Poor neighborhood endures worst LAX noise but is left out of home soundproofing program

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m on Spectrum News 1.

- Share via

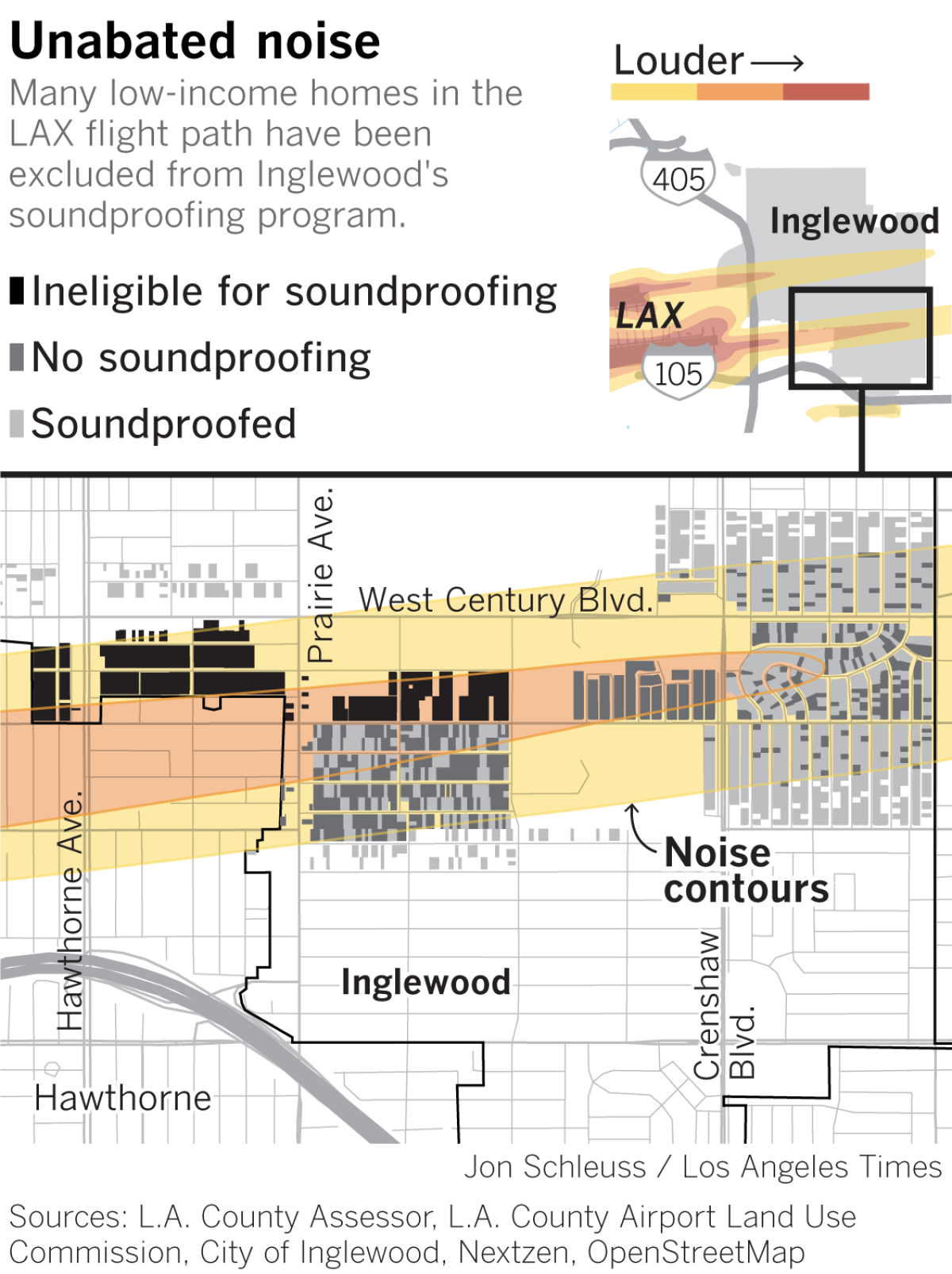

Inglewood spent millions of dollars in public funds to soundproof middle-class areas of the city while bypassing one of the poorest neighborhoods where the roar from the Los Angeles International Airport flight path is loudest, according to a Times data analysis.

Over the last several decades, the Federal Aviation Administration and Los Angeles World Airports have given the city nearly $400 million to purchase and demolish hundreds of homes around the flight path and soundproof thousands of others.

