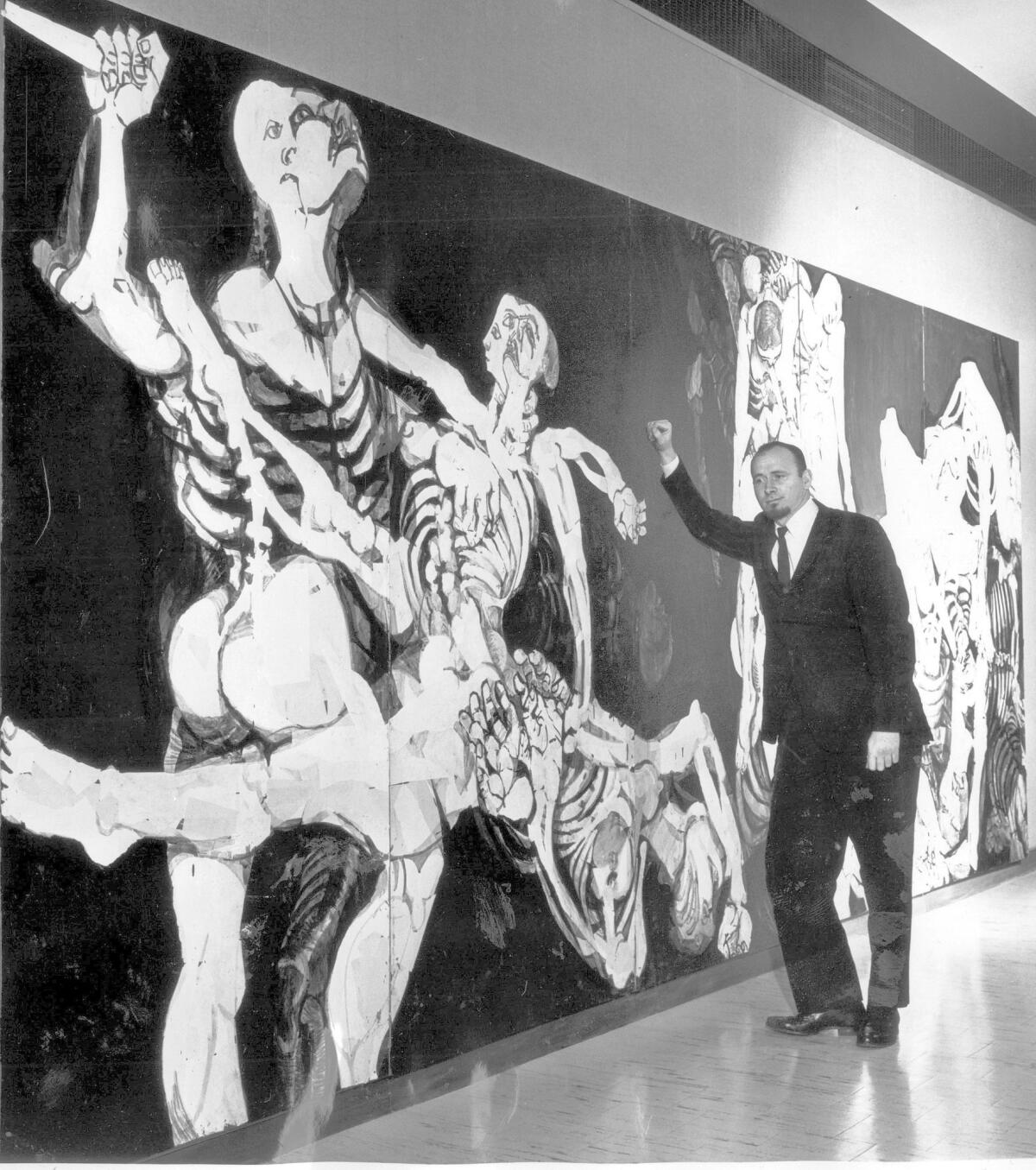

Connor Everts dies at 88; artist’s work was focus of 1960s obscenity trial

- Share via

Connor Everts, a Los Angeles-area artist and former longshoreman whose sociopolitical art was the subject of a 1960s obscenity trial, died Sunday at his Torrance home. He was 88.

