PHOTOS: The wide-ranging roots of the Mozingo family tree

Joe Mozingo explores the creek near Warsaw, Va., where his forebear, Edward Mozingo, grew tobacco and raised livestock as a tenant farmer after suing for his freedom in 1672. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

In Virginia, Mozingo Road intersects with Oak Row Road amid the forests and farms where Mozingos have lived for centuries. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Locust Grove is a colonial plantation in Virginia’s Northern Neck that has remained virtually unchanged for more than three centuries. It’s still owned by the family Edward Mozingo worked for in the 1600s. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

A slave house remains virtually intact at Locust Grove, a 348-year-old plantation in Walkerton, Va. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A flag blows in the breeze along Menokin Road near Warsaw, Va., a historic area where farmers grow barley, corn and tobacco. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

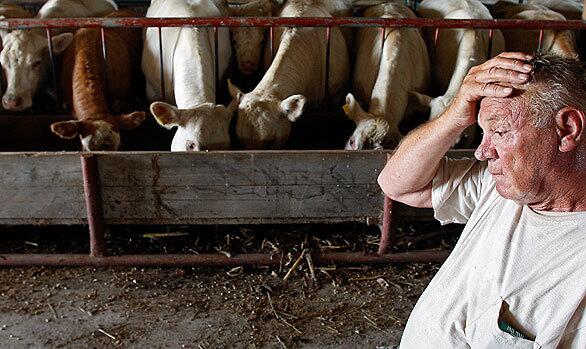

Junior Mozingo, a retired textile mill worker, breeds hunting dogs in Virginias Northern Neck. He never asked his older relatives about his familys origins. “They didnt talk about it and we didnt ask.” (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Junior Mozingo and his grandchildren feed and water hunting dogs at their farm in the Northern Neck of Virginia. Did he ever wonder about the name Mozingo? “Its Italian, isnt it?” he asked. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Rhodie Mozingo, whose family has lived in Virginias Northern Neck since the 1600s, walks past his grandmothers grave at Menokin Baptist Church. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

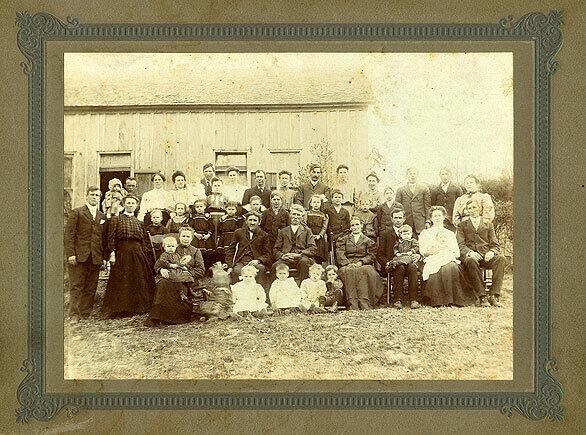

Edwin and Nancy Mozingo, forebears of many of the Mozingos now living in Decatur County, Ind. They are Bud, Stan and Amys grandparents. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Joe Mozingo floats in a creek that runs through a deep hollow in the countryside around Greensburg, Ind., a place blessed by pastoral beauty. Along such creeks and their pools of polished stones, local residents -- including the Mozingos --- have held their baptism rituals for more than 150 years. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

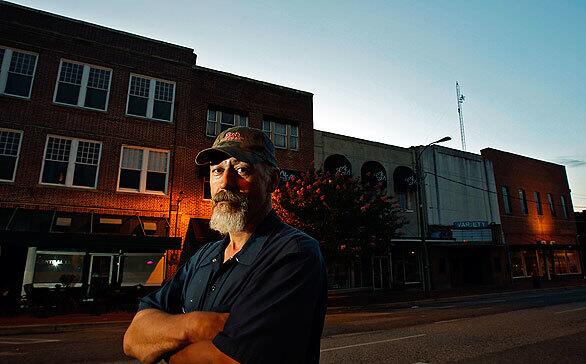

Bud Mozingo calls himself the “patriarch” of the Mozingos who have settled in the rural region around Greensburg, Ind. Few black people make this part of the Hoosier State their home. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Indiana relatives of Bud and Amy Mozingo. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

