Gay sports leagues gain ground against bars as a social outlet

Gay bars once were a main meeting place for those seeking same-sex friendships. But the rise of social media has helped make gay sports leagues a popular alternative.

Jason Bergquist tugs the laces tight on his Nike cleats and grins at his parents in the front row of the bleachers at the Hollywood Recreation Center. With zero wins for the season, Bergquist's kickball team has a lot to prove.

His mother snaps iPhone photos of him in his yellow team T-shirt.

"J, you need your water?" she asks through the dugout's chain-link fence.

"Not yet, Mom."

His father can't stop smiling. "This reminds me of when the kids were little!" he says before trying to persuade other fans to do the wave.

Bergquist, 34, is playing for the Racine team of the Varsity Gay League, one of Southern California's largest recreational sports organizations specifically for gay people.

He joined the league this year, still reeling from a breakup with a longtime boyfriend. Frustrated and lonely, he promised himself he'd put himself out there and meet new people.

"My parents had been softly encouraging me to begin making new friends and start dating again," said Bergquist, whose parents are visiting from Seattle. "And they've been worried about me meeting people at bars."

He was looking for more genuine friendships anyway, he said. At a bar, he said, people — gay or straight — are trying to impress. In competitive team sports, they have to rely on one another.

For Bergquist, who played soccer in college, the Varsity Gay League offered a perfect opportunity and a "healing experience."

"We're not out there celebrating being gay; we're not waving flags," he said. "It's to have a good time and build new relationships and friendships."

Members of the Racine team huddle at the end of a kickball game at the Hollywood Recreation Center.

One Saturday night a few years ago, league founder Will Hackner and a few friends were doing the same thing they did every Saturday night: grabbing two-for-one margaritas at a West Hollywood bar, staring at other people and not talking to anyone because the music was too loud.

They left the bar and walked to a nearby park. A friend nudged him and yelled, "You're it!" Quickly, strangers joined in their game of tag, laughing as they ran through the park.

Hackner was inspired. He emailed gay friends and acquaintances, inviting them to play a game of Capture the Flag in Pan Pacific Park. To his surprise, more than 50 people showed up that Sunday morning in 2007.

It was the first event in what would become the Varsity Gay League. Today, the league includes bowling, tennis, volleyball, poker, even Quidditch. On a recent Sunday, Jason Collins, the NBA's first openly gay active player, joined a league kickball match at the Hollywood center, with teammates yelling, "Good job!" as he rounded the bases.

Gay bars remain a popular social gathering place, but a new generation of sports leagues is offering an alternative to a late-night lifestyle that some find unhealthy or unappealing.

The leagues, which are popular in Chicago, New York City, San Francisco, Boston and numerous other cities, are part of what many see as a generational shift in the gay community.

For decades, bars were the best option most gay men and lesbians had to meet each other and "took the role of a social club," said historian Lillian Faderman, author of the book "Gay L.A."

Hackner, 33, who now runs the league full time, says he often gets emails from people saying they're recently sober and that the league is a godsend.

With more than 1,000 people on its rosters, the league has been so successful that Hackner is regularly asked if straight people can join the fun. Of course they can, he says, and they do.

You meet people to date, people to be friends with, people who can give you job opportunities."

Bergquist's team, Racine, and its rival on this afternoon, the Marla Hooches, both picked names inspired by the 1992 movie "A League of Their Own" about the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, whose players stepped up to the plate when World War II threatened to end professional baseball — to jeers from people who didn't think they could play ball.

Racine's season started with a game in which the team lost 13 to 0, and it continued losing. But the players are hopeful. A teammate shrugs off the losses before jogging into the dugout, saying, "We're winners at heart!"

Bergquist's team is on offense first. Someone plugs an iPod into a speaker, and swing songs from "A League of Their Own" swell over the crowd. Bergquist's parents cheer.

Bergquist's rivals sport white T-shirts emblazoned with the name Hooch — after the movie's Marla Hooch, a homely woman who's a talented batter.

The Hooches' pitcher, Ross Von Metzke, takes the mound in knee-high red socks and sunglasses. He's got fans in the audience, and he knows it, waving and smiling before tossing the red rubber kickball across the plate.

To Bergquist's delight, Racine scores first. But by the end of the first inning, his team is losing.

In the top of the fourth inning, with two on base, a Racine kicker sends the ball over the left field fence, but Racine still trails the Hooches 6 to 4.

The bases are loaded and Racine has two outs when Bergquist next goes to the plate. He rubs his hands together, nervous.

He kicks the ball to left field — but it is too high and caught by an outfielder. He's out and the inning is over.

"You did good, son," his dad says.

Like the Varsity Gay League, other gay sports leagues have assumed the dual role of competitive sports organization and positive social outlet.

