Chatsworth train crash survivor has a long road back

- Share via

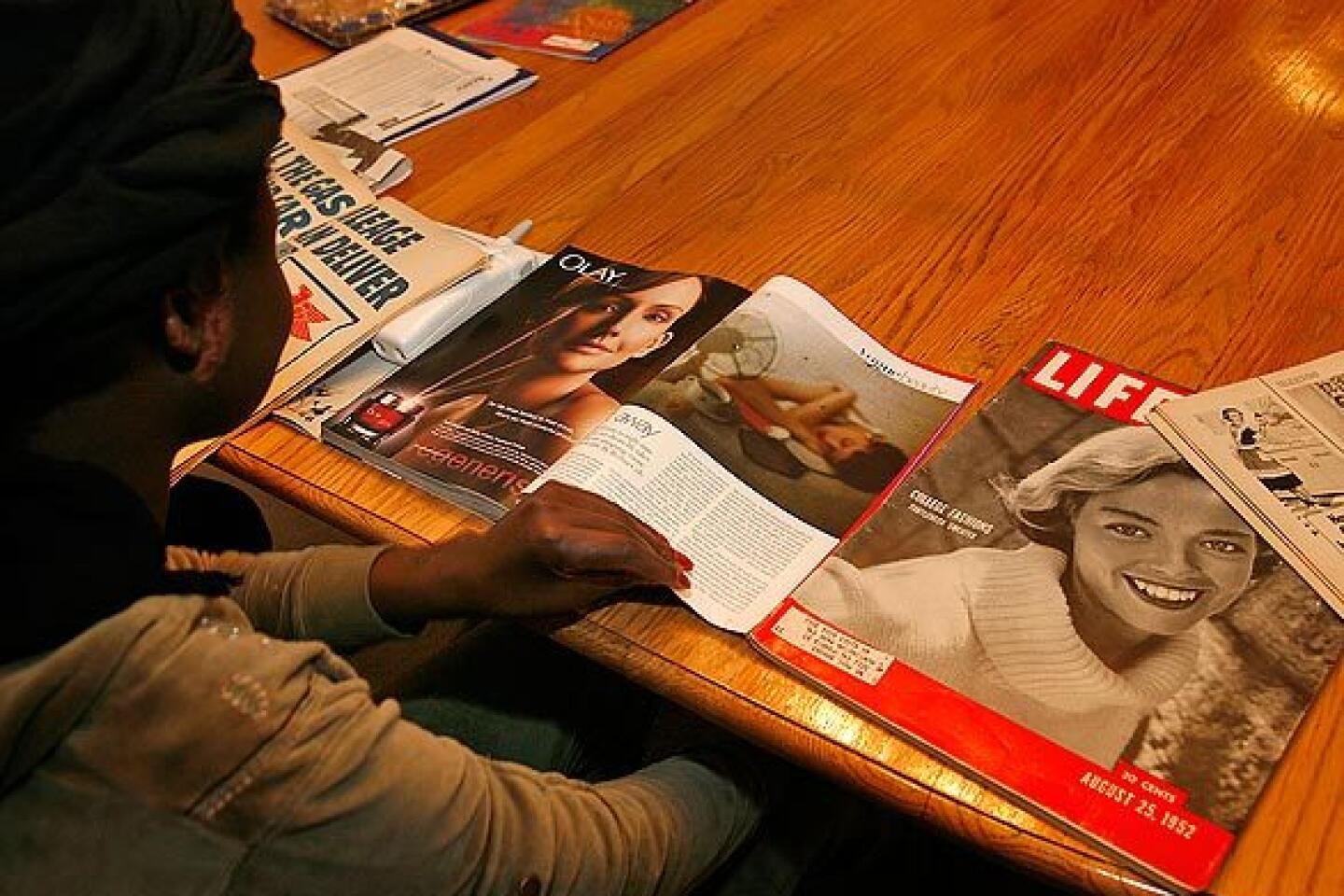

Racheal Mofya sits quietly, her head down, there but not there.

