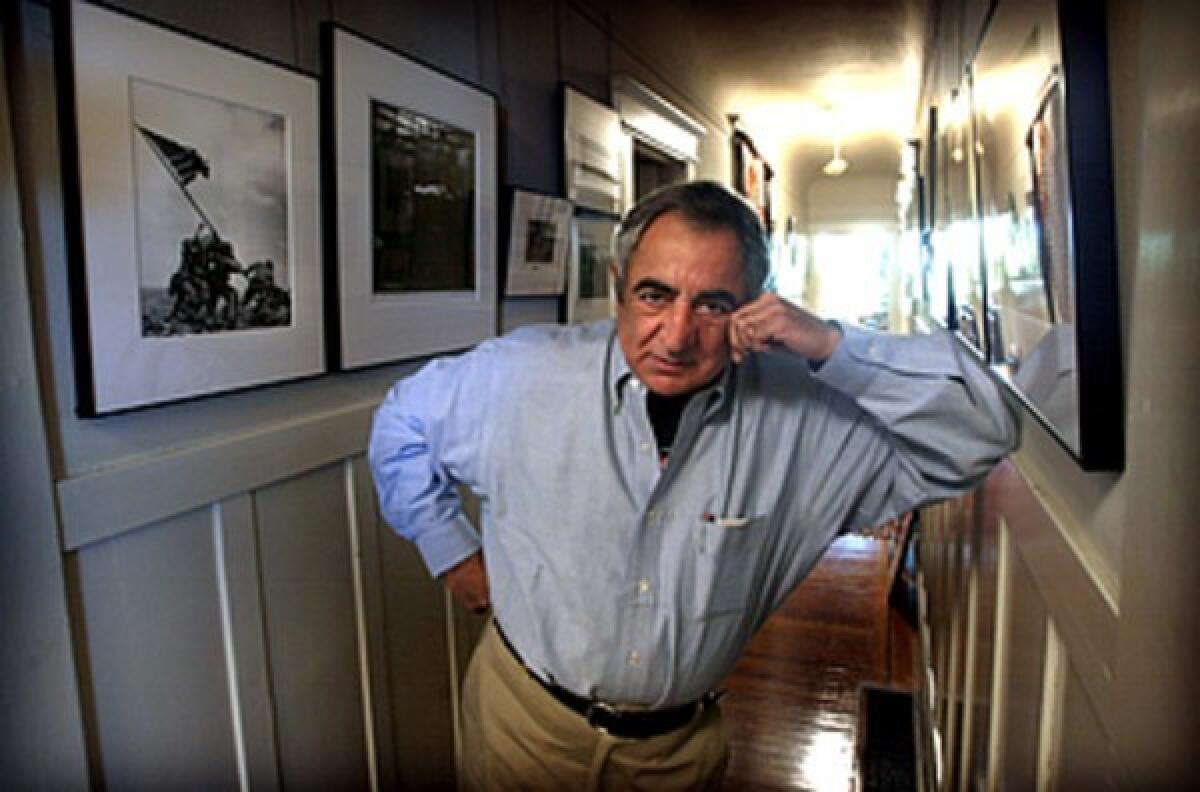

Jim Marshall dies at 74; iconic photographer shot music greats

Jim Marshall, celebrated in music circles for his iconic, attitude-laced images of Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, the Rolling Stones and other ‘60s rock luminaries as well as equally revered portraits of Johnny Cash, Miles Davis, John Coltrane and myriad folk, country, jazz and blues artists, died Wednesday in New York City. He was 74.

Marshall apparently died in his sleep while on a promotional tour for “Match Prints,” a new collection of similar shots taken across the decades by Marshall and Timothy White, a longtime devotee who referred to his mentor as “royalty in my line of work.”

Marshall’s most famous images, which wound up on more than 500 album and CD covers, in magazines, newspapers and on posters, include his shot of Hendrix setting fire to his electric guitar at the Monterey Pop Festival, Dylan rolling a tire down the littered streets of Greenwich Village on an early morning walk and Cash flipping his middle finger directly into the camera lens at San Quentin State Prison.

“I have always loved the photographs Jim Marshall took of my father, and more than any other, the photos of family and friends,” Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, told The Times in an e-mail Thursday. “Of course, the most famous photo Jim took of my father was the unforgettable ‘shoot the bird shot.’

