s preeminent Western interpreter, explaining its culture — from cinema to Zen to tattoos — in books and essays that illuminated the author’s psyche as much as that of his adopted home, has died. He was 88.

Richie, who lived in Japan for more than 50 years, died Tuesday in Tokyo after a series of small strokes and other ailments, said his longtime friend Christopher Blasdel.

An Ohio native, Richie discovered Japan in the early years of its struggle to recover from the devastation of World War II. He found a unique freedom there as a gaijin, or foreigner, who, he wrote, “could be expected to know nothing.”

Movies became his portal into understanding Japanese culture and his place in it. His 1959 book “The Japanese Film: Art and Industry,” co-written with Joseph L. Anderson, established him as an authority on Japanese cinema. His later works on directors Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu were instrumental in introducing their films to Western audiences in the 1960s and ‘70s.

From there Richie evolved into a perceptive cultural commentator. “Everyone who writes on the place writes in his shadow and his debt,” Pico Iyer, the British-born travel writer and novelist who has spent considerable time in Japan, once wrote.

Richie’s work appeared in nearly every major English-language publication, including Newsweek, Time, the Wall Street Journal and the Atlantic Monthly. He produced more than 30 books, including historical novels, a classic travelogue called “The Inland Sea” (1971), “The Donald Richie Reader” (2001) and the autobiographical “The Japan Journals” (2004).

His topics ranged from the arcane, such as the history of Japanese tattoos, to the mundane, such as subway etiquette. Little was taboo: A bisexual who gravitated toward men, he wrote freely about sexuality, including his own, and described in often sensual terms Japanese festivals and rituals unfamiliar to most Westerners.

His subtext was almost always personal.

“One Way to Eat,” an essay from “The Inland Sea,” begins in a Hiroshima restaurant with the author drawing unpleasant stares by eating giant prawns with his fingers instead of chopsticks. The piece moves from there to deeper topics: the disapproval inherent in a Japanese phrase for “you’re welcome,” the Japanese resentment of Chinese and Koreans, and the stigmatization of all foreigners, including this apparently ugly American.

“I want to find the place where the real Japanese live,” he wrote, explaining what he had thought was his reason for exploring the Japan beyond Tokyo. “Is not what I really want a place where I can find my own individuality?”

“I am looking for a land where people will accept me: I am not looking, as I had thought, for a land where I could accept them.”

Richie “gave Japan the gift of astute observation. Japan,” his friend and editor Leza Lowitz told The Times last week, “gave Richie the gift of self-discovery.”

Donald Steiner Richie was born April 17, 1924, in the northwest Ohio town of Lima. His father, Kent, owned the Lima Radio Parts Co. and his mother, Ona, was a homemaker.

The defining event of his youth was seeing the Orson Welles film “Citizen Kane” in 1941. “He raced up to the bedroom and he said, ‘My eyes are open.’ It really changed his life,” recalled his sister, Jean Reuther of Loma Linda, who is his only survivor. “He thought movies were just glorious stories, but this opened his eyes to the possibilities of movie-making.”

Lima held few other attractions for him, so, as he later wrote, “my first ambition was to leave.” After finishing high school, the 17-year-old hitchhiked to New Orleans, where he stayed several months. Then, with the outbreak of World War II, he joined the merchant marines, which took him to northern Africa, southern Europe and China.

On the first day of 1947, he arrived in Japan. He worked as a typist for the U.S. occupation forces before finding a more satisfying job as a staff writer for the Army newspaper Pacific Stars and Stripes. Fraternization between Americans and Japanese was severely restricted, but Richie found a legitimate way to slip free: He became the newspaper’s movie reviewer.

“For me,” he told the New York Times in 2001, “movies became the preferred way of life, and when I wanted to get to know Japan I had to know its movies. That’s where the secrets are.”

He returned to the U.S. in 1949 to attend Columbia University, graduating in 1953 with a bachelor’s degree in English. In 1954 he headed back to Japan and became a film critic for the English-language Japan Times.

His 1959 book, “The Japanese Film,” brought him international prominence and famous visitors who sought him as their guide. His journals are studded with anecdotes about his encounters with luminaries such as Truman Capote, Alberto Moravia, Igor Stravinsky and Francis Ford Coppola. He also wrote about his friendships with Japanese figures such as novelist Yukio Mishima, actor Toshiro Mifune and Zen philosopher D.T. Suzuki.