For the record:

2:35 p.m. June 8, 2019This story has been updated to add that soundproofing is underway at 55 units in the Darby/Dixon apartment village and to include additional information that was provided by the city after publication about the soundproofing program and development. The headline also was changed to clarify that it is one poor neighborhood in particular that has been left out of the soundproofing program.

A Times review of local and federal records shows Inglewood spent the money for soundproofing disproportionately in middle-class — and primarily single-family — neighborhoods on the east side of the city, farthest from the airport. Most of the eligible homes there received soundproofing.

Meanwhile, the city’s zoning rules prohibited improvements in a struggling neighborhood of about 1,200 homes and apartments along the Century Boulevard corridor.

Every two to five minutes a jetliner flies directly over Jose Peralta’s rooftop, so low that windows rattle. As the roar intensifies, conversation ceases, resuming after a few seconds to fill the moments until the next plane comes.

As warmer weather arrives, the family’s bedroom windows will remain open all night because there is no air conditioning — an amenity that came free of charge for houses that were soundproofed.

The worst time is bedtime, Peralta said. Planes fly over until midnight. Occasionally weather dictates later flights, waking the children, who think there’s a monster.

“Every day … this is how it works,” Peralta said. “We have no choice. We have to continue to live.”

The Times analysis also found hundreds of units in an apartment village called Darby/Dixon, just east of Peralta’s neighborhood, that were eligible for FAA funding but have not yet been soundproofed.

Presented with the analysis, Bettye Griffith, director of the city’s residential sound insulation program, said that property owners in that neighborhood have now been offered soundproofing and that work is underway on 55 units. She said she didn’t know why the area was left out of the federal funding program for more than two decades.

One of California’s last black enclaves threatened by Inglewood’s stadium deal »

Inglewood also used noise abatement funds to further its redevelopment strategy, purchasing and clearing properties along Century Boulevard for commercial projects. The city’s development program for those properties stalled after the economic collapse of 2007, leaving a patchwork of vacant land that is now being sought by the Clippers for a basketball arena.

Amid the current affordable-housing crisis, the city is facing pressure to offer that land for housing. In answer to a lawsuit contesting the Clippers’ plan, attorneys for Inglewood wrote that “housing directly under the flight path of one of the busiest airports in the world, as this lawsuit seeks, makes no sense.”

Many residents who spoke to The Times said they have adapted to the noise.

Ricardo Lara, a 13-year homeowner on Doty Avenue, said trash and drug dealers are the biggest problems on his street. But occasionally poor weather forces takeoffs to the east, and then his whole house shakes.

Lara said it’s “too noisy, very bad.”

A historical irony

The lack of any noise mitigation in the neighborhood most affected by noise is partly a historical irony.

Inglewood officials decided decades ago to eliminate homes on the city’s western boundary where the noise exposure was greatest and blight was encroaching. They rezoned the area south of Century Boulevard to industrial.

The change prohibited future improvements to the housing, and makes the area ineligible for FAA funding under the rules of the noise mitigation program.

The hope was that, over time, the city could encourage or carry out by itself the removal of the area’s homes using redevelopment and noise abatement funds. But there was never enough money to buy all the homes, and the rezoning prevented the city from spending federal and airport funds to soundproof those that remained.

Instead, the city focused its redevelopment efforts on removing housing in the two blocks nearest to Century Boulevard — land most suitable for stores and office space. Century Plaza, a shopping center with a Costco and other stores, stands on land purchased with noise abatement funds.

In 2003, Inglewood sought $218 million to purchase 545 properties south of Century Boulevard. The money would have cleared Peralta’s neighborhood east of Prairie Avenue as well as homes west of Prairie that are also zoned industrial.

But the money wasn’t available, and the application fizzled.

New residential development is still banned.

When investor Michael Braum picked up an abandoned medical building at 104th Street and Prairie in 2008, he hoped to convert it to residential.

“I begged the city to let me convert it to a hotel, apartments,” he said.

The answer was no.

“They have these airs of what their city needs to look like even though there is blight or abandoned buildings everywhere,” Braum said.

Wealthier areas first

Five years ago, the Inglewood City Council approved a housing plan that would “ensure all structures in the aircraft flight path have sound insulation completed.”

