Drought offers an opportunity to consider water policy

SACRAMENTO — So it’s official: We are in a serious drought. That means this: Next comes serious flooding.

But we’ll still be in a declared drought.

That’s just the nature of California weather patterns — and water politics.

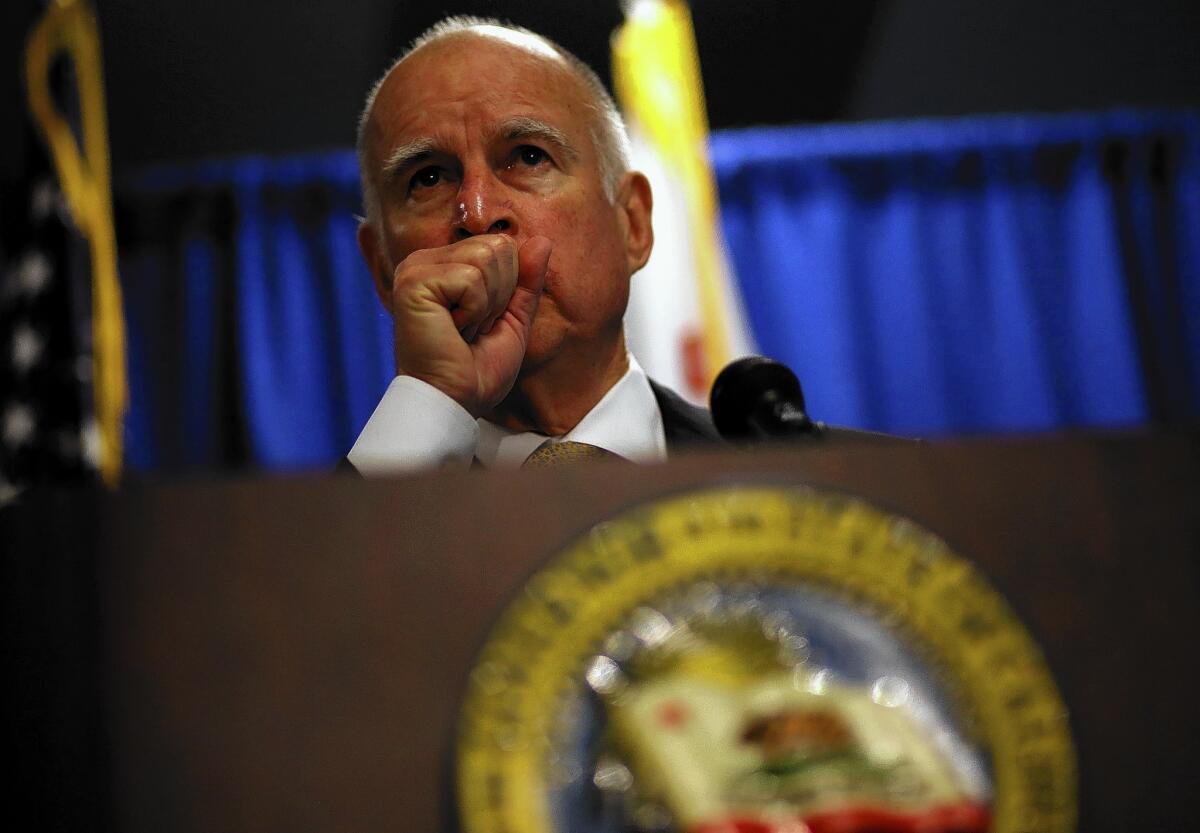

A drought proclamation, as issued by Gov. Jerry Brown on Friday, changes the political climate. It focuses public attention on the need for costly new waterworks.

Therefore governors and water officials are always reluctant to declare a drought over, even when rivers again leap their banks, fill reservoirs and send torrents of muddy snowmelt, uprooted trees and drowned livestock cascading into the Pacific.

That’s when we’ll curse ourselves for lack of foresight, for not having built the facilities to capture and store the floodwaters needed to get us through the next inevitable drought.

