Church Markets Its Gospel With High-Pressure Sales

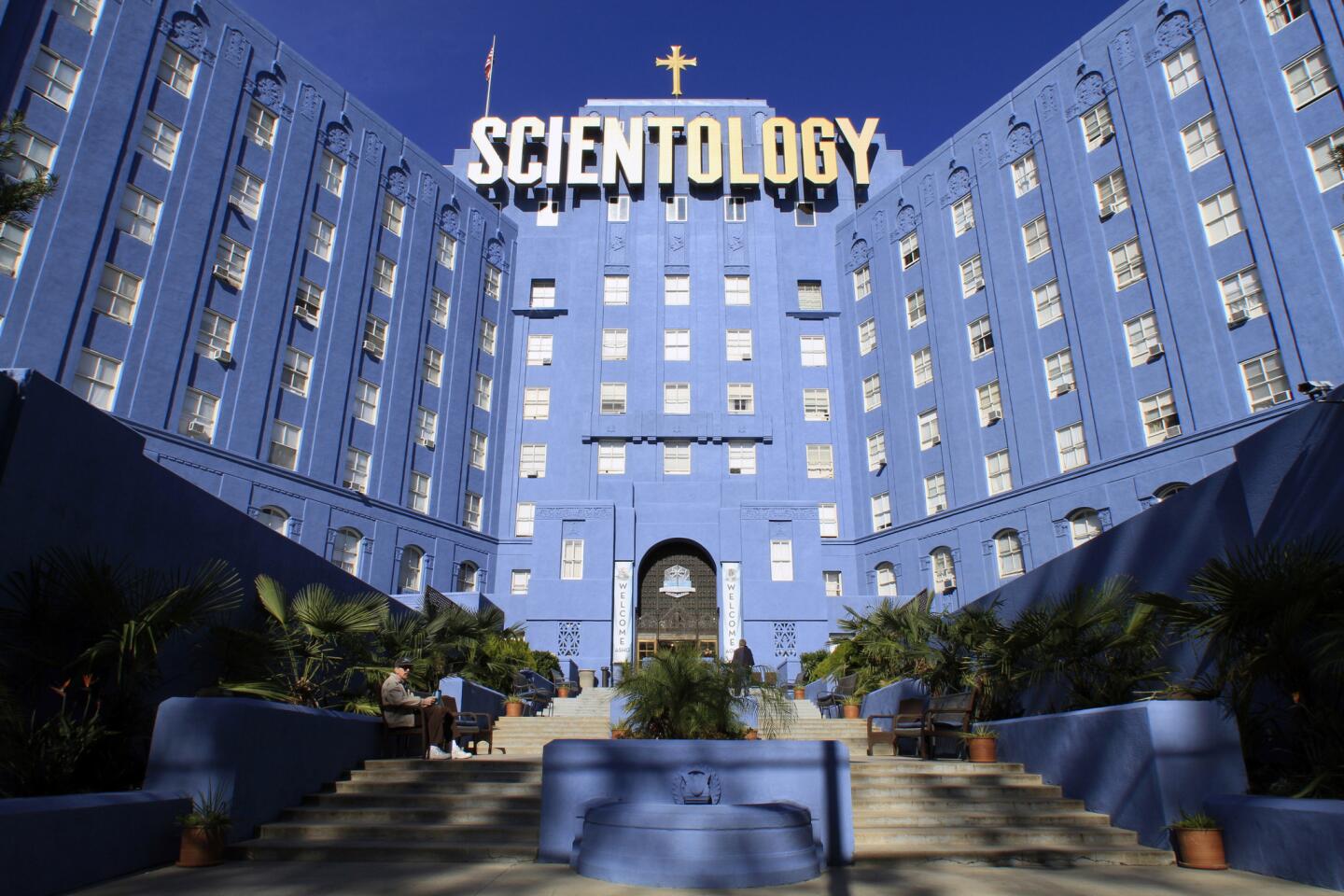

Behind the religious trappings, the Church of Scientology is run like a lean, no-nonsense business in which potential members are called “prospects,” “raw meat” and “bodies in the shop.”

