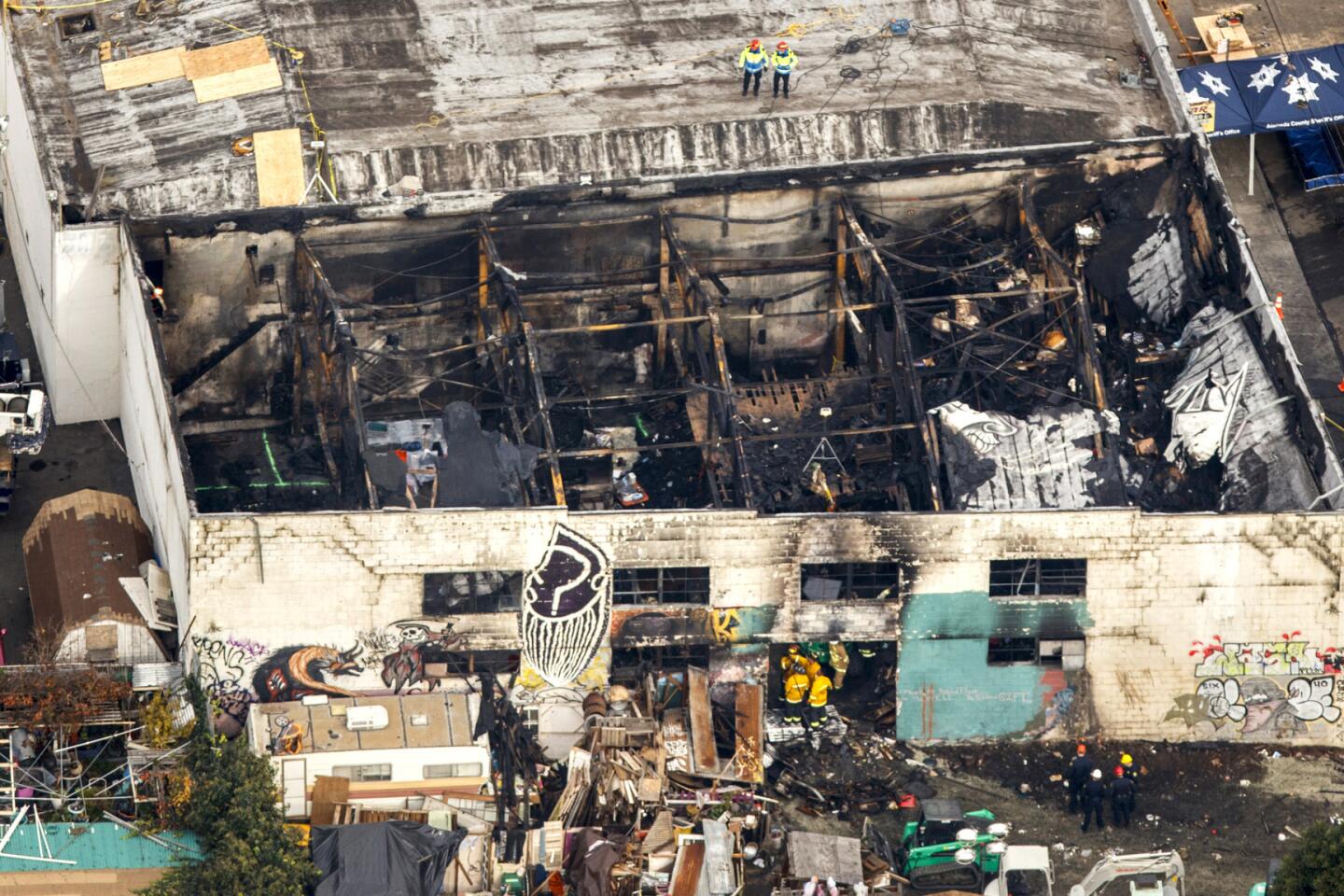

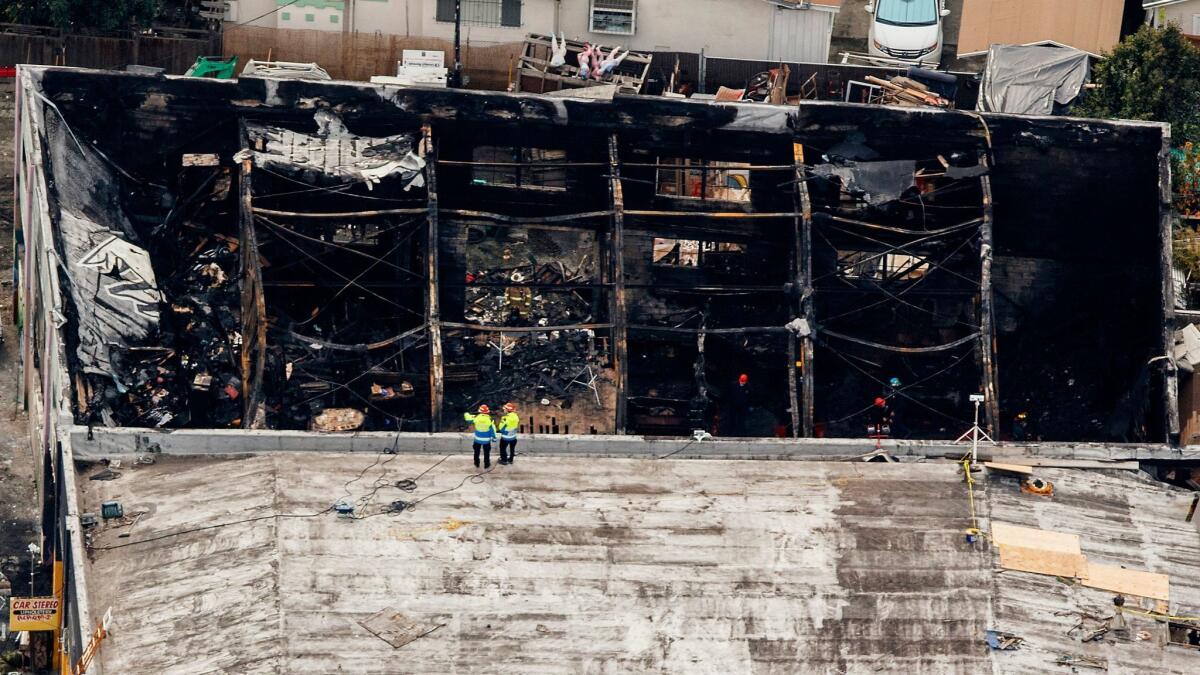

Amid Ghost Ship’s enchanting disorder lurked danger and the seeds of disaster

Reporting from Oakland — They were drinking at Aunt Charlie’s Lounge, an old gay bar in the Tenderloin known for its drag shows and cheap steaks.

It was Friday evening in San Francisco, and Jay Marsh, 31, and his friends planned to hit a few parties across the bay, in the Fruitvale district of Oakland.

For the record:

11:27 p.m. Jan. 8, 2025This article states that the children of Ghost Ship manager Derick Ion Almena and his wife, Micah Allison, were not allowed to live in the facility after having been removed by county children’s services officials, according to Danielle Boudreaux, a friend of Allison’s. Boudreaux said the children were prohibited from being at the warehouse while events were being held there.

“Nackt is playing in that warehouse on 31st by the Wendy’s,” a friend said.

A little tide of nerves washed through Marsh. He knew he had to go back to the warehouse he once lived in. He couldn’t be scared anymore.

::

Two years ago in August, Marsh had finally found his own pad in the Bay Area for $300 a month.

At the back of a warehouse in Oakland, above an old RV, Marsh hoisted his bed up a 12-foot ladder to a piece of plywood atop four wooden stilts.

It was more fort than loft — for walls, he hung Moroccan fabric from the building’s ceiling joists.

The manager and his longtime partner stopped by. Two days before, he had met them and their three children, and came away liking their sense of artistic whimsy and charm.

::

But on move-in day they were agitated and rambling half-coherently, barking at their kids, losing their trains of thought. Marsh said the manager, Derick Ion Almena, then 45, was obsessed with showing him a piece of metal he had found on the roof.

Marsh was a bit unnerved, but shrugged it off. Only later would he question why he didn’t walk away that day.

He climbed up to his perch and took in the surrounding of trailers and stilt houses, a burgeoning art colony.

Jay Marsh lived at the Ghost Ship for a few months in 2014 but left after becoming increasingly uncomfortable. He had planned to return to the warehouse for the first time on the night of the ill-fated party.

Two trailers flanked him, with their own lofted platforms above. Pallets connected some of the elevated spaces, creating a floating floor that snaked throughout the building.

On the ground directly below him, Almena had piled scrap lumber for people to build with. In front of him, a barricade of wood — old pianos, organs, cabinets, a 1950s box television, salvaged shutters, Balinese chests — divided the space. A communal “living room” sat behind it, where the manager held acoustic concerts. Ganglia of extension cords splayed out, powering microwaves, refrigerators, space heaters, laptops and old lamps.

