Iraq veterans find the war is at home with red tape

SAN FRANCISCO — Glenda Flowers stood at the edge of a crowd of angry veterans at San Francisco’s War Memorial building. They had been waiting months, even years, to hear whether they would receive disability benefits, and they were tired of excuses.

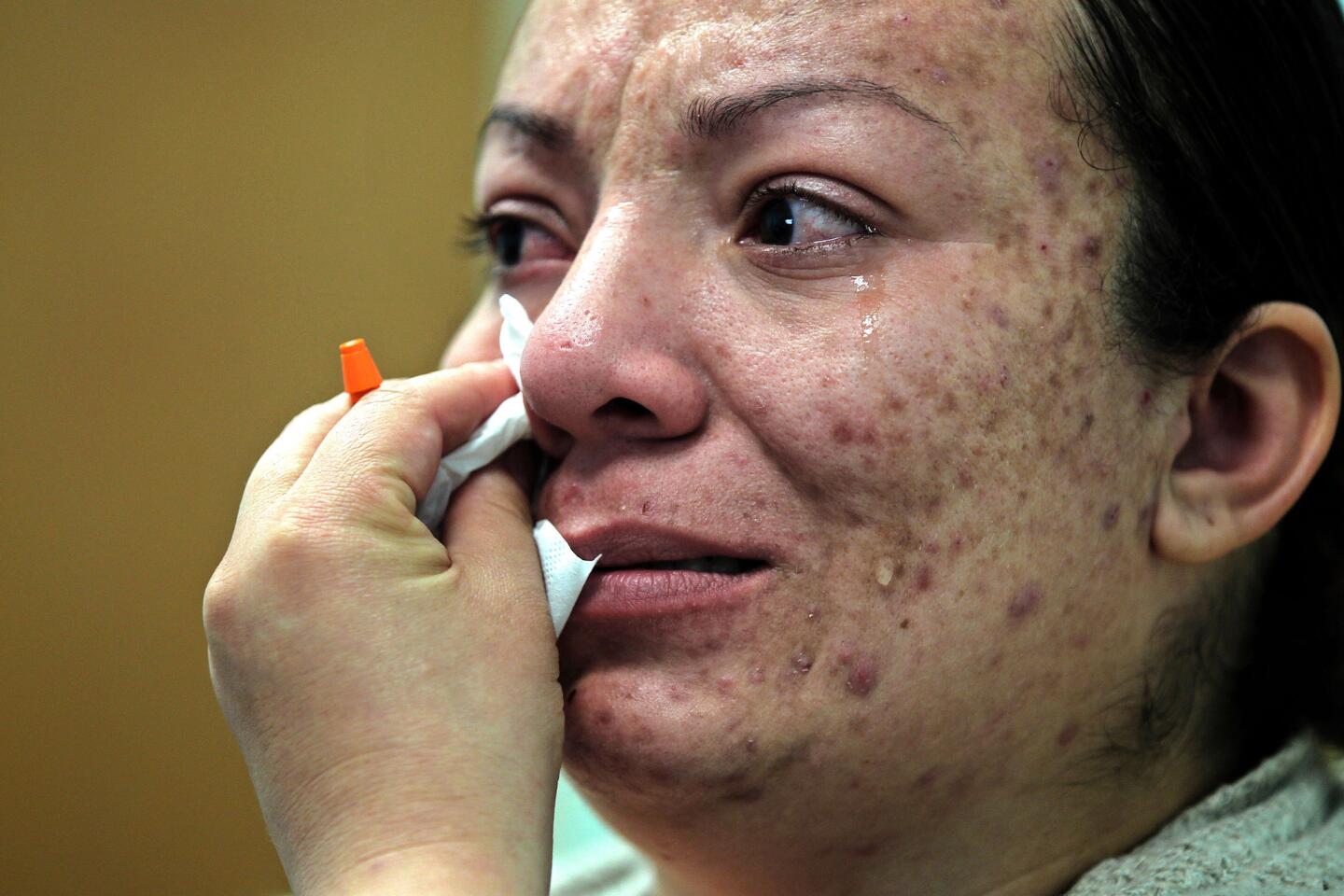

Flowers, a 31-year-old Iraq veteran and mother of two, had come to the meeting with a pair of Veterans Affairs officials because she wanted to be heard. But she was trying too hard to fight back tears to take the microphone.

