California should help pay for earthquake early warnings, state lawmakers say

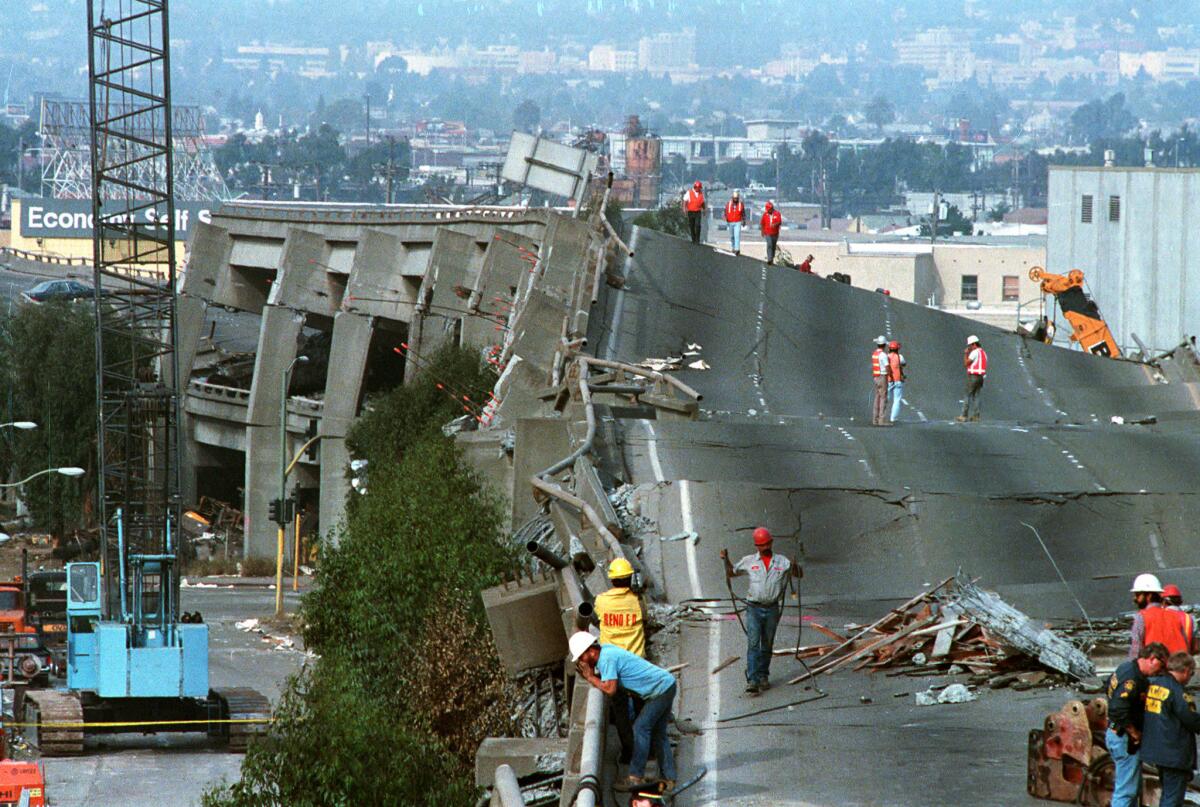

The magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989 did massive damage in the San Francisco Bay Area, including to Interstate 880 in Oakland.

Hours after a magnitude 6.4 earthquake destroyed buildings and took lives in Taiwan, four state lawmakers said they want California to help fund an earthquake early warning system that has been stalled by a lack of money.

“There’s no valid reason not to make this relatively small investment in an early warning system that has the potential to save the lives of Californians,” state Sen. Jerry Hill (D-San Mateo) said in a statement. “I urge my colleagues and the governor to join us in fulfilling our primary responsibility of protecting the public.”

Added state Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys), a former speaker of the state Assembly, in the statement: “It’s crucial that we fund a statewide earthquake early warning system and get it in place right away.”

The voices of support that emerged for the warning system Friday mark a change in tone at the state Capitol, where outspoken backers of the system have been few in recent years. On Tuesday, H.D. Palmer, deputy director for the Department of Finance, said that California’s policy is to not use money from the general fund for the early warning system.

But it was becoming increasingly unclear when the public could expect to see the earthquake early warning system on their cellphones, computers and televisions, with no solution in sight for full funding.

The total cost of building the system across the West Coast has been esimated at $38 million, plus $16 million a year to operate it. For California alone, the cost is $23 million to construct the network, and $12 million annually thereafter.

