Taking advantage of a second chance

- Share via

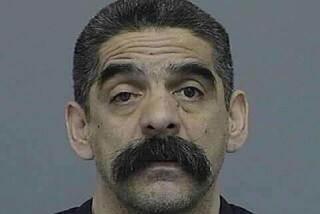

Before this week, the last time I’d seen Obed Silva was in an immigration court in downtown L.A. On that day, he rolled his wheelchair to the witness box and explained to a judge why he shouldn’t be deported.

That was in 2009. Born in Mexico but raised in Orange County, Silva is a 32-year-old former gang member paralyzed from a gunshot injury who reinvented himself as a scholar. It was the errors of his youth — as a teenager he shot and wounded a man at an O.C. party — that led to the deportation proceeding.

Professors at his alma mater, Cal State L.A., testified in immigration court on his behalf. After I told his story in this column, even a conservative talk-show host said he deserved to stay in the U.S. And in December, the government agreed to stop the deportation proceedings against him.

After nearly four years of court dates and adjournments, Silva’s final appearance before a judge lasted only a few minutes, he recalled. “Next thing I knew, the judge said, ‘You’re free to go.’”

This week Silva and I met again, at his mother’s home in Buena Park. I’d come to see what he was doing with his second chance.

He’s teaching writing at Cypress College and tackling his own painful story in a book. Much of his manuscript is about another man born in Mexico, a heavy drinker who was deported many years ago, and who isn’t missed on this side of the border:

Obed’s father, the late Juan Silva.

Juan Silva was, as Obed writes, “an alcoholic, a drug-addict and a wife beater.” Juan Silva, aged 48 at his death, was one of those fraught men who live hard and leave a lifetime of wreckage in their wake.

“I came to this country to run away from him,” Obed’s mother, Marcela Mendoza, told me. Juan Silva was, by Mendoza’s account, obsessed with the family that had escaped him. Soon after they left, he followed them northward.

Sober, Juan Silva could be charming and generous. Once he showed up in L.A. and showered his small son with expensive presents. Another time he forcibly took Obed from his mother and then returned the boy a week later, admitting he was unable to take care of him.

“He’d become desperate when I got away from him,” his mother said.

Silva was not yet in grammar school when his father was arrested in Texas — for drug dealing, the family suspects — and deported from the U.S.

Once a talented painter, Juan Silva slowly drank himself to death back in Mexico, one 32-ounce bottle of Carta Blanca beer at a time, indulging in an alcoholic’s sense of his own grandiosity. Here in California, his son Obed was nearly getting himself killed on the streets of the O.C., armed and in search of the “glory” of a street “warrior.”

“His genes are really strong,” Obed told me. “We’re so similar, it’s frightening.”

Now, slowly and methodically, Obed is trying to untangle this story and create art from it.

Silva has a master’s degree in medieval literature. In his memoir, his prose shifts back and forth from the erudite to the raw, from angry to contemplative. He describes humiliating his father once with a Spanish cuss word, then riffs on the word’s medieval origins, with a bit of Chaucer thrown in for good measure.

“I’m learning about myself and my own problems,” Silva told me of the writing process. “Even from a distance, from across the border, my father not being around and being an alcoholic affected me.”

“Father, why can’t I cry for you?” Silva writes, describing his emotions as he wheeled toward his father’s casket at a Chihuahua, Mexico, funeral home last year.

“Tell me: How was it when you left? I keep thinking that you simply closed your eyes; that you were tired and just gave up — peacefully.... No more beers. No more pain.... The alcohol on your breath was your last smell.”

Reading Obed’s account of his father’s life and death, and listening to his mother’s often frightening encounters with Juan Silva was a lesson in the complexity of the immigration story.

Juan Silva’s violent behavior, and Mendoza’s desire to escape him, created an American family.

Immigration is entering into a relationship with another set of people — with all their complex histories. Sometimes the “good” and the “bad” immigrants come tagging along with each other.

Obed was a baby when his mother first crossed the border, and he now speaks and writes in English as his native language. Obed and his mother were not seeking riches or even economic comfort when they came here, but rather something more basic: peace and safety.

Mendoza gave her son a home to return to when his life spun apart. And also a love of learning and books. In the three hours I spent in their home this week, they discussed the books that carried them through hard times, including “Angela’s Ashes,” “Les Miserables,” and “Siddhartha.”

“I’m so lucky I’m my mother’s son,” Silva told me. “If I had another mother, I’d probably be on the streets following in an alcoholic’s footsteps.”

I’m proud of my government for the compassion it showed in giving Obed Silva a second chance. I wouldn’t expect anything less from the U.S. — we are, after all, a country founded by people seeking second chances.

By allowing Silva to stay in the U.S., we gained an American writer, a thinker, a survivor and an example of redemption.

And yet, by deporting his father decades ago, the U.S. government gave Silva and Mendoza a chance to live in peace. It protected them with the fair and just application of our laws.

In his memoir-in-progress, Silva describes the surprisingly saintly look of his father’s corpse as Silva finally wheels up to it and studies it up close.

“All the harm had been done,” Silva writes. “Daddy could do no harm no more.”

Afraid of his father no longer, Obed Silva pulls the Plexiglas cover off the casket and unbuttons the corpse’s shirt to see the tattoo he knows to be there. He takes one last look at the two names etched, in faded ink, on Juan Silva’s chest:

Marcela y Obed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.