The futile fight to save Autumn, a 1-year-old victim of gang violence in Compton

The father cradled his 1-year-old daughter in his arms, screaming: “My baby’s been shot! My baby’s been shot!”

The little girl had a grievous head wound. She was ominously still, not moving or crying.

The sheriff’s deputies didn’t know how far behind the paramedics were. They decided to take her to the hospital themselves.

The father got in the back seat of the patrol car with his baby.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“We’re gonna get you there. We’re gonna get you there,” Deputy Ricardo Eguia repeated during the high-speed ride as the father sobbed.

On a night shift patrolling Compton, just about anything can happen. In six years on the city’s streets as a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy, Eguia has seen blood on the sidewalk and heard the anguished wails of family members all too many times.

But even here, gang violence reaching into a baby’s crib is not routine. The deaths of children stick with Eguia, from the toddler killed by a falling television to the baby girl named Autumn Johnson who lay motionless during the frantic journey to the hospital last Tuesday.

Deputy Ricardo Eguia, foreground, and Deputy Richard Raygoza sit in their car at the Compton Sheriff’s Station on Feb. 13.

Autumn had recently celebrated her first birthday with cake and Minnie Mouse balloons. She was sleeping in her crib when a man stepped out of a blue Chevrolet Impala and began shooting at the converted garage where she lived. A single bullet struck her in the head.

Her father, 24-year-old Darrell Johnson, was an admitted gang member and may have been the intended target, according to investigators.

Homicide Capt. Steve Katz said Wednesday that the investigation was moving forward but he could release no new information. Authorities are offering a $75,000 reward for information leading to the identification, capture and conviction of the shooter.

“You start contemplating a lot of things because the child had nothing to do with anything,” Eguia said. “They’re sleeping in the crib, and now they’re not. Sometimes you don’t know what to make of it. Is it fair? Is it not fair? You don’t understand why those things happen.”

See the most-read stories this hour >>

******

The deputy’s shift began quietly: a domestic violence incident, a purse snatching.

Eguia, a training officer, was teaching the ropes to Deputy Richard Raygoza, who was five months into his first patrol assignment after seven years of working the county jails.

About 7 p.m., a call came over the radio: gunshot victim. Then, more details: A baby had been shot in the head. Raygoza hit the accelerator, hoping the dispatcher was mistaken, as adrenaline coursed through him.

When the deputies got to Holly Avenue and San Marcus Street, they found the father holding the injured baby and screaming hysterically.

They couldn’t waste a second getting the baby to the hospital, they decided. Three or four patrol cars formed a convoy behind Eguia and Raygoza, and deputies blocked off roads near St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood, about four miles away.

Evidence markers sit on the street where shots were fired into a garage on Holly Avenue in Compton, killing 1-year-old Autumn Johnson as she lay in her crib.

Raygoza was at the wheel, taking the straightaways at 40 to 50 mph while briefly slowing at intersections, while Eguia scanned the road for obstacles. The hair-raising drive took about two or three minutes.

“You’re just trying to get to the hospital as quickly as possible and safely as well,” Raygoza said.

Meanwhile, they reassured the desperate father: “We’re gonna get you there. ... We’re almost there.”

At the hospital, the deputies hoped against hope that the baby would pull through.

When screaming and crying erupted from the room where Autumn’s family was waiting, the deputies didn’t have to ask what happened. And the emotions they had been beating back in order to do their jobs started to flow.

“What sticks to me is seeing her in that state, and it’s the age – the fact that she looked like a 1-year-old, like a baby, like a toddler,” Eguia said. “She was so young, and she was suffering from a gunshot wound, which should not ever happen.”

In an interview at the Compton Sheriff’s Station on Saturday, Eguia, 38, who is stocky with friendly brown eyes, seemed at ease discussing his feelings. Raygoza, 35, broad-shouldered with a shaved head, was more reticent.

Neither is a father, but both have young nieces and nephews.

After Autumn was pronounced dead, the deputies returned to the scene to help their colleagues.

******

Rushing a victim to the hospital in a patrol car is known as a “grab and run,” explained Cmdr. Keith Swensson, a department spokesman who previously was in charge of Lakewood Station.

Swensson said the option, which he has used about a half-dozen times during his career, is typically reserved for babies or injured deputies.

Most of the babies are not victims of violence but are choking or have stopped breathing, Swensson said.

Capt. Myron Johnson, who runs Compton Station, said his deputies probably made the right decision by not waiting for the paramedics.

He has offered them time with grief counselors, and he is observing them to make sure their work isn’t affected. Children’s deaths can be especially traumatic: Johnson still remembers the little ones who lost their lives over two decades ago when he was a deputy in Carson.