There was something Old World and fantastical about the setup, a child’s dream, like a village of treehouses with no adults to say no: Hang mannequins from the ceiling if you like. Hammer antlers to a post. Play music until dawn. Run barefoot among the splintery boards and rusty nails.

And Marsh, who is transgender, said he felt comforted that it was a “safe space for queers.”

::

Nikki Kelber moved into a space in the front around the same time as Marsh. She had been trying to find an affordable space in San Francisco, but rents were exorbitant.

At 42, she didn’t expect to be living such a communal experience, but instantly took to it. She made jewelry and loved being surrounded by other artists in what she saw as a “living, breathing art installation.”

She and her cat, Mookie, slept above the studio where she worked.

Whenever she was stumped or wanted to try a new style and needed a critique, she could just “walk over and talk to Max, talk to Anthony.”

At any time, someone was sewing, painting or making music. With dozens of pianos and organs scattered about, notes and chords chattered and chanted back and forth through the air.

On her birthday, her housemates would surprise her with cake and dinner. They’d share meals together every day at a big table. They came together in impromptu jam sessions. People who couldn’t play an instrument suddenly became musicians.

They even built a recording studio.

Almena advertised the building on Craigslist as a “hybrid museum, sunken pirate ship, shingled funhouse, and guerrilla gallery.”

To Kelber, it was enchanting.

::

Marsh felt the same at first, even when the electronic dance parties on the rooftop above thumped the ceiling just over his head. He had been a coffee broker in New York, regularly traveling to Brazil, but had moved back to the Bay Area after a friend died. He lived off savings and did creative writing.

Then, about a month into his stay, he was hanging out with a few people in the trailer next door.

He said Almena’s girlfriend, Micah Allison, was smoking a cigarette and yelling at her younger children, ages 5 and 3, to stay close by, but not come in.

Marsh had been growing more concerned about his safety. The atmosphere was erratic, with random people coming through at all hours. Almena, who took on the air of a guru, would fly into rages.

Marsh worried about the couple’s children, wandering with little oversight. He had driven them to Goodwill to buy them shoes, just so they didn’t step on a nail.

Allison stepped out of the trailer and flicked her cigarette butt. Marsh watched it burn out next to the woodpile beneath her platform. The boards were old, dry and brittle, more like studs you’d rip out of a century-old bungalow than you’d buy from Home Depot.

Suddenly the fantastical terrarium had a menacing cast. It could be an inferno within seconds.

Marsh drove to an Army-surplus store and bought a knife, a canister of Mace and a fire extinguisher. He slept with all three at his side, and started scanning Craigslist for new places to live.

He was happy to baby-sit a friend’s Lab-pit bull mix named Shallah. The dog could scamper up the wood ladder to his loft, and helped him feel more secure.

One night in November 2014, when Marsh had lived there just a few months, someone closed the door and Shallah could not get outside, and she relieved herself on the warehouse floor.

Marsh said Almena stormed up to him in a rage that seemed far overblown for the situation. Marsh said Almena screamed: “I will … kill you. I know people.” He punched a mirror with his ropy arm and his hand started bleeding. (Almena did not respond to requests for comment.)

Marsh, a good half-foot shorter than Almena, was shaking. After Almena left, Marsh threw his backpack of clothes into his car and drove away. He left his other belongings, fearful of how Almena might react to his moving out abruptly.

::

Others who came into Almena’s circle had similar run-ins.

Danielle Boudreaux had been close friends with Allison for six years by then and was deeply entwined in their lives. She had changed her son’s school to the one Allison’s daughter attended. Boudreaux’s daughter was a nanny to their younger ones.

When Boudreaux moved into the warehouse around 2013, she embraced the lifestyle. But she began to have concerns about the children’s safety there. Numerous residents openly used drugs, the space was clearly a firetrap, and strangers came and went.

“The building was full of … driftwood and nails sticking out everywhere,” she recalled. She said the front staircase was jury-rigged with pallets: “There was no code. When you stepped on it, the whole thing jiggled all over the place.”

On New Year’s Eve 2014, Almena rented out parts of the warehouse for a Museum of the Erotic sex party, which the children saw, Boudreaux said.

She called Allison’s parents to tell them the warehouse was a dangerous environment for their grandkids. She said the family complained to the county’s children and family services agency, which removed the three kids in March of last year.

Almena posted on Facebook about the seizure of his kids and his need to pass drug tests and take parenting and violence classes in order to get them back.

