Dirty pools face a wave of closures

- Share via

Last week, a little boy plunged into a pool at an apartment complex in Highland Park. It was a warm day, and he was indulging in a ritual -- seeking relief in a refuge of cool bliss -- that plays out all over Southern California on such days.

But something was amiss.

The refuge of cool bliss was actually a pool of green, cloudy water. The water was so murky that the boy couldn’t find an object he was searching for at the bottom of the pool. He popped his head out and announced: “I still can’t find it.”

Such problems are not unusual.

A Los Angeles Times analysis of more than 16,000 swimming pools inspected by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health -- at places such as apartment buildings, hotels and motels, schools, condominium complexes and health clubs -- found that 10% were closed at least once by the agency over the last 3 1/2 years. (The analysis excludes pools in Pasadena, Long Beach and Vernon, cities that have their own public health departments and are not inspected by the county.)

Pools at apartment buildings and motels were closed at rates above the county average for all inspected pools.

Closures often occur because the water has turned cloudy or green, a sign that it lacks enough disinfectant. Such pools can easily spread bacteria or microscopic parasites that can cause illness.

Other reasons for closures by county inspectors include problems that may pose a risk for electrocution, or a broken, loose or missing cover for the pool’s main drain. A swimmer could stick an arm or leg in the drain, become trapped and drown.

Follow-up visits to six of the eight most frequently closed pools (at least five times since 2005, according to county records) by a reporter and photographers for The Times last week found three with murky or green water. Two had already been closed voluntarily by the apartment complexes’ managers, but that wasn’t the case at the Highland Riviera, a complex in Highland Park.

On June 24, a Times photographer saw the boy swimming in cloudy water. Julio Duran, an apartment manager, denied to a reporter that there had been any recent problems with the pool and described the water as clear.

In a subsequent telephone interview, Duran’s wife, Maria, who is also a manager, said she was unaware that the pool was murky. She said the pool had not been closed by the county for 18 months and said the earlier closures by the county were due to a tenant who tampered with an electrical panel that shut down the pool’s circulating system.

According to county records, the pool was last closed in September 2006. (Pools that are cited for closure are subject to reinspection days or weeks later. County inspectors closed the Highland Riviera pool March 29, 2005; April 25, 2006; Aug. 10 and 17, 2006; and Sept. 5 and 14, 2006. Reasons for closure included algae and cloudiness in the pool. Two of the official closures were imposed because inspectors were unable to gain access to the pool.)

Public health officials say that they try to inspect every pool once a year, but understaffing means visits come an average of every 18 months.

Most pools are clean most of the time, but under the wrong circumstances, water can become cloudy within a couple of hours, said Bernard Franklin, program manager for Los Angeles County’s Swimming Pool Program, which oversees more than 16,000 pools.

“You could come to a pool at 8 a.m. and it could be cloudy at noon,” Franklin said. “On hot days . . . if you get too many people in the pool, it uses up the chlorine pretty quickly.”

On the other hand, a pool that has had a poor track record isn’t necessarily unsafe now.

Low chlorine levels and cloudy pool water can be dangerous and have been linked with illness or accidental death.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the summer of 1988, 44 people contracted diarrhea after using a swimming pool at a school in Los Angeles County where a swimmer accidentally defecated in the water. The outbreak continued for several weeks until one of the pool’s three filters was fixed.

Some of the swimmers were diagnosed with cryptosporidiosis, a disease caused by a microscopic parasite that infects swimmers when they swallow water contaminated with infected fecal matter.

In 2004, the same parasite sickened more than 250 visitors and employees at a San Luis Obispo County water park. Parasite eggs were later found in the water slides’ filter. In a report published in 2006 in the journal Epidemiology and Infection, investigators said the water park’s operator failed to keep daily records of water quality and may have violated state requirements for clean pools and clear water in its wading pools. The report also said pool employees came to work even when they were sick.

In 2005, a report in the Orlando Sentinel said a 7-year-old boy’s body lay unnoticed at the bottom of a hotel pool in Florida for two hours. His body was obscured by murky water.

Cloudiness in a pool is usually triggered by debris -- urine, sweat, dirt, skin oil or laundry detergent -- that is introduced by swimmers, and there’s a point at which the amount of debris overtakes the amount of chlorine in the pool. The problem is exacerbated when pool water does not circulate properly through a filter.

