Bullet train’s first segment, reserved for Southland, could open in Bay Area instead

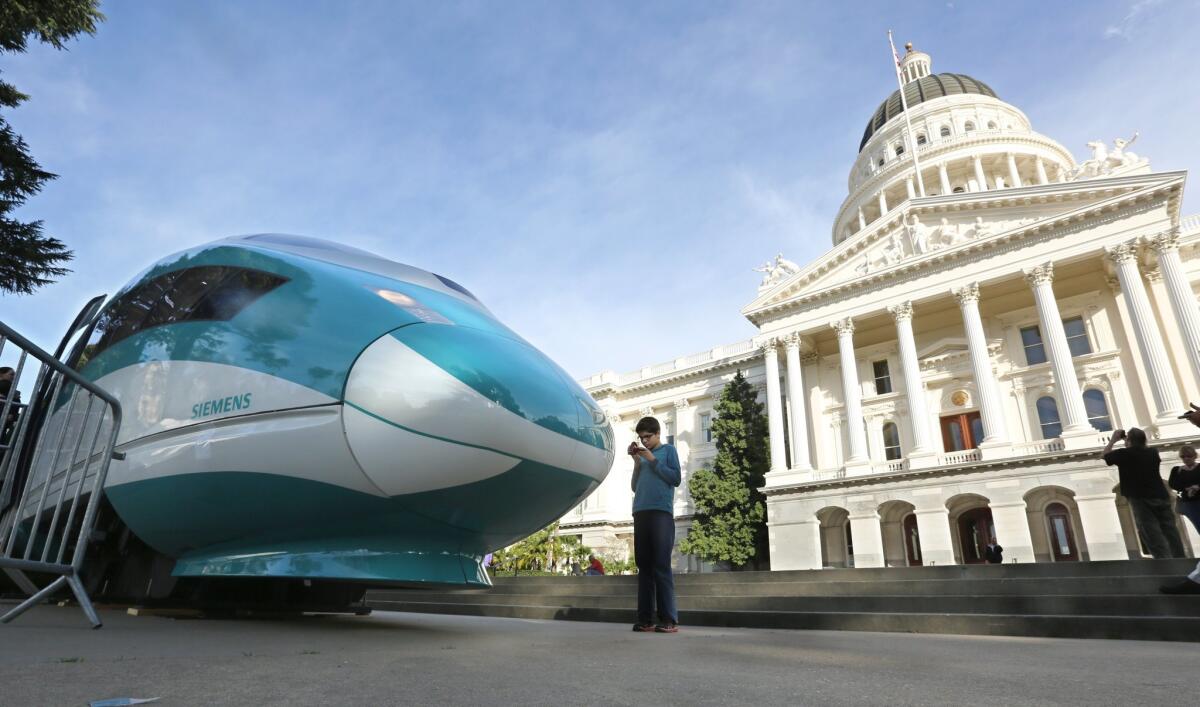

A full-scale mock-up of a high-speed train was set up outside the Capitol in Sacramento on Feb. 26, 2015.

A valuable perk handed to Southern California from the bullet train project — a 2012 decision to build the first operating segment from Burbank north into the Central Valley — is being reconsidered by state officials.

The state rail authority is studying an alternative to build the first segment in the Bay Area, running trains from San Jose to Bakersfield.

If the plan does change, it would be a significant reversal that carries big financial, technical and political impacts, especially in Southern California.

“You can’t ignore Southern California or Los Angeles or Orange County and say we are going to go north, period,” said Richard Katz, a longtime Southern California transportation official and former Assembly majority leader. “It made sense to start in the south, given the population and the serious transportation problems here.”

The original decision to start the initial segment in Burbank was considered a major economic benefit to the region, providing commuters with 15-minute rides to Palmdale, a connection to a future Las Vegas bullet train and an early link to the growing Central Valley.

But the state is facing major difficulties with the south-first plan. By building in the north initially, the state would delay the most difficult and expensive segment of the entire $68-billion project: traversing the geologically complex Tehachapi and San Gabriel mountains with a large system of tunnels and aerial structures.

With the project already behind schedule and facing estimates of higher costs, the Bay Area option could offer a faster, less risky and cheaper option. Getting even a portion of the project built early would help its political survival.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

The outcome of the new evaluation will be known in the coming weeks, when the state unveils its 2016 Business Plan. The document will be the most comprehensive update for the $68-billion program in four years.