Her left arm rests in a sling. She scratches at the healing scars all over her body. A plum-colored turban hides the thick, livid scars snaking around her head.

Mofya is in a gaily decorated conference room at Los Angeles County-USC Hospital for a ceremony to honor the survivors of car crashes, gang shootings and freak accidents. They had come to the trauma center near death and, improbably, had survived. As each former patient makes his or her way to the podium, he or she is applauded.

But a hush fills the room when Racheal Mofya’s name is called.

Mofya was sitting in the first car of Metrolink 111 when it slammed head-on into a Union Pacific freight train in Chatsworth on Sept. 12, killing 25 and injuring 135.

She had so many injuries, said her surgeon, Dr. Ramon Cestero, that it reminded him of tending wounded soldiers in Iraq. She had broken bones, internal cuts, a torn cornea and burns over a tenth of her body. Worst was the head wound that kept her in a near-comatose state for two months.

As Mofya grips the table in front of her and pulls herself slowly to her feet, Cestero tells the gathering: “She had so many injuries that many didn’t think you were going to make it.”

The petite 27-year-old slowly shuffles to the podium unassisted. Given the microphone, Mofya simply whispers, “Thank you,” and turns around to make the long walk back.

Mofya faces many more months of physical and mental rehabilitation to regain the ability to walk, read, write and speak easily. Doctors still can’t say if the Zambian exchange student, who was a week away from a business degree when the crash occurred, will ever fully recover.

Quiet but bright

That Mofya was on the Metrolink train was a confluence of opportunity and luck.

The youngest daughter in a family of eight, she was raised in Lusaka, the largest city and capital of Zambia in south-central Africa. Mofya was a quiet but bright girl, studious and eager to make something of herself.

“She was a very smart kid,” said her older sister, Martha, who is studying nursing in Minneapolis. “She’s been always an ‘A’ student.”

Mofya and her siblings were among the more fortunate of citizens of Zambia, where 73% of the people live below the national poverty line.

Her salesman father and teacher mother were part of a burgeoning middle class, able to send their children to school, provide a modest home and serve regular meals.

But life was not always easy. Their mother died from malaria in 1985 and, less than a decade later, their father succumbed to an intestinal illness, Mofya’s sister said.

Mofya was undeterred. She received a bachelor’s degree in natural resources management at the University of Zambia. She was thinking about becoming a doctor, and had been accepted to medical school, when another opportunity unexpectedly came her way.

A Rotary International program aimed at creating jobs in Zambia was taking applications for students who wanted to study in the United States. Mofya saw it as a way to fulfill a dream of traveling and quickly wrote a business plan for a company that would produce products from honey, bee’s wax and a resin-like substance called propolis.

She and eight other applicants beat out 200 competitors. She heard about a business program offered by the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising and set her sights on enrolling at its Los Angeles campus.

Pat Abruzzese, a finance officer for a Chatsworth company that installs digital cabling, heard about Mofya through his Simi Valley Rotary club. She needed a home for a year, and, on the spot, Abruzzese offered it.

“She needed a room and we had one available,” he said. “It was as simple as that.”

Mofya arrived in fall 2007 and fit right in. She called Pat “Dad” and his wife, Joanne, “Mom” and developed a close bond with their children, Jaime, 21, and T.J., 17.

She took the train every day to the Fashion Institute in downtown Los Angeles. She earned straight A’s.

Like clockwork, she arrived at 7:32 each night at the Simi Valley station. Joanne Abruzzese would be waiting to pick her up.

When she wasn’t studying, Mofya, a devout Christian, hung out with friends from the Simi Valley church where the Abruzzeses worshiped.

“She was social but quiet,” said Nina Sampietro, who belonged to the same social group at Cornerstone Community Church. “She was just really excited about what she would be doing with her life.”