Cloudiness is more common at older pools where the water circulates slowly through filters, and at smaller pools where a large number of people can contaminate the water more quickly.

All of the six pools visited by The Times last week were located at apartment buildings. Some managers and residents said the pools became dirty quickly during the first summer heat wave the weekend of June 21-22.

At an apartment complex in an unincorporated part of the county south of Whittier, a fog of green algae and a locked gate kept swimmers away from a pool at 8210 Broadway Ave. on June 24. The black stripe on the pool’s bottom was blurry. “That’s gross,” said Mike Perez, a resident. Manager Jaime Ramirez said he locked the pool June 21 after it became cloudy.

On June 25, at an apartment complex at Vanowen Street and Kelvin Avenue in Canoga Park, the pool in the courtyard was locked. Its bottom faded into a creamy soup.

Also on June 25, a county inspector tested a pool, which passed its last inspection two years ago, at the Nordhoff Townhomes in Panorama City.

On this day, the inspector said, tests showed almost no chlorine in the pool, where a lawn of green algae covered the bottom. In addition, he said, there was no chlorine in the adjacent hot tub, the drain cover at the bottom of the spa was cracked, and a metal railing leading to the pool and another leading to the spa were loose.

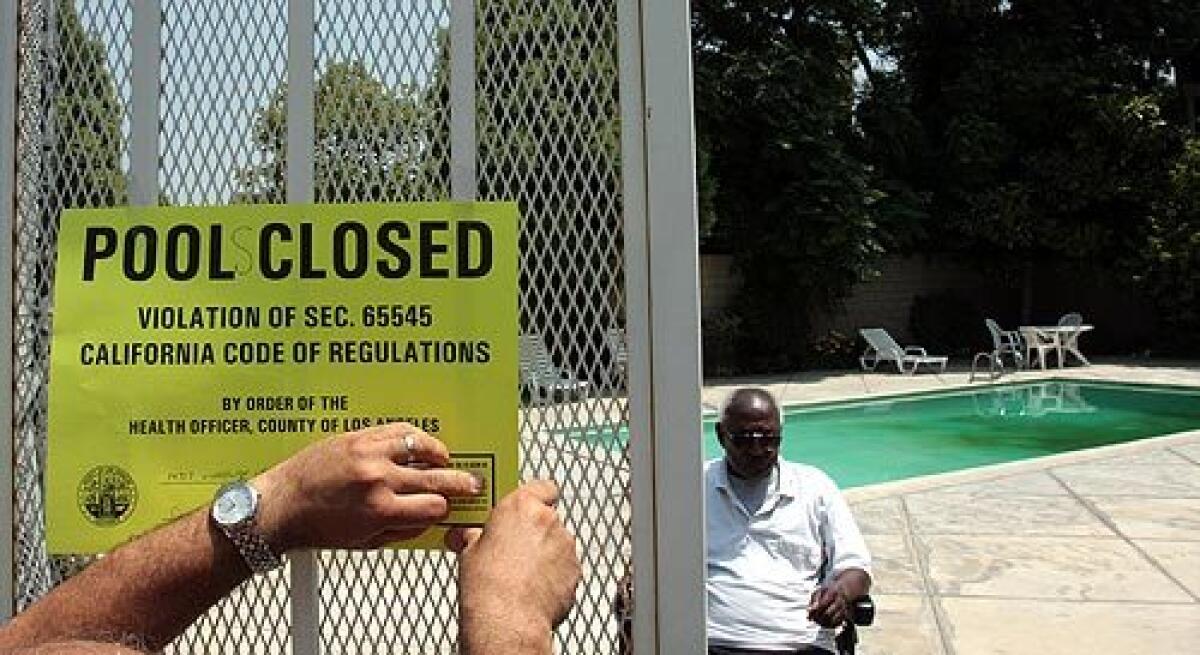

“This is an automatic closure,” inspector Sarkis Kharadjian said.

Manager Sylvester Norwood, 72, said the pool cleaner failed to remove the debris at the bottom of the pool. “He hasn’t been here in a week,” Norwood said.

Norwood also didn’t relish the prospect of extensive renovations.

“It’d be easier if they just fill it in.”

Those concerned about problems with pools in Los Angeles County can call inspectors at (626) 430-5360.

Times staff writers Charles Ornstein, Benjamin Reed and Francisco Vara-Orta contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.