Why evangelicals are splintering and what it means for the GOP

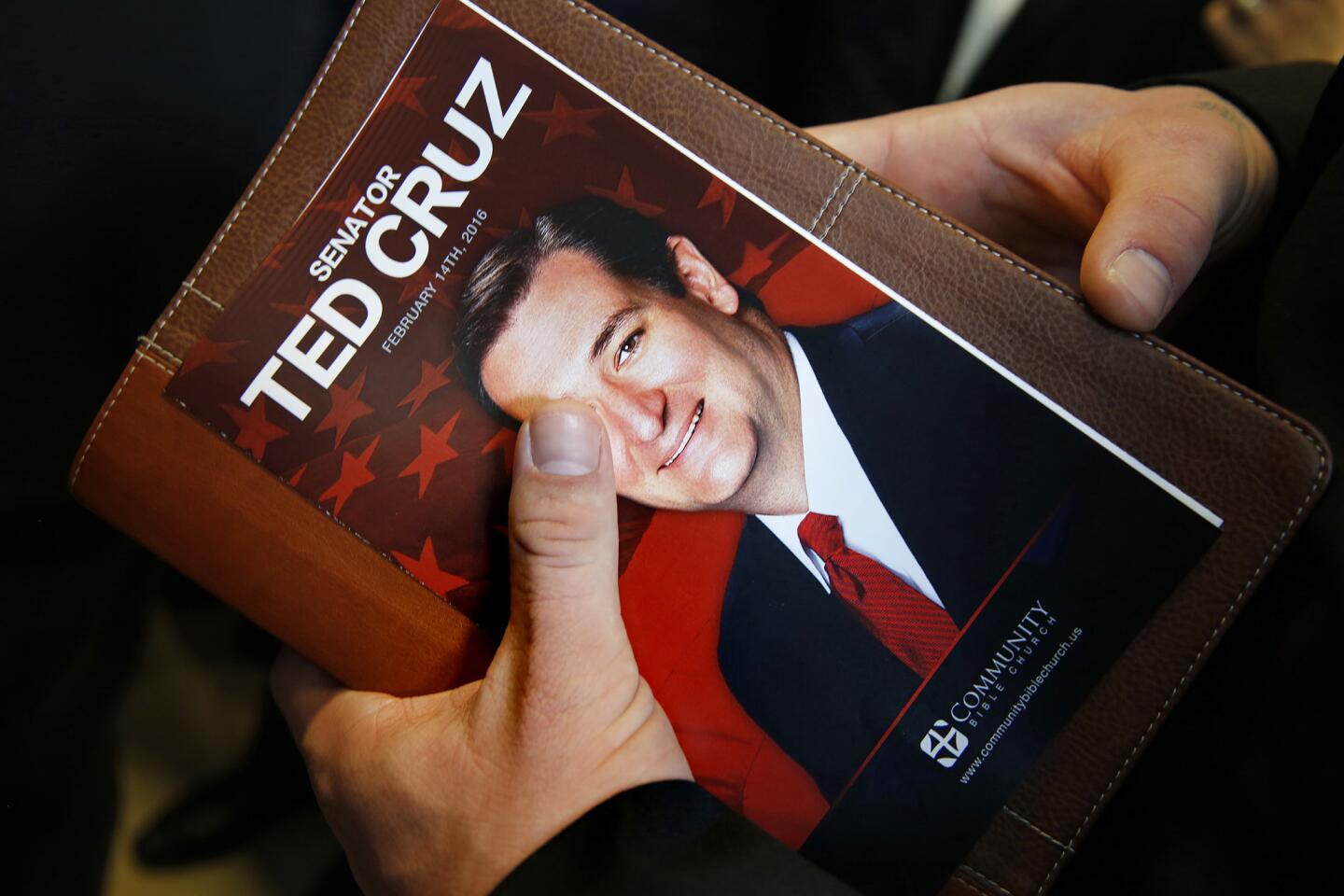

Sen. Ted Cruz shares his testimony and thoughts with the congregation at Community Bible Church in Beaufort, S.C., on Feb. 14.

Reporting from Columbia, S.C. — When Southern Baptists named Russell Moore to a top leadership post, conservative evangelicals winced.

Moore supports immigration reform, advocates improved race relations and counseled tolerance after the Supreme Court ruling on gay marriage.

To some, he is the Pope Francis of the evangelical South, and they don’t mean it as a compliment.

To others, he is a long overdue voice nudging conservative Christians away from the us-versus-them rhetoric of the past, and reshaping evangelicals’ long-standing alliance with the Republican Party.

Much like the GOP itself, the evangelical movement is going through an identity crisis.

It’s a fissure that has been widened by the 2016 presidential campaign, particularly as the race moves to South Carolina, a gateway to the Bible Belt and the next battleground primary state.

As older, predominantly white churchgoers age and a younger generation thinks differently about faith, evangelicals are fracturing as a voting bloc and the power of pastors to all but endorse candidates from the pulpit is fading.

Many churchgoers are frustrated with what they see as a long list of broken promises from GOP leaders, and by their own religious hierarchy, which helped deliver those politicians to office.

Much in the way the GOP is torn between forces seeking a more inclusive party and those pushing politics further to the right, church leaders are struggling with how best to keep evangelicals united.

“That’s the debate the Republican Party’s having and, in many ways, that’s the debate American evangelicalism is having,” Moore said, who encourages evangelicals to be more inclusive and less insular as part of their faith.

“Preaching to the choir has become an industry in American life, and that’s not how one brings change,” he said. “We want to be speaking to persuade, not just to vent our outrage.”