The social worker who accompanied her couldn’t let her be overlooked.

“Nobody brought up here that a lot of these young vets have children,” said Marcy Orosco, who heads a Salvation Army transitional housing program in San Francisco. “Because of this wait, she was living in her car with her children.… What are you going to do about that?”

Flowers, a small, compact woman eager for adventure, thought the Army would be her life. But when her marriage to a fellow soldier and her mental health collapsed under the strain of their tours to Iraq, she found herself alone with her children facing the prospect of another deployment.

She left the Army in January 2010 and submitted a benefits claim the same month, citing post-traumatic stress disorder and injuries from years of parachute jumps, among other ailments.

She didn’t know it at the time, but her application would become a case study in the kinds of issues that can delay a claim.

Another Iraq veteran, Ari Sonnenberg, said the agonizing wait and bureaucratic bungling added to an already painful transition to civilian life. He wonders how many people will want to serve in the future.

“I never used to understand why the Vietnam guys were so bitter,” he said. “We’re very quick to send people to war, but we’re super slow taking care of those people that actually make that sacrifice.”

::

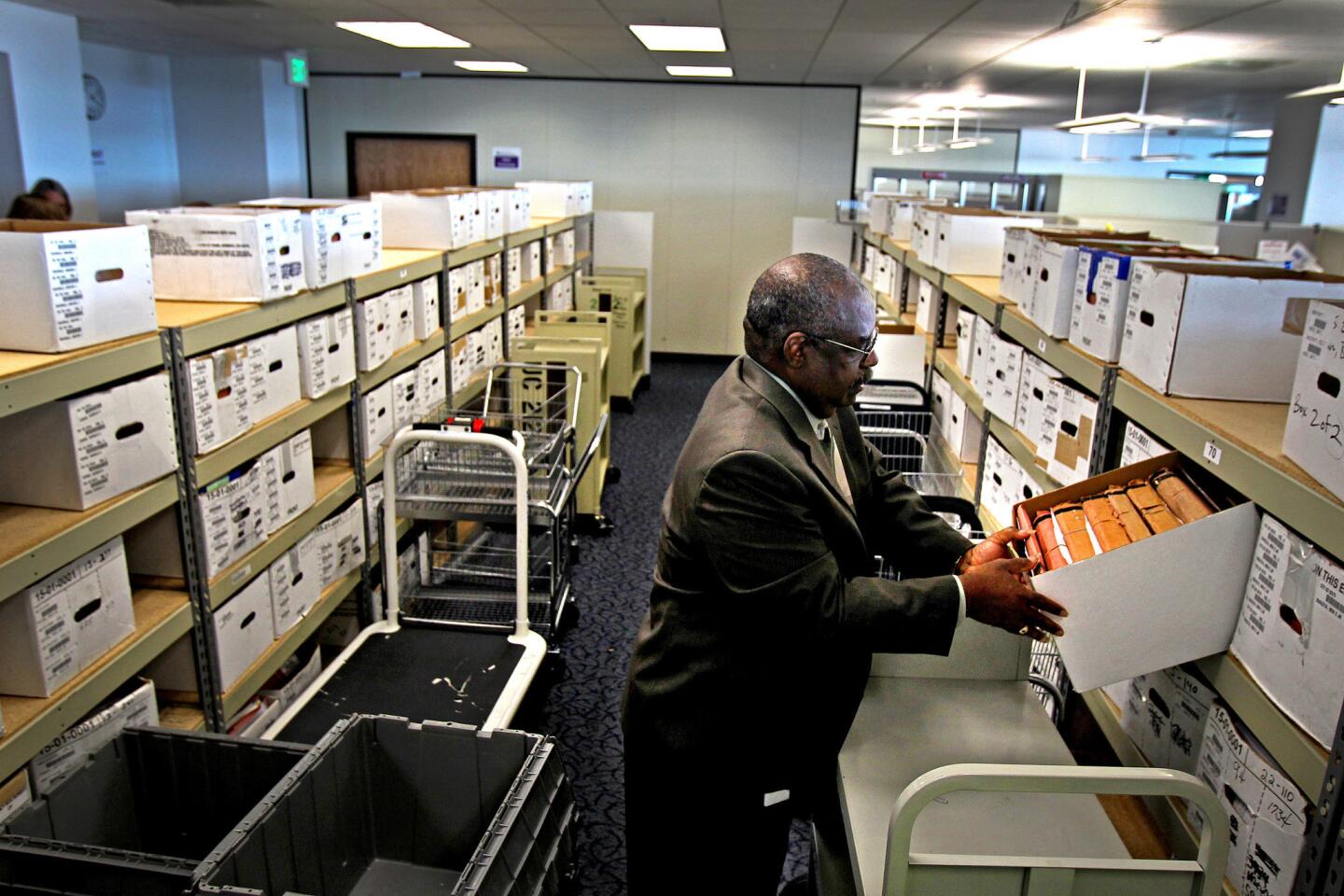

Willie Clark, the western-area director for the VA’s Veterans Benefits Administration, made a promise that April day in San Francisco:

“We’re going to start with our oldest cases, cases in excess of two years, we’re going to complete every one of them and we’re going to do so within the next 60 days.

“And once we fix those,” he said, “we’ll start with our 1-year-old cases.... We owe it to you to get this done.”

In the months since the meeting, the VA has made progress, reducing the number of claims pending more than 125 days by 35%, from a peak of 611,000 in March.

A new computer system is helping to speed up claims processing, which until this year was still mostly handled on paper — about 5,000 tons of it a year, officials said. Additional staff has been hired, training has been revamped and the work flow has been reorganized.

The partial government shutdown in October was a temporary setback, forcing the department to suspend mandatory overtime for claims processors. When the department resumed full operations, officials said, they couldn’t keep their promise to clear out all cases that had been pending more than a year by the end of the month.

