Gang injunction splits a San Fernando Valley community

- Share via

Daniel, 15, lives on a tree-lined street at the northern tip of the San Fernando Valley.

It is a place of whiplashing contradiction. In one direction there are elegant Craftsmans, their roots as deep as the area’s historic olive groves, and tidy cul-de-sacs with driveway basketball hoops. In the other there is a poor, old-world barrio -- barren lots overtaken by weeds, a tiny house with a hand-painted sign hung from a coat-hanger that reads: “RANCH EGGS.”

Daniel is no less confounding.

Around his neck, he wears a cross etched with the words of the Lord’s Prayer. He is spellbound by narrative writing and excels in martial arts and Aztec dancing. Still, he has become numb to violence and crime. A gang, San Fer, has long defined his neighborhood’s cultural and social structure. His father, a gang member, is in prison; his uncle was shot dead, by another gang member.

Daniel has been in trouble -- for poking a kid with a stick, for possession of a cigarette. He is not a gang member, but lately, he has looked the part -- oversized T-shirts; baggy jeans.

By the time he went out with friends one night last week to tag houses with graffiti, he was at a crossroads.

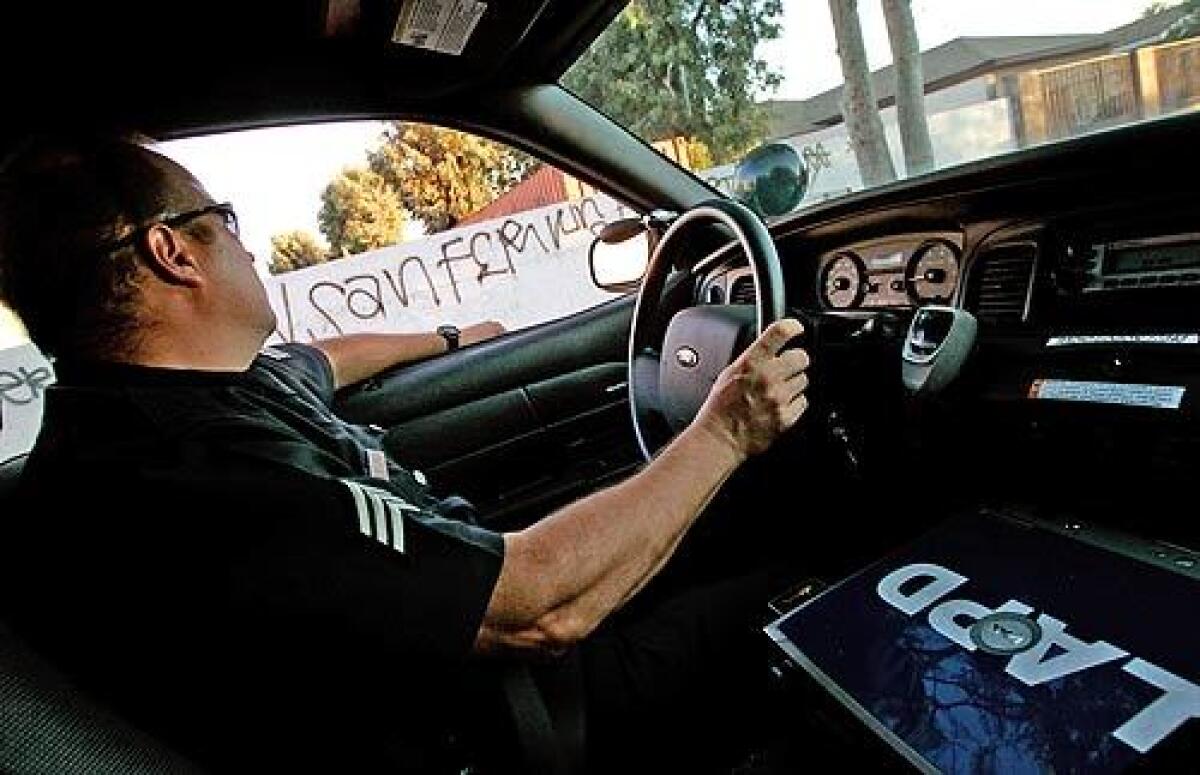

This summer, law enforcement officials enacted an injunction targeting San Fer. It is the 37th gang injunction in Los Angeles and the largest yet, covering nearly 10 square miles in Sylmar and San Fernando, and it has left a troubled community deeply divided.

San Fer began decades ago as a protectorate for farm laborers.

Today, the gang’s members -- an estimated 900 or 1,000 people -- extort “rent” from businesses, steal cars and deal drugs, officials say. It also has ties to the Mexican Mafia, a “super gang” that has charged San Fer with collecting “taxes” from second-tier gangs.

“This is a big gang covering a big territory,” said Bruce Riordan, the Los Angeles city attorney’s director of anti-gang operations. “They have quite a bit of muscle.”