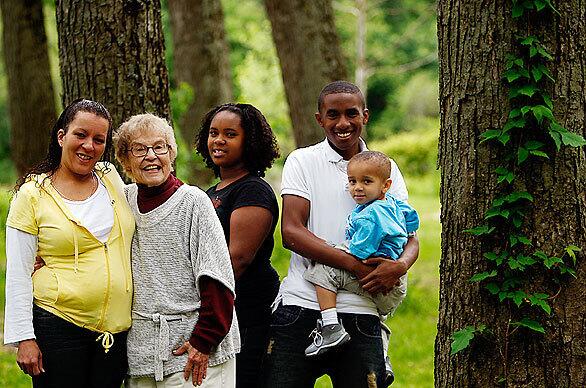

Amy Osting with her granddaughter Tanya Turner, left, and great-grandchildren. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Bud Mozingo stands beside the fence that fronts his property on the outskirts of Greensburg, Ind. He bought a large lot of shoes at a yard sale only to find out that most did not have pairs. Rather than throw them out, Mozingo nailed the shoes to the fence posts, which have become a local curiosity. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

A creek runs through the forest near Westport, Ind., a rural area southeast of Indianapolis where Spencer Mozingo’s descendants moved. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Storm clouds make a curious formation above a barn in Westport, Ind., where members of the Mozingo clan have lived since the 1830s. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Cars cross a covered bridge in Westport, Ind. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Wiley Mozingo plays with his 2-year-old grandson at home in Dudley, N.C. When the state’s schools desegregated in the mid-1960s, Wiley enrolled in what had been an all-white high school. He endured taunts and racial slurs and often got into fights over the harassment. But he endured and became a star linebacker for the Southern Wayne High School football team. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Dwight Mozingo shows off a tattoo that he got while in the military. The younger brother of Wiley Mozingo, Dwight has a much lighter complexion. Lighter skin afforded a certain status in the Old South, and Dwight’s grandfather all but banished his dad from marrying a woman he deemed too dark. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Ricky Mozingo is the youngest of the Mozingo brothers who live around Goldsboro, N.C. He also has the lightest complexion and now identifies himself as more white than black. “Growing up, it felt like I got dropped off in the wrong neighborhood....I kind of felt like a mistake for a long time,” he said. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A woman takes refuge from the afternoon sun in an open-air structure that once served as the slave market in Fayetteville, N.C. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

The building that long ago served as the slave market in Fayetteville, N.C., sits inside a heavily traveled traffic circle in the middle of town. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

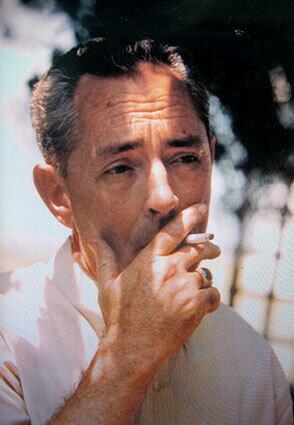

Times reporter Joe Mozingo’s grandfather, Joe, smoking on the back porch of his home in Studio City in the early 1960s. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

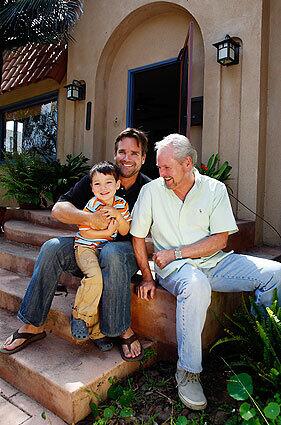

Joe Mozingo plays with his son Blake, 4, at Belmont Shore in Long Beach. He wants his children to know about their ancestry. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Joe Mozingo, left, with his son, Blake, 4, and his father, Dave. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)