The parents regained custody of their children this summer, but, Boudreaux said, they were not allowed to live in the warehouse known as the Ghost Ship. This is why they were not there the night of Dec. 2, while so many with no connection to the place poured in.

::

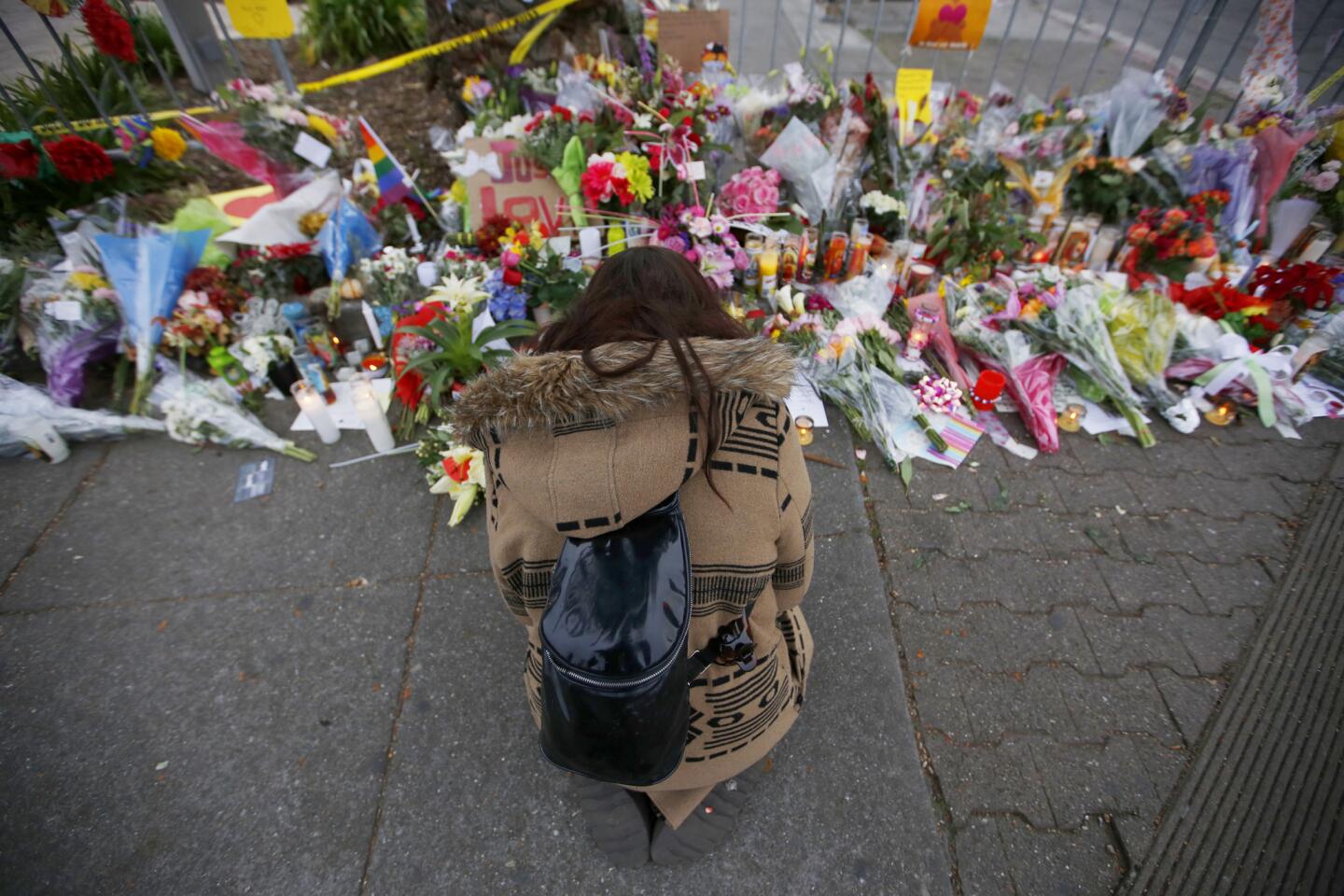

Flowers are left near an Oakland warehouse where a fire broke out during a concert, killing 36 people.

From Paris, Grace Lovio spoke to her boyfriend in Oakland on the phone before she went to bed that Friday night. She was studying abroad as a graduate student.

Jason McCarty told her that his boss at his new job “was giving him a lot of props,” telling him he’d been doing good work. It was morning in California. He said he planned to grab coffee and edit a final paper she wrote about the Salvadoran civil war.