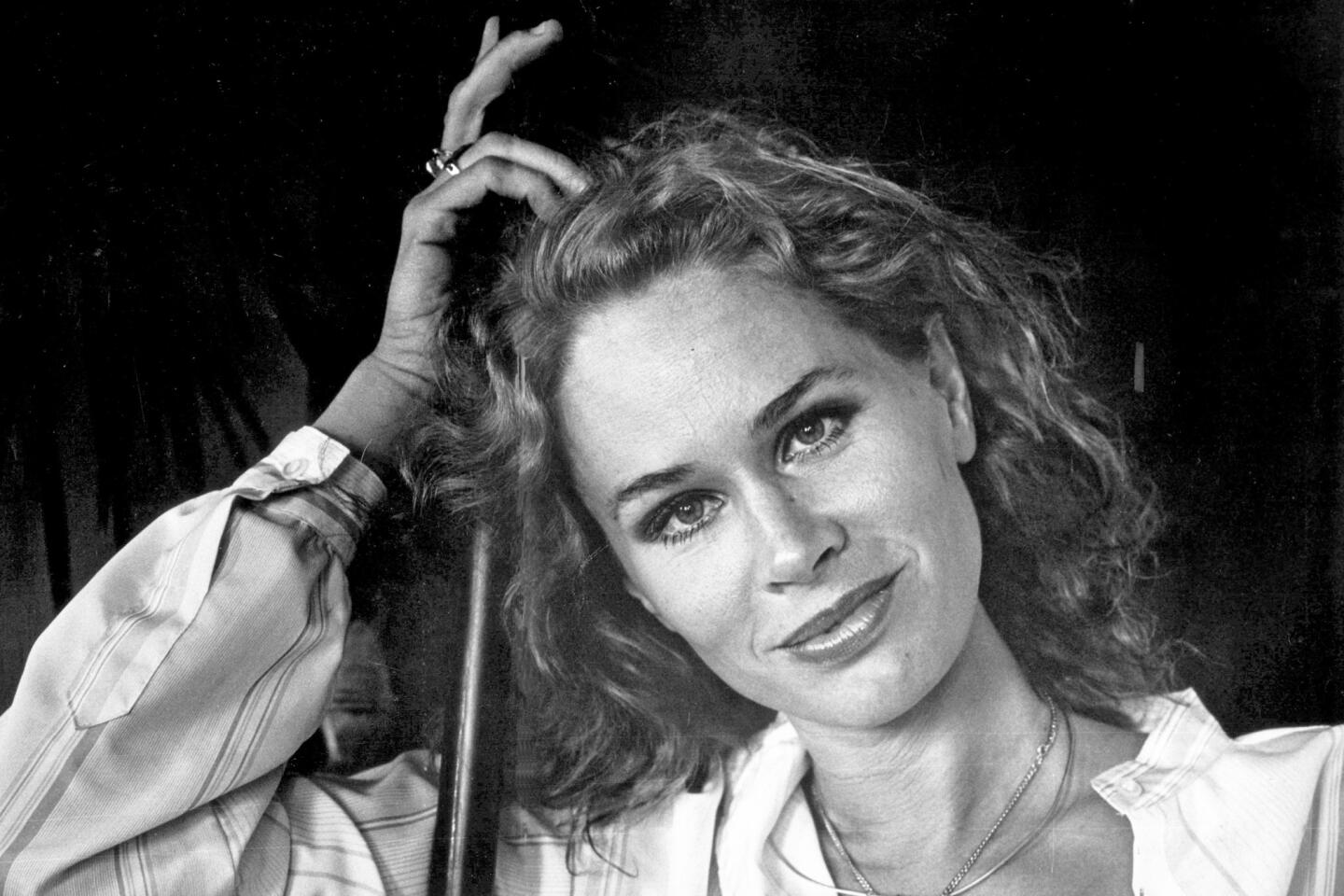

He married writer Mary Evans in 1961; they divorced in 1965.