But as of Nov. 4, 94% of these claims had been processed, according to VA figures. By 2015, officials are promising to process all claims within 125 days.

Although a growing number of veterans are now receiving aid, they say the damage done to their financial stability, family relationships and own self-worth is not so easily remedied.

::

Sonnenberg, a pale, wiry bundle of nerves who deployed three times to Iraq, didn’t attend the San Francisco meeting. He took part in a similar forum last year and couldn’t face another round. He sent some of his artwork to be displayed in his place.

The sad “naïve” figures, painted against dark, swirling backgrounds, are one of the ways he tries to deal with searing memories from Iraq. One dreadful day stands out, the day that multiple bombers struck a village near the combat outpost where he was serving as a platoon sergeant. Ambulances packed with scores of wounded arrived at the gates.

Sonnenberg, 37, is haunted by all the blood, the screams and the lives lost — many of them children. When helicopters had evacuated the last of the survivors, he says, he sent his soldiers to bed while he scrubbed the blood away.

“I did it so my guys wouldn’t have to do it,” he said. “So they wouldn’t have to wake up to that.”

Long after he left the Army in 2009, his wife, Patty, would find him scrubbing, convinced there was blood everywhere. He couldn’t stand to be near his son, who reminded him of the children in Iraq. Crowds made him shaky and short of breath. He barely slept, suffered frequent memory lapses and would burst into a rage at the slightest provocation. When his wife was recovering from cancer, she had to work because he couldn’t function in a job.

For a time, he sought solace and purpose by working as a priest at Hare Krishna temples in India and Africa. But he said, “I was an angry monk and apparently you can’t be that.”

Although Sonnenberg is at pains to point out the excellent care he has received from VA hospitals for PTSD and a traumatic brain injury, he said dealing with the benefits section was a constant runaround.

“You’d call up and you’d ask, ‘What’s the status?’ Nobody knew,” he said. “Then you’d make an official inquiry, and they would say, ‘OK, here’s the number.’ And then when you call up a week later, there’s no record of that inquiry.”

In an attempt to expedite his claim, the VA office in Oakland sent the file to be processed in another state. But documents were apparently misplaced in the transfer. Sonnenberg says he was asked to resubmit paperwork, in some cases multiple times.