He didn’t mention his plans for the night.

Marsh kept drinking tequila sodas with his friends at Aunt Charlie’s Lounge. He had gotten a job marketing for an app company and the holiday season was intense, with relentless deadlines. He liked to purge that pressure valve on Friday nights.

They moved to a friend’s apartment, “pre-gaming” with more drinks while coordinating which parties in Oakland they would hit.

A friend in Oakland texted that Almena wasn’t at the Ghost Ship.

Marsh had not been to the warehouse since he left, but he thought about it often. Almena still instilled fear in him, which bothered him.

The bash was being thrown by a popular Los Angeles-based music label called 100% Silk. Golden Donna, a stage name for Wisconsin-based producer Joel Shanahan, was scheduled to perform with labelmates Cherushii, Nackt and others.

Marsh didn’t care who was playing. He had been going to warehouse parties since he was 16. For him, they were refuges from the mainstream world. He loved the dancing and art and friendly faces.

They’d have a few more drinks — whiskeys and orange juice now — and they’d catch an Uber to Oakland.

::

Kelber was asleep in her studio.

She awoke to her friend Carmen saying something about smoke and fire.

She grabbed a fire extinguisher and looked down the hallway and saw 15-foot flames raging in a twisted ball.

Realizing the extinguisher would be futile against it, she tossed it and grabbed her cat carrier from the loft. A wall of black smoke hit her, making it almost impossible to see or breathe. The power went out. Voices were screaming. The pressure differential pushed her window open, and the draft gave her some air but fanned the flames.

She managed to grab a headlamp, and scramble for the exit with her cat.

Within seconds, she was outside, watching 20-foot flames roar out of her very window.

::

When Lovio woke up Saturday morning in Paris, the edits from her boyfriend were in her inbox, along with messages he’d sent her on Facebook.

“Love you a zilliopzazillion,” he wrote.

He’d also forwarded her tickets to a standup comedy show he’d purchased for her 24th birthday, coming up Dec. 18.

She had to study for her last final exam. In the afternoon, she took a break and logged into Facebook.

A friend had posted an article about a fire that ripped through an electronic music concert at an Oakland warehouse the night before, claiming the lives of at least nine people. Authorities said as many as 40 bodies may be inside.

Dread bubbled up. That was the kind of event her boyfriend would have liked.

She shot him a quick message, asking if he was OK.

“Type anything,” she wrote, like so many others frantically trying to reach their loved ones.

He didn’t respond, which was unlike him. She continued scrolling through news stories, some of which displayed photographs of those who were unaccounted for. In one article, she came across her boyfriend’s photograph.

She could barely breathe.

On his Facebook page, his friends posted messages looking for him, asking if he was all right. She dialed his number, and called him via FaceTime, several times. No answer.

He always told her, “If you need me, I’m one ring away.” He had been true to that, always picking up on the first call.

Within a half-hour, she’d booked a flight from Paris to San Francisco, with a stop in Dublin, and flew out the following morning, skipping her last exam.

During the agonizing journey, she carried with her a diary filled with the poetry McCarty, 36, had written for her since they met in October 2015. He loved to speak in poetry, and she found it endearing.

When she landed in San Francisco on Sunday afternoon, Lovio still couldn’t find him, and authorities had not identified most of the 33 bodies they had recovered by then. She drove to her father’s home in Concord, not knowing, while her boyfriend’s body lay in the rubble.

McCarty was one of 36 people who died that night, most of them at the party. Kelber would know of only one resident who perished.

Authorities would say they believed the fire was electrical, but have not determined the exact cause.

::

Marsh woke up Saturday morning with a hangover and texts about a fire.

The night before, more people kept arriving at the pre-party at the apartment. They kept drinking. His friend Max kept rallying them to head out, but ultimately they lost their energy to go to Oakland.

It was the first time in months he hadn’t stayed out late on a Friday night.

Now he stared at the video on his phone in horror.

It felt eerie that he had not been there, like the passenger who missed the flight that crashes.

All the images rushed back. The woodpile, the wires, the drugs.

And he grieved for all those people, like him, who went there looking for a safe space.

St. John and Karlamangla reported from Oakland, Mozingo from Los Angeles.

Times staff writers Jack Dolan, Alene Tchekmedyian and Anna Phillips contributed to this report.

ALSO

‘We’re all hurting’: Mourners gather at Oakland museum to remember victims of Ghost Ship fire

Refrigerator ruled out as cause of Oakland fire that killed 36; no evidence of arson

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.