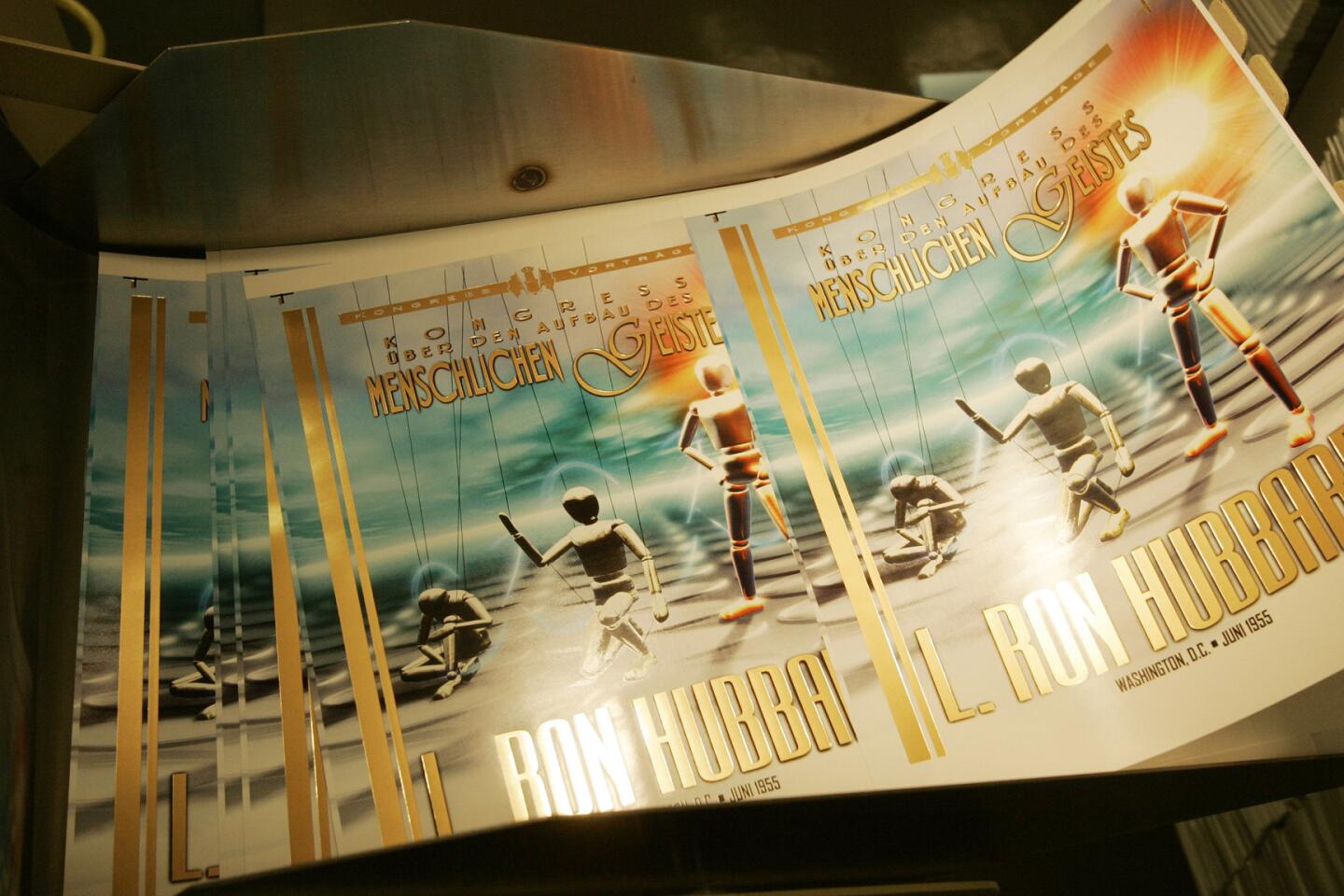

Its governing financial policy, written by the late Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, is simple and direct: “MAKE MONEY, MAKE MORE MONEY, MAKE OTHERS PRODUCE SO AS TO MAKE MONEY.”

The organization uses sophisticated sales tactics to sell a seemingly endless progression of expensive courses, each serving as a prerequisite for the next. Known collectively as “The Bridge,” the courses promise salvation, higher intelligence, superhuman powers and even possible survival from nuclear fallout--for those who can pay.

Church tenets mandate that parishioners purchase Scientology goods and services under Hubbard’s “doctrine of exchange.” A person must learn to give, he said, as well as receive.

For its programs and books, the church charges “fixed donations” that range from $50 for an elementary course in improving communication skills to more than $13,000 for Hubbard’s secret teachings on the origins of the universe and the genesis of mankind’s ills.

The church currently is offering a “limited time only” deal on a select package of Hubbard courses, which represent a small portion of The Bridge. If bought individually, those courses would cost $55,455. The sale price: $33,399.50.

As a promotional flyer for the discount observes, “YOU SAVE $22,055.50.”

To complete Hubbard’s progression of courses, a Scientologist could conceivably spend a lifetime and more than $400,000. Although few if any have doled out that much, the high cost of enlightenment in Scientology has left many deeply in debt to family, friends and banks.

Ask former church member Marie Culloden of Manhattan Beach, who describes herself as a “recovering Scientologist.”