The cause was not disclosed.

Everts completed his early work at night after working full days on the docks. His career was punctuated by jaunts abroad and by controversy: In 1964, sheriff’s deputies arrested him for having produced a poster displayed in a store window on La Cienega Boulevard.

They said its depiction of a womb and face was a violation of state obscenity laws.

The ensuing court case became a local cause celebre as fellow artists and progressives rallied to Everts’ side. A Times’ art critic testified in his defense, as well as various other curators and experts.

On the stand, these defenders of art freedom uniformly struggled to explain to prosecutors why Everts’ womb image — intended as a commentary on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy — was not an outrage to public decency, as prosecutors argued it was.

Be more specific, the judge admonished.

They couldn’t, the witnesses said — art is intangible.

The case grabbed headlines for months. But even at the time, it was portrayed as a kind of last gasp of an old order. Hardly anyone was being tried for obscenity by that point, and contemporary observers seemed to recognize that situation was not likely to change.

The jury hung, and Everts was later acquitted.

He again made headlines a couple of years later. He was arrested and said he had been beaten by two Long Beach police officers. They were, in turn, tried and acquitted.

Otherwise, he settled into his role as an art teacher with a loyal following and kept producing art.

The notoriety of Everts’ trial had drawn well-known artists to his side. His connections made him well-placed to become a supporter and promoter of fellow artists locally.

The whole episode — and his role in the local art scene — continued to play an outsized role in reputation, even to the point of eclipsing his art. “Sometimes an artist’s major aesthetic achievement is his life,” wrote Times critic William Wilson, commenting on an Everts show in 1969.

“He was authentic,” said his wife of 20 years, Judy Colman Everts. “If he didn’t like you, you knew about it, and ... if he did, he took you into his heart forever.”

His students “either hated him or worshiped him,” she added.

Everts was born in Bellingham, Wash., Jan. 24, 1928, to William and Sophie Everts. His father was a longshoreman and union organizer, and the younger Everts would follow his example — both in dock work and in leftist sympathies.

He served in the Coast Guard during World War II and studied art in L.A. at Chouinard Art Institute. He traveled and studied in Latin America and was an assistant to Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siquieros.

He returned to L.A. and worked as a longshoreman to support his wife and children, and painted at night. “I’d rather paint than sleep,” he told a reporter.

He soon joined the graphics department at Chouinard, but lost the job after the womb-image flap.

The image was part of a series of nine lithographs he had titled “Studies of Desperation.” In the aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination, the works explored the theme of a person looking out from the womb and choosing not to be born, he said.

In 1966, he was arrested again while celebrating in a bar with students, and said police had beaten him, causing permanent injury to one hand.

An officer denied this, saying he had struck Everts once on the leg on the way to the station to stop his kicking in the patrol car. In a 12-day trial in federal court on civil-rights charges in 1968, the officer and his partner were acquitted.

The Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery mounted a retrospective of his work in 1983, and Everts’ work was included in the Getty’s “Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980.”

“Studies in Desperation” was the subject of a 2013 Norton Simon Museum exhibition, and Everts’ work is part of collections in, among others, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Norton Simon and the Smithsonian Institution.

He co-founded the Los Angeles Printmaking Society, created the now-defunct Exodus Group and Gallery in San Pedro, taught at the San Francisco Art Institute, USC and Caltech, and traveled to Japan and Europe.

Everts’ art, post-trial, was “technically inept” though “shot through with the ungainly passion of dedication,” the Times’ Wilson opined.

But another Times critic, Henry J. Seldis, praised Everts’ “landscapes of the mind set in a quasi-mathematical framework.”

Everts testified in his own defense at the trial, countering the accusation that he had made pornography. “I came up with something beautiful if one concerns himself with truth,” he said.

MORE OBITUARIES

Walter Kohn dies at 93; UC Santa Barbara physicist shared Nobel Prize in chemistry

Willie Williams, Los Angeles police chief after the 1992 riots, dies at age 72

Steve Julian dies at 57; host of NPR’s ‘Morning Edition’ on KPCC

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.