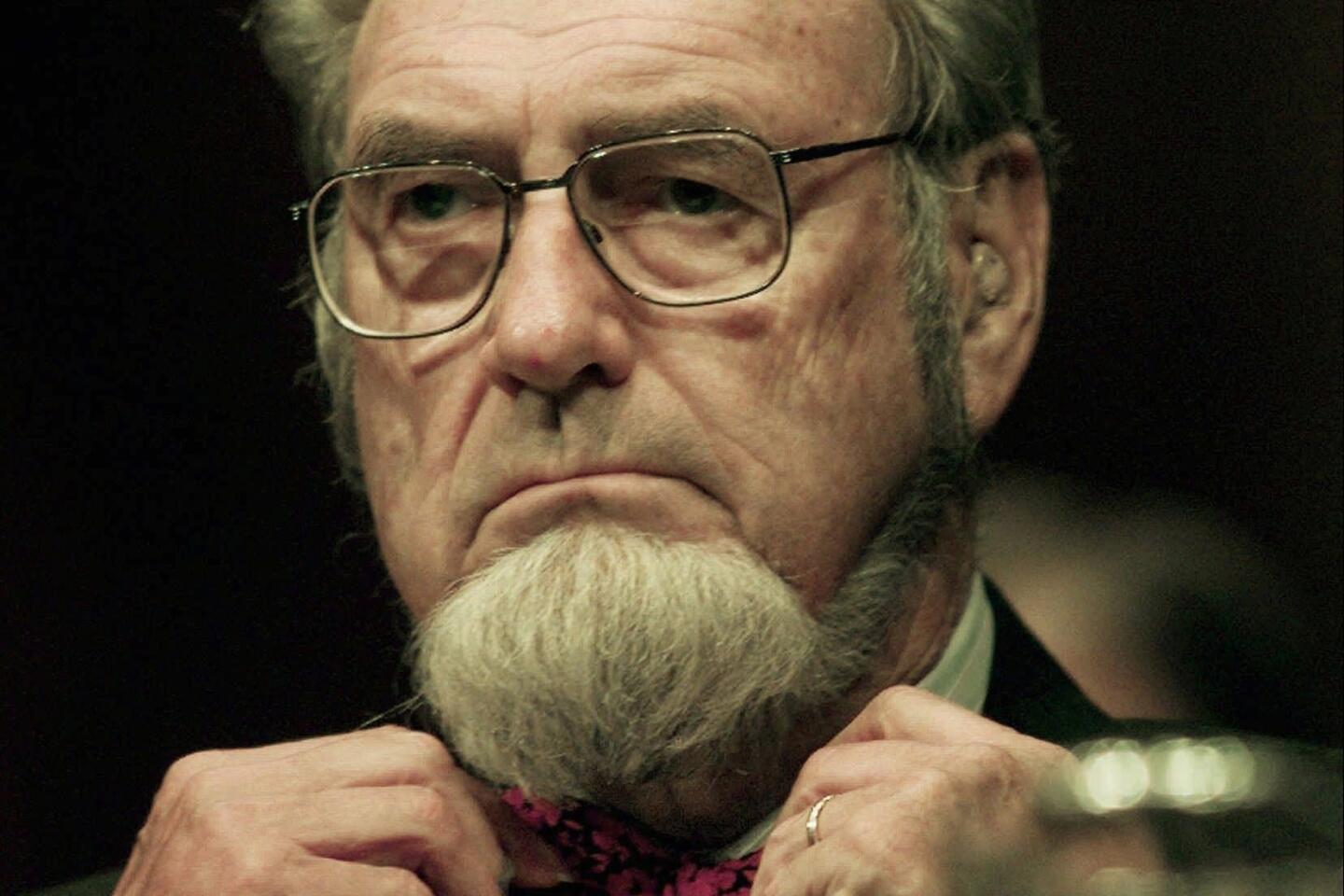

Aside from college, Richie’s only lengthy absence from Japan was the four years he spent as curator of film at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, from 1968 to 1972. He returned each summer to Japan because America, he wrote, “was just one big Ohio so far as I was concerned.”

For Richie, nothing was more fulfilling than being the stranger in a strange land.

“In Japan, I sit on the lonely heights of my own peculiarities and gaze back at the flat plains of Ohio, whose quaint folkways no longer have any power over me, and then turn and gaze at the islands of Japan,” he wrote in 1993, “whose quaint folkways are equally powerless in that the folk insist that I am no part of them. This I regard as the best seat in the house because from here I can compare, and comparison is the first step toward understanding.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.