“He magically captured my father’s energy and attitude at that time,” Cash noted. “This photo is a wonderful example of my father’s edginess and aggressive nature. But my father was so much more. The photos Jim took that mean the most are those which capture intimate, gentle heart and spirit -- both of my father and my mother. It is these I love the most.”

Marshall was always quick to explain that Cash was simply mugging for the camera. “It shows John’s individuality,” Marshall noted on his own website in an anecdote accompanying the photo, “but the gesture was definitely done in jest. John’s got a great sense of humor and this was not a serious shot.”

Marshall lived most of his life in San Francisco, where through a chance encounter in 1959 he snapped his first photograph of an important musician: jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, who had stopped him to ask for directions to Berkeley. That started Marshall on a career spent with pop musicians as well as other A-list entertainers, who often dropped their guard in his presence for the intimate portraits he favored.

He also worked the Woodstock and Altamont rock festivals in 1969, the Rolling Stones 1972 tour and was the only photographer allowed backstage at the Beatles’ final tour performance at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in 1966.

“All of these artists have given me their trust,” he told the Marin Independent Journal in November. “Trust given and trust received. And I’ve never violated that trust. I’ve never had a lawyer, a manager, an artist or an agent complain about a picture I used.”

Some of his career-making shots came during a two-year period in the early ‘60s when he moved to New York City, where the action was for photographers at the time. He captured Dylan, Joan Baez and other members of the folk music community just as their careers were starting to take off.

The shot of Dylan kicking the tire down the street, Marshall noted on his website, “was taken one Sunday morning when Bobby, his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, Dave Van Ronk and Terri Van Ronk were all going to breakfast in New York. Just two frames were shot -- no big deal -- but I feel it shows Bob was still a kid in 1963.”

James Marshall was born Feb. 3, 1936, in Chicago. The family moved to San Francisco when Marshall was 2, and he was raised by his mother after his father, a house painter, left the family when he was a boy.

Marshall raced cars as a high school student, dabbled in various jobs, including motor scooter salesman and insurance claims adjuster, but after serving a stint in the Air Force, he put a modest down payment on his first high-quality camera, a Leica M2, the brand he used throughout his life.

After that first shoot with Coltrane, he frequented San Francisco’s jazz and poetry clubs, moved briefly to New York, then returned to the Bay Area as the hippie culture was emerging.

During this period he got his famous photo of Joplin backstage, slouched on a couch with a bottle of Southern Comfort cradled in her hands.

“Some people said I shouldn’t have published that picture of her lying back, with the bottle in her hand, but I’ll defend it to the death,” he once said. “People said her legs looked too fat. But Janis said, ‘Hey, that’s a great shot because it’s how it is sometimes. Lousy.’ ”

But even his subjects’ approval wasn’t what motivated Marshall. It was the photo itself.

“You know, I don’t really care if Janis liked the picture or not; it was an honest, strong picture. A strong picture. It just happened that she liked it a lot.”

He accompanied Cash to his landmark 1968 Folsom Prison concert, which was covered for The Times by pop music critic Robert Hilburn, who kept in touch with Marshall frequently over the ensuing years.

“Besides being able to capture the spirit of artists, Jim also had the rare ability to know who to shoot -- i.e. to go after great artists, not just the most popular,” Hilburn said Thursday. “That’s why so many of his photos are still meaningful today: They document moments in the lives of great artists.”

At the time, gaining access to rock musicians wasn’t a problem for a photographer whose work had appeared in major publications.

Marshall opened the window to rock during one of its most creatively explosive, but also destructively hedonistic periods, and found himself seduced by the drugs that often went hand in hand with the music.

“There was a long, dark period fueled by cocaine,” Marshall said in 2005. “The ‘70s were fueled by cocaine and so were the ‘80s. It was a bottomless pit. So I just stopped. It was a matter of staying alive. I had ruined a lot of relationships with it, but fortunately, most of the good friends I have stayed with me.”

He reemerged in the 1980s and continued to shoot new generations of musicians, including the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Ben Harper and the Cult.

The first book of his photos came out in 1997: “Not Fade Away: The Rock and Roll Photography of Jim Marshall.” Others followed, including “Proof,” a 2004 collection of several dozen of his most-celebrated photos accompanied by the proof sheets of the shots that immediately preceded and followed them; “Jazz” in 2006; “Trust,” a 2009 volume of his color photography; and the new “Match Prints.”

He considered himself a photojournalist, not a celebrity photographer, and also spent time in the ‘60s documenting poverty in Appalachia and the civil rights movement.

No immediate family members survive him.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.