“Those are the visuals that you never forget,” said Johnson, a 28-year veteran of the Sheriff’s Department. “I can account for each one. I can tell you about the circumstances and the grief-stricken parents. It’s still very vivid.”

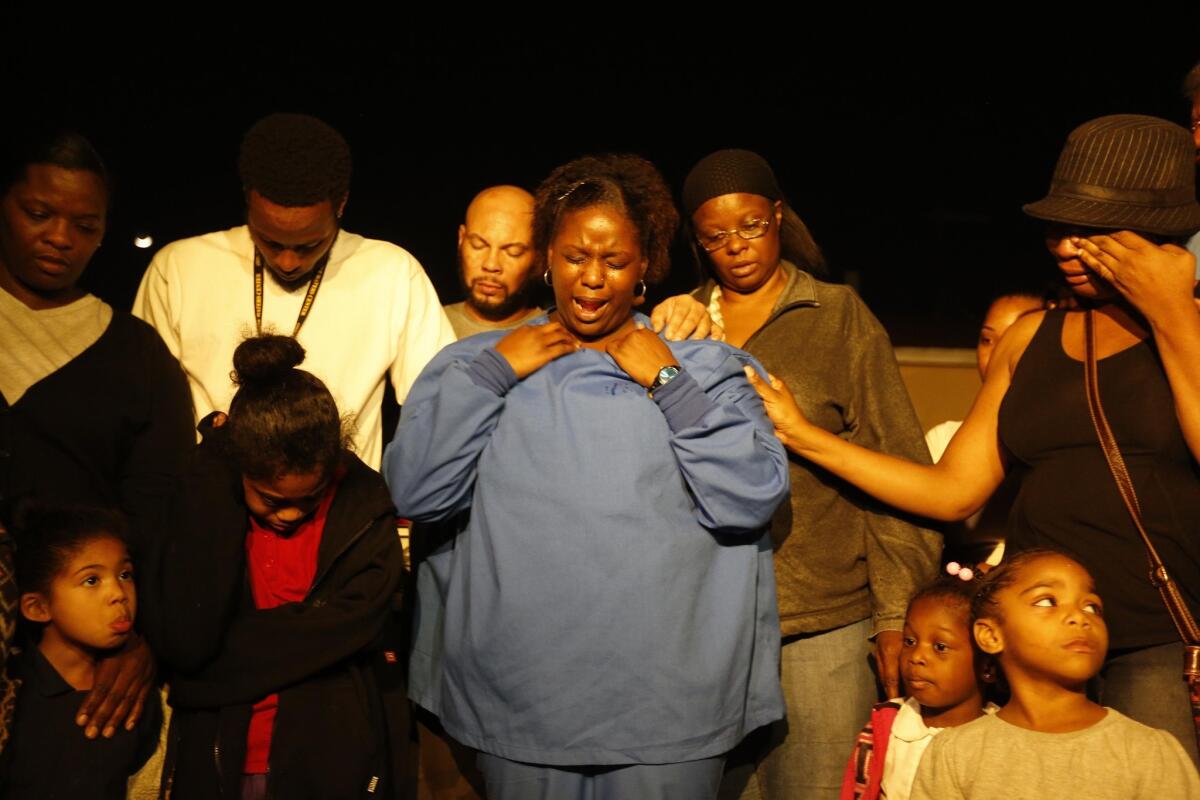

Autumn Johnson’s cousin, Raeshon Garcia, leads the family in prayer Feb. 10.

For Raygoza, Autumn’s death was an initiation. It was only the second gunshot killing he has worked. He was just getting comfortable with the tightrope act of driving with “lights on, sirens on.”

“Throughout the day, you replay it a lot in your head. It just comes and goes,” Raygoza said. “You just think how unfortunate it is, and there’s just a sadness that comes over you. There was a child that didn’t have a chance to live a long life.”

Eguia, too, is haunted by flashbacks of the baby’s face, the car ride with her father, her family’s grief.

“There are things that I’ve seen out here that I’ll remember until hopefully I’m old, old, old,” Eguia said. “There are good things too, because there are a lot of good people in this city. ... Unfortunately, I see bad things that I’ll never forget, ever, that’ll stay with me forever.”

Twitter: @cindychangLA

The Homicide Report: A story for every victim >>

ALSO

City Council members grill LAPD brass on crime spike, police response

Chinese teens to be sentenced in kidnapping and assault of fellow ‘parachute kid’

Grim Sleeper serial killer trial begins, years after slayings terrorized South L.A.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.