“I’m trying to recover my mortgaged home,” says Culloden, who spent 20 years in Scientology and obtained three mortgages totaling more than $80,000 to buy courses.

The Scientology Bridge is always under construction, keeping the Supreme Answer one step away from church members--a potent sales strategy devised by Hubbard to keep the money flowing, critics contend.

New courses continually are added, each of which is said to be crucial for spiritual progress, each heavily promoted.

Church members are warned that unless they keep purchasing Scientology services, misery and sickness may befall them. For the true believer, this is a powerful incentive to keep buying whatever the group is selling.

Through the mail, Scientologists are bombarded with glossy, colorful brochures announcing the latest courses and discounts. Letters and postcards sound the dire warning, “Urgent! Urgent! Your future is at risk! . . . It is time to ACT! NOW! . . . You must buy now!”

By far the most expensive service offered by Scientology is “auditing”--a kind of confessional during which an individual reveals intimate and traumatic details of his life while his responses are monitored on a lie detector-type device known as the E-meter.

The purpose is to unburden a person of painful experiences, or “engrams,” that block his spiritual growth, a process that can span hundreds of hours. Auditing is purchased in 12 1/2-hour chunks costing anywhere between $3,000 and $11,000 each, depending on where it is bought.

Even Scientology’s critics concede that auditing often helps people feel better by allowing them to air troubling aspects of their lives--much like a Catholic confessional or psychotherapy--and keeps them coming back for more.

The church makes no apologies for the methods it uses to raise funds and spread the gospel of its founder. Scientology spokesmen said in interviews that it takes money to cover overhead expenses and to finance the church’s worldwide expansion, as it does for any religion.

“You can’t do it on bread and butter,” said one.

Church leaders will not discuss Scientology’s gross income or net worth. But they contend that Scientologists who pay for spiritual programs are no different from, say, Mormons who tithe 10% of their income for admittance to the temple, or from Jews who buy tickets to High Holiday services or from Christians who rent church pews.

“The fact of the matter is that the parishioners of the Church of Scientology have felt and continue to feel that they get full value for their donations,” said Scientology lawyer Earle C. Cooley.

Many Scientologists say that Hubbard’s teachings have resurrected their lives, some of which were marred by drugs, personal traumas, self doubts or a sense of alienation. They say that, through the church, they have gained confidence and learned to lead ethical lives and take responsibility for themselves, while working to create a better world.

Scientology “works,” they say, and for that, no price is too high.

“It takes money,” acknowledged Scientologist Sheri Scott. “It took money for my father to buy his Cadillac. I wish he’d sell the damn thing and give me the money (for Scientology). . . . I have never felt cheated at all.”

“I’m not glued to the sky or anything. I’m a very normal person,” she added. “I just wish more people would take a look, would read (about Scientology), before they decide we’re cuckoo.”

While other religions increasingly advertise and market themselves, none approaches the Church of Scientology’s commercial zeal and sophistication.

Its tactics come directly from Hubbard, who wrote entire treatises on how to create a market for, and sell, Scientology.

He borrowed generously from a 1971 book called “Big League Sales Closing Techniques.” Touted as the “selling secrets of a supersalesman,” the book was written by former car dealer Les Dane, who has conducted popular seminars at Scientology headquarters in Florida.

Hubbard said Scientology must be marketed through the “art of hard sell,” meaning an “insistence that people buy.” He said that, “regardless of who the person is or what he is, the motto is, ‘Always sell something. . . .’ ”

Hubbard contended that such high-pressure tactics are imperative because a person’s spiritual well being is at stake.

Among other things, he directed his followers to: “rob the person of every opportunity to say ‘No.’ ”; “help prospects work through financial stops impeding a sale”; “make the prospect think it was his idea to make the purchase”; utilize the two man “tag team” approach, and “overcome and rapidly handle any attempted prospect backout.”

One of the most important techniques in selling Scientology, Hubbard said, is to create mystery.

“If we tell him there is something to know and don’t tell him what it is, we will zip people into” the organization, Hubbard wrote. “And one can keep doing this to a person--shuttle them along using mystery.”

Frequently, a person’s first contact with Scientology comes when he is approached by a staff member on the street and offered a free personality test, or receives a lengthy questionnaire in the mail.

Using charts and graphs, the idea is to convince a person that he has some problem, or “ruin,” that Scientology can fix, while assuaging concerns he may have about the church. According to Hubbard, “if the job has been done well, the person should be worried.”

With that accomplished, the customer is pushed to buy services he is told will improve his sorry condition and perhaps give him such powers as being able to spiritually travel outside his body--or, in Scientology jargon, to “exteriorize.”