A decision to drop its plan to start the system in Southern California will not be popular among area civic leaders.

“I understand they have a difficult political situation, but they really need to come to Los Angeles,” said Art Leahy, chief executive of the Metrolink commuter rail system in Southern California.

“The southern route has a lot more ridership,” Leahy said. “The north is very important and I love the Bay Area, but the economic center of the state is in Southern California.”

We have long warned that the authority is not being honest with the public about the true costs of constructing high speed rail in California.

— Rep. Jeff Denham (R-Turlock)

The rail authority has been hinting at a potential change for months, starting last summer when it asked potential private investors to describe how they would help build an initial operating system from either the south or the north.

And in December, rail authority Chief Executive Jeff Morales said in a Sacramento television news interview that the agency was reconsidering its south-first strategy.

Rail authority spokeswoman Lisa Marie Alley said the plan to build an initial operating segment in the south was never final.

“The option to do an initial operating segment north has always been there,” she said.

Gov. Jerry Brown did not leave room for that possibility in 2013. In his State of the State address that year, he said the first phase of the future bullet train would start in the Central Valley and connect to Union Station in Los Angeles.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

“The first phase will get us from Madera to Bakersfield,” Brown said. “Then we will take it through the Tehachapi Mountains to Palmdale, constructing 30 miles of tunnels and bridges.

“The first rail line through those mountains was built in 1874, and its top speed over the crest is still 24 miles an hour,” Brown said. “Then we will build another 33 miles of tunnels and bridges before we get the train to its destination at Union Station in the heart of Los Angeles.”

The governor’s latest State of the State speech, delivered Thursday, did not mention the bullet train. It had been included in each of his annual speeches since 2012.

The project has fallen two years behind schedule and faced a wide range of legal, political and technical challenges. A poll last week by Stanford University’s Hoover Institution found that 53% of voters wanted the change to reallocate funding from the bullet train project to water projects.

Among supporters, the bullet train is considered an important part of the state’s future transportation system. The existing Amtrak service from Los Angeles to the Bay Area requires travelers to board buses at Union Station for a trip over the 5 Freeway Grapevine to Bakersfield, where they transfer to trains that use the Burlington Northern Santa Fe freight tracks.

A bullet train would fill that gap and could connect Los Angeles to San Francisco in two hours and 40 minutes.

If the state does switch gears, it would come after a significant amount of work to accelerate the project in Southern California. Only last week, the rail authority signed an agreement with Burbank to provide $800,000 to explore a site for a future station.

Last year, rail authority officials had encouraged Burbank not to sell an airport parcel that might be used for the system. The rail authority in September said it was in discussion with a Chinese-based company to link its bullet trains to new high-speed trains to Las Vegas.

Delaying the southern section will not make the full project any cheaper, with the difficult crossing of the mountains north of Los Angeles becoming more expensive as that segment is delayed.

“The earlier you do it, the less the costs will grow,” said Mark Watts, interim director of Transportation California in Sacramento.

A 2013 cost estimate by the state’s leading management contractor, Parsons Brinckerhoff, projected that the initial operating segment from Merced to the San Fernando Valley would cost a staggering $40 billion, about $9 billion more than had been estimated.

The higher projected cost left the state with an even bigger shortfall in funding to build an initial segment. The state will have no more than roughly $15 billion in hand by 2022, when train service is supposed to start.

The initial operating segment is the cornerstone of the entire plan, allowing an early segment to attract private investors who would help finance the complete system.

“You have a much better chance of getting the north end built,” said Paul Dyson, president of the Passenger Rail Assn. of California. “I am from Southern California, but if it’s a difference between seeing a project get built or seeing it die, it would be better to start from the north.

“If you try to build it from the south, it could delay it by a couple of decades,” Dyson said. State rail officials have said the entire system will be completed by 2028.

Dyson said the state was “way too ambitious” in attempting to build a unified statewide system in a single program.

“We bit off more than we could chew,” he said.

Twitter: @rvartabedian

MORE ON CALIFORNIA’S BULLET TRAIN

Costs rise for moving utility lines in construction of bullet train

Bids for bullet train construction show apparent winner for next phase

What’s behind a bid to shift dollars from the bullet train to water projects

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.