You can look it up: After virtually every severe drought there’s devastating flooding.

That doesn’t justify constructing just any waterworks. Brown’s hugely expensive ($25 billion), monstrous twin-tunnel project planned for California’s main water hole, the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, should be thoroughly reassessed.

The proposed 40-foot wide, 35-mile long tunnels would siphon off great volumes of Sacramento River water before it flows through the delta, robbing local farmers and fish and disfiguring one of California’s most bucolic areas. There hasn’t been enough serious thought to modernizing or relocating existing flawed facilities at the other end of the delta.

You also don’t hear much discussion of whether certain crops in California — wine and weed, for example — are justified in such quantities, given the great amounts of precious water they soak up.

Don’t we already have enough vineyards? And don’t tell me I can’t water my lawn when shady people in the hills are depleting the aquifers and poisoning the streams by growing pot. Then there’s fracking.

Water conservation shouldn’t be just for homeowners and renters — and hotel operators happy for any excuse not to provide clean towels.

But I’m meandering.

Brown’s declaration of a drought emergency is aimed at expediting water transfers, reservoir releases, conservation and federal relief.

But it also may inspire the Legislature to finally rewrite a pork-laden, $11.1-billion water bond proposal it passed in 2009 and twice yanked from the statewide ballot, certain that voters wouldn’t swallow it. The measure, it’s felt, needs to be pared by nearly half to be accepted by voters.

But who knows? This drought could soften voters’ attitudes about spending money for water. The key, I suspect, is not the size of the bond, but the content. Any new bond can’t include fatback like the old one did, such lard as bike trails, open-space purchases and “watershed education centers.”

Two legislators — Sen. Lois Wolk (D-Davis) and Assemblyman Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) — are pushing separate bond proposals, each priced at $6.5 billion. And both would require a tricky two-thirds legislative vote.

They would provide money for recycling, drinking-water treatment, storm-water management, groundwater cleanup, watershed protection and beefing up delta levees.

But there’s little mention of dam-building. Rendon’s proposal does include $1.5 billion for unspecified “storage.” That presumably could be above or below ground.

For my money, we need more reservoir space to store the inevitable flood waters. Some central and northern lakes are currently at only 40% to 60% of average water levels for this time of year. But we certainly could use a couple more of those pools.

The argument is about who’s going to pay for the multibillion-dollar dam construction. The water buffalos running irrigation and urban districts need to get over the notion that general taxpayers will foot up to half the cost.

Reservoirs should be mostly paid for by water users through higher rates. The state general fund — fed by all taxpayers—could kick in, say, 10%. And that should be included in any bond proposal.

Ironically, Brown’s drought declaration will provide momentum for a November water bond measure that he sought to avoid while seeking reelection. The governor privately tells people he desires an “uncluttered” ballot — and specifically doesn’t want it to include a water bond.

Many Capitol players theorize he merely doesn’t want a water bond proposition to become a referendum on his controversial twin-tunnel scheme. And it very well could.

But Rendon thinks the time is ripe for a bond.

“The lack of snowpack and rainfall may whet the public appetite for a water bond,” he says, adding: “It’s almost impossible to talk about water without using puns.”

Senate leader Darrell Steinberg (D-Sacramento) will propose legislation to tap into bond money previously approved but unused. There’s about $1 billion available, he says, and thinks lawmakers should be able to spend at least half for various recycling, storm water, groundwater and conservation projects.

“Water is on the minds of people for a good reason,” Steinberg says. “These conditions create a window of opportunity we don’t want to miss.”

Brown, in his proposed state budget, also included $619 million for a “water action plan” to improve efficiency and conservation.

In making the drought official, the governor noted that the last calendar year was California’s driest on record. “We’re in an unprecedented, very serious situation,” he said.

“We can’t make it rain, but we can be much better prepared for the terrible consequences that drought now threatens.”

And for the future opportunities to flow from flooding.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.