Congress and President Obama have already kicked in about half of the $16-million annual cost to operate the program, but federal elected officials have said California, Oregon and Washington should also help pay for the network.

Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank) hailed the interest of state lawmakers in the system Friday.

“I’m thrilled .... I’m really encouraged by what’s happening,” Schiff said in a telephone interview Friday. “It was all the more apparent this week that we need the full buy-in by the state of California, and now we have some very influential lawmakers who are making earthquake preparedness and the early warning system one of their real priorities. I think we’re really gaining traction now, and it’s great news for California.”

Schiff said he would work with state legislators to build support for the proposals, which he said were critical to completing a full earthquake early warning system. “While the federal investment has been critical to our getting to this point, the federal government cannot, and will not, fund this system on its own,” he said.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s earthquake early warning system was highlighted Tuesday at a summit held by the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy. The summit gave high-profile backing to the early warning system, and speakers urged policymakers to find a way for the system to be completed.

The prototype early warning system has already shown promising results in its test phase — 30 seconds of warning reached downtown Los Angeles before the ground shook from a magnitude-4.4 earthquake centered in Banning some 80 miles away last month. In 2014, researchers in San Francisco reported the system gave eight seconds of notice before the shaking arrived from a magnitude-6.0 earthquake that began in Napa.

But the system doesn’t have enough seismic sensor stations to adequately cover the state and West Coast. A thousand more need to be built or upgraded, adding to the existing network of 650 facilities, which have been largely focused on the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas.

The blind spots are important to fill. A lack of sensors in the northern reaches of California means that San Francisco could receive delayed warnings if an earthquake occurred near Cape Mendocino and its shockwaves barreled south to the Bay Area.

Other countries have developed earthquake early warning systems after devastating quakes killed thousands of people. Mexico City has had a system since 1991, built after a 1985 earthquake killed at least 9,500 people.

Japan built a nationwide early warning system after the 1995 Kobe earthquake killed more than 5,000 people. When the magnitude 9 earthquake hit east of Japan in 2011, many people in Tokyo, 200 miles from the epicenter, had 30 seconds of warning that the shaking was coming.

The warnings would cause elevators to automatically open at the next floor, give surgeon time to halt surgery, and slow down trains to decrease the risk of derailments. In Japan, one factory has figured out a way to secure noxious chemicals between the time a quake warning is issued and when the actual shaking arrives.

The early warning system works on a simple principle: The shaking from an earthquake travels at about the speed of sound through rock — slower than the speed of today’s telecommunications systems. That means it would take more than a minute for, say, a 7.8 earthquake that starts at the Salton Sea to shake up Los Angeles, 150 miles away.

The two senators, Hill and Hertzberg, and Assemblyman Adam Gray (D-Merced) said they wanted to repeal a current state law that prohibits the spending of state general fund dollars on an earthquake early warning system. They’re also proposing $23 million to install earthquake sensor stations and upgrade telecommunications networks to get the system up and running in the state. The proposal, however, does not address ongoing operational costs.

“We will have conversations with project stakeholders about how to maintain the system’s operability and long-term financing,” Hill and Gray said in a statement.

They added that the state legislative analyst recently predicted that California will end the next budget year with a reserve of $11.5 billion.

“We should use a small fraction of that money to make a smart, one-time investment in a system that can improve public safety and save lives,” the lawmakers said. “We share Gov. [Jerry] Brown’s commitment to fiscal restraint. However, to not invest a small fraction of the overall state budget to implement the earthquake early warning system would be fiscally irresponsible.”

Assemblyman Adrin Nazarian (D-Sherman Oaks) said he wanted to secure funding to both build the early warning system and operate it through the budget process.

During budget negotiations, Nazarian also plans to re-introduce the idea that the state should give building owners a tax credit for earthquake retrofits; for instance, for every $100 spent on a qualified retrofit, a building owner would receive a $30 break on income or corporate taxes over a period of five years after the retrofit is completed.

Nazarian introduced the idea as a bill in the last legislative session; it passed the Legislature and was vetoed by Brown.

“Every second matters in an earthquake,” Nazarian said in a statement. “Let’s get this done.”

[email protected] | [email protected]

Follow us for the latest news in earthquake safety, El Nino, and the drought: @RosannaXia and @ronlin

ALSO

Open-air urinals in S.F. park ‘disgusting,’ critics say

Doctor convicted of murder for patients’ overdoses gets 30 years to life in prison

Taiwan earthquake topples buildings, leaving at least 13 dead and hundreds injured

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.