The flight path, as defined by the FAA, is an elliptical area where sound measurements average 65 decibels, a level at which conversation becomes difficult when planes fly over. The noise contour of the southern runway extends west and slightly north, crossing Century Boulevard at about the city boundary, where it is about 10 blocks wide. Noise is greater in the center, along 104th Street, and farther west, over Peralta’s home, where the average decibel level rises to 70.

Planes flying over homes there reach up to 90 decibels, the level at which ear protection is recommended for prolonged exposure.

In all, Inglewood has soundproofed more than 7,000 housing units and will continue work on an additional 2,400 eligible units. Some of those are in the area south of 104th Street, where about half the homes have been upgraded. City officials say properties there and in other low-income areas often do not qualify for FAA funds because they are not up to code.

In Darby/Dixon, Griffith said, about a third of the 612 units were found to have code violations and the owners of an additional 30% chose not to participate in the voluntary program.

The rules of the noise abatement program did not require Inglewood to use the funds on homes where the noise from planes is the worst. A loophole in the regulations allowed the city to soundproof properties outside the 65-decibel area if they were part of a block partially within it. In 2014, the city used the loophole to soundproof more than 800 homes beyond the boundaries of the noise contour — almost exclusively near the city’s eastern boundary.

Mayor James T. Butts Jr. declined to be interviewed. In an email, he said the city had a deadline to spend the noise abatement funds under a legal agreement with the airport and chose to soundproof the homes that were outside the 65-decibel area now and focus on others later.

Anger over the disparities surfaced on an Inglewood resident’s Facebook page last year, putting Butts on the defensive.

“You can’t tell me we don’t hear the planes just as loud,” wrote one resident who said she lived a block outside the area that is eligible for soundproofing.

“The funds cannot be used for residences outside the Flight Path,” Butts replied.

Butts was more emphatic responding to a post suggesting that political influence decided which homes received upgrades. “We cannot spend grant funds on any house outside the contours for any reason,” he posted. “We cannot.”

Affordable-housing concerns

FAA and airport funds, which mainly come from taxes paid by fliers, have also paid to sound-insulate thousands of homes in the cities of Los Angeles and El Segundo and unincorporated areas including Lennox west of Inglewood and closer to the airport’s runways.

Los Angeles County officials have taken a different direction than Inglewood, investing the funds to save homes where aircraft fly nearer to the ground and are louder.

The county has soundproofed more than 3,000 housing units there. County officials said about 1,200 more will receive soundproofing, covering 95% of the neighborhood.

Current soundproofing techniques make it possible to lower the noise level inside homes to an average of 45 decibels, about the level of quiet conversation.

In light of a housing shortage that is contributing to the region’s homeless crisis, affordable-housing advocates are demanding that Inglewood take action to protect homes in Peralta’s neighborhood and restore housing on the vacant land sought by the Clippers.

Butts says the city’s hands are tied by the agreements it reached with the FAA to obtain noise abatement funds. In a 2017 letter to the mayor, FAA Los Angeles office manager David F. Cushing cited those agreements and endorsed the city’s land reuse plan, “which limits redevelopment of acquired noise-land to commercial and industrial purposes.”

But attorneys for two Inglewood residents groups have filed lawsuits opposing the Clippers’ project. They contend that housing constructed, or retrofitted, to the 45-decibel standard would be compatible with the airport.

Douglas Carstens, who represents a group called Inglewood Residents Against Takings and Evictions, said homes next to the proposed arena pose an environmental concern that the city — or the Clippers — will have to address before closing any deal, and should have already done so.

“If their theory is they’re not going to mitigate these houses because they’re [not in a residential zone], I find that absurd,” Carstens said.

For Joan Ling, a lecturer in the UCLA Urban Planning Department and board member of Housing California and MoveLA, the idea of building new housing in the flight path doesn’t seem prudent, but she sees no justification for denying sound relief to those living in the existing homes.

“What’s important is for the city to go out there and do some ground-up planning and figure out what the community members want,” Ling said.

While the courts sort out whether a basketball arena or housing is right for the vacant land to the north, residents of 103rd Street expressed little stake in the outcome.

“I’m kind of used to it,” said Francisco Guerra, chatting with a friend outside his apartment one Sunday. “I went to another area; it makes me feel kind of like, ‘Where’s the noise at?’ When I’m back here I feel like home.”

On the other hand, he said he wouldn’t turn down soundproofing.

“That would be nice to change the windows,” he said. “I understand peace and quiet is good for you.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.