She planned to get her green card, work in the United States for a few years to save money and then return to Zambia.

Nina Woo, another church friend, said she was never boastful. “She would just say, ‘We’ll see where God has me.’ ”

Operating room

On Sept. 12, a Friday, Mofya boarded the 3:35 p.m. train at Union Station, intending to meet with her women’s Bible study group that night. At 4:23 p.m., the Metrolink and Union Pacific trains collided at a combined speed of 81 mph. Mofya’s car slammed into the locomotive, which tore more than halfway into it.

Within an hour, firefighters on top of the crumpled, smoking hulk extricated Mofya and gently handed her to rescuers on the ground, including Los Angeles Fire Department Capt. Denise Jones.

“You just go, ‘My goodness, how can a body go through this and survive?’ ” Jones said.

Mofya was loaded into a medevac helicopter. A team of trauma surgeons and nurses at County-USC Medical Center were waiting. She was in the operating room by 8 p.m., undergoing what would be the first of many procedures. Doctors tried to reduce the swelling in her brain and removed a portion that was severely damaged.

Later, she had pins installed in a badly broken ankle and femur. She underwent a corneal transplant.

On Nov. 19, she had a final surgery, skin grafts to repair burns to her scalp.

Her sister flew in the day after the accident and didn’t leave Mofya’s side for six weeks. The Abruzzeses came every day, and her church friends set up an around-the-clock rotation.

After more than two months in a coma-like state, Mofya spoke.

“She looked at me and said, ‘Mom, I hurt all over,’ ” Joanne Abruzzese recalled. Abruzzese called for a nurse, who thought she was kidding. “I said, ‘No really, she’s awake!’ ”

It was Thanksgiving Day.

Mofya spent four months at County-USC, and later, Northridge Hospital Medical Center, before being discharged Jan. 19.

Fourth-grade level

Mofya takes a few stiff-legged steps across the living room of the Abruzzeses’ comfortable, two-story home in Simi Valley.

Under the watchful eye of physical therapist John Noonan, she next works on the stairs.

On a living room table are a children’s reading book and a page of simple subtraction problems that Mofya completed earlier in the day. She reads and writes at about a fourth-grade level.

“She still laughs and goofs off with Jaime,” said Pat Abruzzese. “It’s kind of got back into the same pattern except she doesn’t stay with us on every topic like she used to. We do have to remind her what’s going on.”

Mofya sits quietly and smiles sweetly as she answers questions with a few words. If she is angered by what happened to her, she doesn’t let it show.

“I’m very happy to be home,” she says slowly, carefully picking each word.

Her doctors say it will take up to a year to determine how much permanent brain damage she suffered.

They recommended that she enter a special rehabilitation program for people with brain injuries at Northridge Hospital Medical Center. The hospital initially turned her down because she had exhausted the limits of her private student’s insurance and is covered by an emergency Medi-Cal health program, Joanne Abruzzese said.

The couple sparred with hospital officials for weeks, finally gaining admission after appealing to Northridge’s parent company, Catholic Healthcare West. Mofya began the program last week.

It’s only the latest battle for the Abruzzeses since Mofya’s accident. There have been endless forms to fill out, doctor’s appointments to get her to and the struggle to make sure she is never left alone.

Both Pat and Joanne Abruzzese hold full-time jobs, so they have enlisted help from paid aides, therapists and friends.

“It’s not a burden, but it does take time,” Pat Abruzzese said.

Martha Mofya visited recently and the two sisters fussed over a wig that Mofya was wearing and talked about their life back in Zambia.

Mofya says softly that she wants to go back.

But her plans have changed.

She no longer wants to start a skin-care business. She wants to help people with disabilities.

Her sister, sitting beside her, slips an arm around Mofya.

“Life is full of circumstances. It’s up to you how you challenge those circumstances,” Martha Mofya said. “Racheal’s up for the challenge.”

catherine.saillant

@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.