Former church member Andrew Lesco said he was told that he “would be able to project my mind into drawers, someone’s pocket, a wallet and I would be able to tell what’s inside . . . “

Church members are required to write testimonials--”success stories”--as they progress from one level to the next.

The testimonials regularly appear in Scientology publications. Usually carrying only the authors’ initials, they are used to promote courses without the church itself assuming legal liability for promising results that may not occur, according to ex-Scientologists. Here is an example:

“We were having trouble with the windshield wipers in our car. Sometimes they would work and sometimes they wouldn’t. . . . We were driving along, and my husband was driving. I got to thinking about the windshield wipers, left my body in the seat and took a look under the hood. I spotted the wires that were shorting and caused them to weld themselves together, like they were supposed to be. We haven’t had any trouble with them since.”

Scientology staffers who sell Hubbard’s courses are called “registrars.” They earn commissions on their sales and are skilled at eliciting every facet of an individual’s finances, including bank accounts, stocks, cars, houses, whatever can be converted to cash.

Like all Scientology staffers, a registrar’s productivity is evaluated each week. Performance is judged by how much money he or she brings in by Thursday afternoon. And, in Scientology, declining or stagnant productivity is not viewed benevolently, as former registrar Roger Barnes says he learned.

“I remember being dragged across a desk by my tie because I hadn’t made my (sales quota),” said Barnes, who once toured the world selling Scientology until he had a bitter break with the group.

Barnes and other ex-Scientologists say that this uncompromising push to generate more money each week places intense pressure on registrars.

Another former Scientology salesman in Los Angeles said he and other registrars would use a tactic called “crush regging.” The technique, he said, employed no elaborate sales talk. They repeated three words again and again: “Sign the check. Sign the check.”

“This made the person feel so harassed,” he said, “that he would sign the check because it was the only way he was going to get out of there.”

A 1984 investigative report by Canadian authorities quoted a Toronto registrar as saying that members of the public want to be “bled of their money. . . . If they didn’t, they would be staff members eligible for free training.”

The Canadian report also recounted a meeting during which Scientology staffers chanted: “Go for the throat. Go for blood. Go for the bloody throat.”

Former Scientologist Donna Day of Ventura said that church registrars accused her of throwing away money on rent and on food for her cats and dogs--”degraded beings,” they called her pets. They said the money should be going to the church.

“I was so upset, I finally left the house with them sitting in it,” said Day, who sued the church to get back $25,000 she said she had spent on Scientology.

Several years ago, church members persuaded a Florida woman to turn over a workers compensation settlement she received after the death of her husband, Larry M. Wheaton, who left behind two children, ages 3 and 7. He was the pilot of an Air Florida jet that plunged into the Potomac River after it had departed Washington, D.C.’s National Airport in 1982.

The Wheatons were longtime church members.

Joanne Wheaton gave nearly $150,000 to the church and almost as much to a private business controlled by Scientologists. But the deal was blocked when a lawsuit was brought by an attorney appointed by the court to protect the children’s interests.

The suit claimed that the Scientologists had disregarded the future welfare and financial security of the Wheaton family by taking money that was supposed to be used solely for the support of the children and their mother.

After protracted discussions, the money was refunded and the Scientologists who negotiated the deal were expelled by the church for their role in the affair.

For years, one of Scientology’s top promoters was Larry Wollersheim. He traveled the country inspiring others to follow him across Hubbard’s Bridge. Then he became disenchanted with the movement.

In 1980, he filed a Los Angeles Superior Court lawsuit, accusing the church of subjecting him to psychologically damaging practices and of driving him to the brink of insanity and financial ruin after he had a falling out with the group.

Three years ago, a jury awarded him $30 million. The award was recently reduced to $2.5 million.

During the litigation, Wollersheim filed a 200-page affidavit in which he offered this analysis of what keeps Scientologists hooked:

“Fear and hope are totally indoctrinated into the cult (Scientology) member. He hopes that he will receive the miraculous and ridiculous claims made directly, indirectly and by rumor by the sect and its members.

“He is afraid of the peer pressure for not proceeding up the prescribed program. He is intimidated and afraid of being accused of being a dilettante. He is afraid that if he doesn’t do it now before the world ends or collapses he may never get the chance. He is afraid if he doesn’t claim he received gains and write a success testimonial he will be shunned. . . .

“How many people could stand up to that kind of pressure and stand before a group of applauding people and say: ‘Hey, it really wasn’t good.’?”

Wollersheim said that the courses provide only a temporary euphoria.

“Then you’re sold the next mystery and the next solution. . . . I’ve seen people sell their homes, stocks, inheritances and everything they own chasing their hopes for a fleeting, subjective euphoria. I have never witnessed a greater preying on the hopes and fears of others that has been carefully engineered by the cult’s leader.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.