Division among evangelicals was starkly revealed in the Iowa caucus. Turnout was robust — 64% of GOP voters identified as evangelical – but they splintered: Ted Cruz won 37% of the evangelical vote, Donald Trump drew 22% and Marco Rubio got 21%.

Prominent evangelical leaders are similarly divided. Despite a private meeting in the summer of 2014, called specifically to unify around one presidential candidate, evangelical leaders are going their separate ways.

The most high-profile break came when Jerry Falwell Jr. praised Donald Trump on stage at the nation’s largest evangelical campus, Liberty University, even though many conservative Christians view the billionaire’s coarse language, divorces, bankruptcies and casino-generated wealth as anathema to their faith.

Other prominent leaders — Bob Vander Plaats, Tony Perkins and James Dobson — coalesced around Ted Cruz, the born-again Texas senator, who has meticulously cultivated Southern pastors one church at a time.

He continued that effort Sunday with a stop with his wife and kids at Community Bible Church in Beaufort, S.C.

“Come out and vote your values,” Cruz told the packed congregation. “Turning the country around is simple if Christians rise up as one.”

Rubio, meanwhile, is quietly consulting with a less overtly political generation of pastors, including Rick Warren in California, who has provided the Florida senator with counsel but has declined to endorse any politician.

The endorsement wars have turned sharp at times.

Moore, as president of the Southern Baptist Ethics & Religious Liberties Commission, is not endorsing a candidate. But he launched into a tweet-storm over Falwell’s embrace of Trump as a philanthropist and family man.

“This would be hilarious if it weren’t so counter to the mission of the gospel of Jesus Christ,” Moore tweeted last month as the speech unfolded on the campus founded by Falwell’s late father. “Winning at politics while losing the gospel is not a win.”

Evangelicals first emerged as a potent electoral force with the rise of the elder Falwell’s Moral Majority in 1979, credited with helping to elect Ronald Reagan. Leaders barnstormed the country calling for a return to Christian values as an alternative to the nation’s growing secularization.

The organization disbanded at the end of the Reagan era, confident it had accomplished its mission.

Today evangelicals account for about 25% of the national population, according to Pew Research Center. They continue to vote overwhelmingly for Republicans, opposing most Democratic candidates’ views on abortion, gay marriage and other topics.

But the fraying political cohesion among evangelicals is threatening to diminish their influence.

Vander Plaats, who convened the private 2014 meeting aimed at bringing church leaders together, predicted evangelicals will remain a strong force in the election.

“People of faith are going to have a voice in this process,” he said. But Vander Plaats, who has been pressing his fellow pastors to support Cruz, acknowledged the divisions. “We’re going to see if we can have a unified voice,” he said.

As the primary battle heads toward the Southern states, Moore sees evangelical voters sliding into three distinct blocs.

Trump backers include those who are willing to look past the celebrity candidate’s lifestyle because they are so fed up with Washington politics and ready for the “big change” he promises.

Religion may not be their top issue, just as women’s issues don’t lead all females to support Hillary Clinton and Latinos don’t always rank immigration as their first priority. So-called “prosperity gospel” enthusiasts are also attracted to Trump’s financial success, and are willing to overlook his stumble on the correct way to say 2 Corinthians, which drew snickers during his Liberty speech.

On Sunday, Ray Pridgen, a father of three, turned out to hear Cruz speak at the Beaufort church and was impressed by the senator. But he was still tempted by Trump’s business sense.

“As a Christian, you are called to follow your faith,” said the food services general manger. “That’s the hard toss up between the secular and the religious aspects of it.”

The older, more traditional wing of the evangelical movement sees Cruz as their best chance to lead the political class to policy solutions more in line with their Christian values. He opposes drafting women into the Army and called the Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage “lawless.”

Though Cruz has distinguished himself as an outsider on Capitol Hill and butted heads with what he terms the Washington “cartel,” he’s seen as the “establishment” favorite of old-school evangelicals.

“Everything in his background would indicate to me he is one of us,” said Pastor Bill Monroe, who has led Florence Baptist Temple in South Carolina for more than 40 years.

This group is alarmed by the growing secularization in America. In 2014, the share of the U.S. adults that identified as Protestant Christians slipped below 50% for the first time, according to Pew, while those unaffiliated with any religion rose to more than 1 in 5.

Monroe said he hoped Cruz could at least slow that trend. “Maybe just holding it back a little longer is the best hope.”

Rubio appeals to the children of the Moral Majority, who aren’t necessarily more liberal or secular than their lineage, but prefer the come-as-you-are inclusivity of today’s cargo-shorts-and-guitar-rock churches.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

These younger, more ethnically diverse Christians are just as theologically focused, Moore said, but they are skeptical of politicians who “use the gospel as mascot.” They are seeking more authentic expressions of both politics and faith – beyond the bubbles of self-selective groups who get their news largely from Fox News.

For many of them, Rubio’s attempt to tackle immigration reform and his comment that he would attend a friend’s same-sex marriage better reflects their brand of Christian values, Moore said.

Moreover, this group includes many of the nonwhite evangelicals who are now one of the fastest growing segments, and whom Republicans most need to reach.

“These evangelicals are not going to be easy for politicians to get in line,” Moore said. “These evangelicals are the future of where evangelicalism is at.”

Twitter: @lisamascaro

ALSO

Obama unlikely to alter Supreme Court ideology with Republican Senate

Hillary Clinton’s two-part strategy for derailing Bernie Sanders’ campaign

Donald Trump attacks Jeb Bush in personal terms, as death of Scalia hangs over GOP debate

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.