“I was losing my mind at one point,” he said. “I just started to feel like it was hopeless.… Nothing’s going to change, no one gives a damn about us.”

One day, he walked into the woods near his former home in Belgium, intent on killing himself. His wife found him with a knife to his throat. It wasn’t the only time she would have to talk him out of attempting suicide.

It took a year to get an initial rating of 80% disabled. By the time of the town hall meeting, Sonnenberg had a 100% rating and was receiving a little more than $3,500 a month.

With the money he now receives, he has rented a cottage in Mountain View, within bicycling distance of two VA hospitals. He attends therapy sessions most days and says he’s making progress — but too late, he fears, to save his marriage.

Late last year, Patty filed for a legal separation. They are trying to resolve their differences, but Sonnenberg doesn’t allow himself much hope: “The disappointment is too great.”

::

Every time Flowers called for an update about her claim, there seemed to be a new issue.

She says that the Defense Department couldn’t locate some of her medical records, so she provided the VA with letters from her supervisors attesting to her injuries and a copy of her jump log. But she says that when she called to verify the faxes were received, she was told there were no such documents on file.

Medical exams had to be scheduled to evaluate each of the more than a dozen medical issues she listed. When she asked to reschedule some exams because her son had fallen ill, it took two months to get new appointments. Benefits officials say they put in the requests a week after she called, but the hospital canceled them, citing insufficient information — probably because her file had not been sent over.

Because Flowers’ claim was processed on paper, her entire file had to go to the hospital for each exam. In one instance, it took more than two months to get it back, benefits officials say. In another, the claims processor had trouble interpreting the doctor’s report and the file had to go back for clarification.

After waiting nearly a year, Flowers was rated 50% disabled in December 2010, which qualified her to receive $969 a month. But she says her issues were more numerous and severe than the VA recognized, so she went back for more help.

She tried an office job, but was asked to leave after a week because of her yelling. The PTSD makes her edgy and defensive, says Flowers, who acknowledges that she went AWOL near the end of her service. Although she receives free treatment from the VA, she was missing appointments because she didn’t have the money for child care and car repairs.

By the spring of 2012, she was falling behind on rent. Flowers pleaded with the VA to expedite her claim and was provided with a partial decision that increased her compensation to $1,537. But she was told that her mental health issues and a brain injury required further evaluation.

In April, a sheriff’s deputy showed up at her door with an eviction notice. Flowers borrowed a car from a friend and told the children, Demond, 7, and Tatyana, 4, that they were going on a road trip. They toured the sites of San Francisco: Ocean Beach, Fisherman’s Wharf and Union Square. At night, the children curled up on the back seat, while Flowers kept an anxious vigil.

“I was too scared to sleep,” she said.

They lived out of the car for a week, until a Marin County social worker found the family a room at Orosco’s facility, Harbor House.

VA officials acknowledge that “the ball was dropped” and there were problems with the way both cases were handled. “That’s why we’re undertaking these steps to get these old cases done,” Clark said.

He says the new computer system will remedy many of the difficulties encountered by Flowers and Sonnenberg. When veterans submit their paperwork electronically, it is instantly accessible to anyone working on the case, eliminating delays and reducing the likelihood that documents will vanish.

“I have a great deal of empathy for our veterans who are facing severe financial hardship,” Allison Hickey, the VA’s undersecretary for benefits, told The Times. “They have to let us know they are in those circumstances.... We prioritize that.”

Not long after the town hall meeting, Flowers was rated 100% disabled, which qualified her to receive $3,502 a month. The VA is also helping her apply for housing assistance and providing vocational training. But she says that she is still paying off debts.

She tries to put on a brave face for the children, but wonders who will rent the family an apartment with her bad credit rating.

“It’s frustrating and depressing because I want stability for my kids, and I really can’t provide that,” she said, tears welling in her eyes as the children romped in a Harbor House playroom.

Demond crawled into her lap.

“Stop crying,” the boy said gently. His mother reached for a Kleenex and gave Demond a squeeze.

“I’m trying,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.