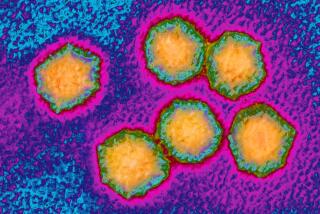

Two years after it started, San Diego declares end to deadly hepatitis A outbreak

Two years in, San Diego’s hepatitis A outbreak is finally over.

Dr. Wilma Wooten, the county’s public health officer, said Monday that enough time has now passed to formally declare a curtain call for the contagion that killed 20, sickened nearly 600 and spurred a complete rethink of how the region handles homelessness.

“Last Thursday, it was officially 100 days since the most recent case, and, for hepatitis A, that’s the threshold we use that allows us to say it no longer meets the definition of an outbreak,” Wooten said.

Detected by the health department in late February 2017, infectious disease sleuths tracked the first likely case to the week of Nov. 22, 2016. By late spring of last year, there were hundreds of cases, a dozen deaths and a growing public outcry that something had to be done about the unsanitary living conditions among the region’s homeless population.

Under significant pressure from many who work with the homeless day in and day out, the city and county government came together in September to promote vaccination and sanitation, launching street-washing campaigns, installing portable toilets and hand-washing stations and, eventually, putting up temporary shelters large enough to house 700 people at a time.

With a cost estimated to exceed $12 million, fighting the outbreak didn’t come cheap, but that expense was what it took to address years of deferred maintenance for the homelessness problem, noted Bob McElroy, chief executive of Alpha Project.

Today, Alpha Project is one of several organizations operating new shelters and McElroy says he is convinced hepatitis A was the sad proof that homelessness can’t be ignored forever.

“The reality is, if you’ve got a place for people to be safe and have access to healthcare, you’re just not going to have the kinds of sanitation issues you have with tent cities lining the streets,” McElroy said.

Though San Diego’s outbreak was significantly wound down by the first of the year — there have been only 15 new cases in 2018 — other communities across the nation are still fighting.

An outbreak map maintained by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention links to the latest outbreak updates in a dozen states, with Kentucky’s latest post showing 2,275 cases and 14 deaths; West Virginia lists 1,671 cases as of Oct. 26, and Michigan, whose outbreak began in August 2016, is now up to 898 cases and 28 deaths.

Nationwide, the combined case totals have now surpassed 8,000 with 76 deaths and more than 4,500 hospitalizations. On Thursday, the CDC is set to release a comprehensive report for all outbreaks in 2017 that should shed additional light on the situation.

Though it was far from the only place in the nation to struggle with hepatitis A spreading among homeless and drug users through fecal contamination, San Diego’s outbreak did get national attention very quickly once news broke that people were dying and case totals were growing every week.

Though Michigan’s outbreak had been running longer, San Diego’s conflagration of cases became immediate national news.

Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, speculated that the national attention attached readily to the contrast of an affluent city besieged.

“You think of San Diego as a vacation destination and now, suddenly, you’re hearing about hepatitis and unsanitary conditions,” Osterholm said. “That contrast is going to get more media attention, sort of like a measles outbreak at Disneyland is going to get more attention than one at a school in a metropolitan area, even if they have the same number of cases.”

He applauded San Diego’s willingness to spend the money necessary to get its outbreak under control, as did Dr. Jonathan Fielding, distinguished professor of the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

“Hepatitis A is very contagious,” Fielding said. Getting something like this under control, it takes money, it takes an enlightened bureaucracy and it takes a heck of a lot of coordination. It’s clear that you have that in San Diego.”

Now comes the really hard part: Sustaining what has taken so much hard work to build.

“What it shows is that this is not something you can just assume you’re going to deal with by vaccination alone. It takes looking at the sanitary conditions, the opportunities for housing and it takes listening to the people who really live in that environment,” Fielding said. “My hope is that the elected officials in San Diego, and in many places, won’t forget that. The need for resources and cleanliness does not end just because the hepatitis A outbreak is over.”

Osterholm agreed, adding that infectious disease outbreaks, in this mobile day and age, are always right around the corner.

“You can expect that you are going to see continued migrations of indigent populations to the San Diego area from other places that we know have ongoing outbreaks. So, it’s hard to say that anything is truly over forever,” Osterholm said.

There are definitely new practices in place that have continued and will continue even with the outbreak now officially over.

For example, the county first started using mobile vaccination “foot teams” to send public health nurses accompanied by law enforcement officials into homeless encampments during the outbreak. Though they’re no longer nearly so prevalent as they were, Wooten said foot teams are now a standard tool in her toolbox ready for use on a case-by-case basis.

And the county, which administered more than 200,000 vaccine doses during the outbreak, has learned a thing or two about how to do this work in collaboration with public health clinics and others.

One key lesson, Wooten said, was that it often took months to convince many of the most at-risk homeless residents to roll up their sleeves.

“When we first started going out in late April and May, people said they thought it was a government conspiracy,” Wooten said. “But we knew it would take time for this population to trust us, and we had to just keep going back and engaging in order to build that trust.”

San Diego’s public health department has also pushed for homelessness to be considered a valid indication for routine hepatitis A vaccination.

Last week, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices formally added homelessness to the official list of reasons why doctors should urge their patients to get vaccinated, concluding that living on the street doubles or triples a person’s odds of contracting the kidney-wasting disease.

Data from San Diego’s outbreak were used as a sort of case study by the panel of vaccination experts who made the decision.

Dr. Eric McDonald, medical director of the county health department’s Epidemiology and Immunization Services Branch, said it’s satisfying to see San Diego experiences help change national policy.

“It’s really good that we could use the experience here to help others, and it has been interesting to see it through to its national conclusion,” McDonald said.

Sisson writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.