Through the injunction, authorities effectively “sue” the gang on behalf of the public, restricting members’ activity. Members, for instance, are prohibited in many cases from associating with each other in public and from visiting places that have been used in the past for planning or recruitment.

The injunction brought a wave of police attention, and Daniel might have been wise to remember that when a friend handed him a can of baby-blue spray paint. (The Times is withholding his last name because, his family said, expressing ambivalence about the gang could endanger him.)

First, Daniel considered painting his nickname, but then thought his friends would find that “stupid.” He decided to paint the name of the area where he lives, which he shortened to the name of the gang that had defined so much of his life: “San Fer.”

“A mistake,” Daniel said.

A squad car pulled up. Daniel, eager to establish street credibility, did not run. By the end of the night, he was sent home with papers indicating that he could be a target of the gang injunction. A relative who raised him said she fears this could be the moment that pushes Daniel down the wrong path.

Gang injunctions come with daunting complexities in communities where a criminal enterprise has touched thousands of people -- many of whom are not hard-core criminals or gang members themselves.

What should be done about teenagers who identify with a gang but do not participate in its criminal activities? If a gang spans generations, like San Fer, should an uncle be prohibited from speaking with his nephew if both are gang members? Officers are forced to make difficult judgments on the fly, Riordan said. “Is someone meeting a family member because of something legitimate? Because they are going to church?” he asked. “Or because of something else?”

Authorities have attempted to inject safeguards against overreaching.

The San Fer injunction is the first, for instance, in which suspected gang members are given papers not only “serving” them, but telling them how to challenge their inclusion if they feel they have been wrongly accused.

Prosecutors have also begun using, without legal obligation, a greater burden of proof to target new gang members.

“We are seeking a balance,” Riordan said, “between aggressive prosecution . . . and enlightened enforcement.”

Many local residents are hailing the injunction as a new chapter for a pocket of the Valley that they feel is a forgotten piece of the metropolis.

“If this is going to help put more officers in the area, I’m all for it,” said Jeanne Rowe, 82, a civic activist and an accountant who recently completed her 46th year of tax preparations. “If they need more help in doing their job, I’m all for it.”

But not everyone is -- not by a long shot.

At community meetings this year, critics have complained that the injunction is heavy-handed and broad, criminalizing, in a sense, an entire community.

“What is going on here is very unjust. Just because people are scared does not make it right,” said Luis Rodriguez, whose home is inside the injunction boundaries.

Rodriguez, 54, was a member of a South San Gabriel gang, an association that left him imprisoned and addicted to heroin.

He became a journalist, then a writer. He is the author of “Always Running,” a memoir about his gang years and a cautionary tale for his son, which has sold more than 300,000 copies.

Rodriguez works with at-risk young men, some of whom have had association with gangs. Targeting them through law enforcement when there is no evidence that they have committed a specific crime, he said, shows a lack of imagination.

“If these kids are sitting around the park in Sylmar with nothing to do, that’s because there is nothing for them to do,” he said. “We can save these kids. But the way this thing is set up, if the gang doesn’t get you, the police will.”

Some residents have complained that property values could be hurt by a blanket declaration of gang activity. Kevin Godley, a real estate agent who sells houses in the area, noted that financial institutions often rely on agents to establish base prices -- and that agents are expected to list a gang injunction as a factor in assessing value.

“There will be a stigma,” he said. “Even if it gets cleaned up, there will be a stigma.”

The result is two strikingly different portraits of the same community.

In court documents filed to support the injunction, officials described a “reign of terror” perpetrated by the gang -- and a community where residents are “virtual prisoners in their own homes.”

Many residents say that does not sound like the community where they live.

Sylmar Park, for instance, was described in the documents as having been seized by San Fer -- “claimed,” the documents state, “as theirs.”

But this summer, 60 children a day attended camp there, without incident. There are year-round programs -- the usual mix of soccer, softball and other sports leagues, many with waiting lists.

“This is a nice community,” said Los Angeles City Councilman Richard Alarcon. “It has been cast as a war zone.”

Caught in the middle of two competing images, residents say, are young men, many of whom now try to avoid simply walking down the street.

Back at Daniel’s house, his grandmother said she began lighting candles and praying for him every night after his latest encounter with the police.

Every time it happens, she said, it seems to fuel his anger.

Even before the spray-painting incident, an officer stopped him for riding his bike without a helmet. The officer pulled up Daniel’s shirt to see if he had tattoos, then asked him if he was a meth addict because of his acne.

“He has acne,” his grandmother said, “because he is 15 and eats too much fast food.”

After that encounter, Daniel shaved his head -- knowing that it made him look more like a gang member, making it more likely that he might be stopped by police again.

At his school, there are kids from other nearby communities who associate with different gangs. What if they learn that he has been targeted through the injunction? Would Daniel, his grandmother asked, then join the gang to protect himself -- joining, in effect, because he was accused of being in one?

She smiled, realizing that she was talking in circles.

“Do you know that when someone gets pregnant here, we pray that it is a girl?” she said quietly. “That’s because boys here go to war.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.