One of the country's largest, the Chicago Metropolitan Sports Assn. — with about 4,000 members — "is really about social networking and mentoring," said Michael Erwin, a board member.

"Being gay or lesbian, there aren't a lot of gay role models in your life," Erwin said. In the league, there are people at all stages of coming out of the closet, and "You meet people to date, people to be friends with, people who can give you job opportunities." Erwin met his partner of three years on a league football team.

The Lambda Basketball league in Los Angeles is "about creating more-than-basketball moments," said Jason Jamarillo, its president.

Lambda Basketball uses its platform to promote other healthy lifestyle choices, such as safe sex, Jamarillo said. It recently partnered with an initiative to hand out a million free condoms, its athletes photographed for promotions.

Opposing pitcher Scott Foy, left, waits for the kick by a member of the Racine team.

The leagues are not anti-alcohol — they often have after-game drinks at local bars.

But the ability to meet other gay people outside bars has boomed in recent years with the advent of social media and a more accepting society, said Mark Rosenberg, 30, a gay author who has written about his own struggles with alcoholism.

"When I was younger, it was just ingrained in me that bars and clubs were the places to go to meet people," he said. "But it's just not the truth anymore."

By the final inning of the kickball game, Racine trails the Hooches 8 to 4.

Racine's captain kicks the ball to left field and quickly scores. Bergquist's father finally gets the wave going among the two dozen or so in the stands. Two more runners score, and Racine brings the score to within one point: 8 to 7.

By the time Bergquist makes it up to kick, the bases are loaded. There are two outs. He has not scored in this game, and he is nervous.

Bergquist's dad laces his fingers through the chain-link fence, jumping up and down. Bergquist kicks the ball hard. It flies past the third baseman, just far and fast enough for two runners to score.

The score is 9 to 8. Racine wins.

Bergquist's teammates — his new friends — huddle around him in celebration and pose for team pictures. His father is so proud, he jumps into the photo.

Follow Hailey Branson-Potts (@haileybranson) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

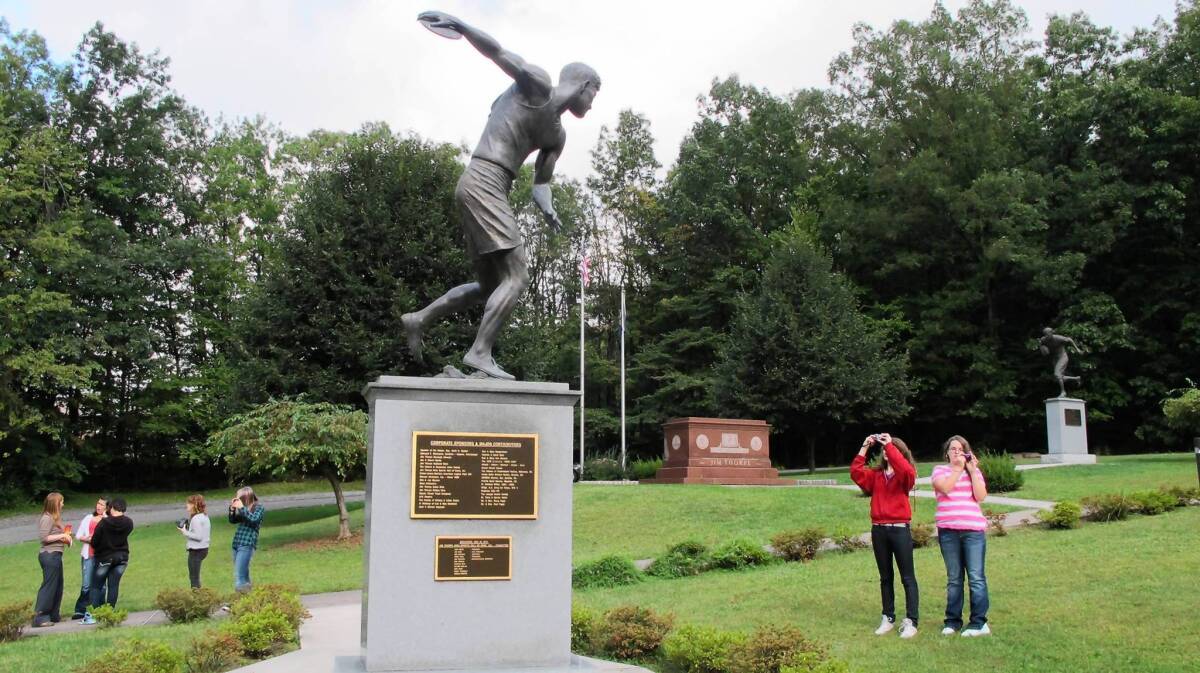

Jim Thorpe, Pa., fights to keep its namesake

We are all set to bury Dad in Oklahoma and then — boom! — he was gone, never to be returned."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.