Bridge design sparks clash in Los Angeles

- Share via

The bridges that span the Los Angeles River offer a history lesson of how Los Angeles became a modern city.

There’s the Cesar Chavez Bridge, with its colossal porticoes, embellished with spiral columns and a replica of the city seal. The bridge, decorated with elements of the Spanish Baroque style, is an architectural nod to the historic El Camino Real, of which it is a part, and to the city’s Spanish heritage.

The beaux-arts North Broadway Bridge, originally named the Buena Vista Viaduct, is one of the river’s older structures and was the state’s longest and widest concrete arch bridge when it opened in 1911.

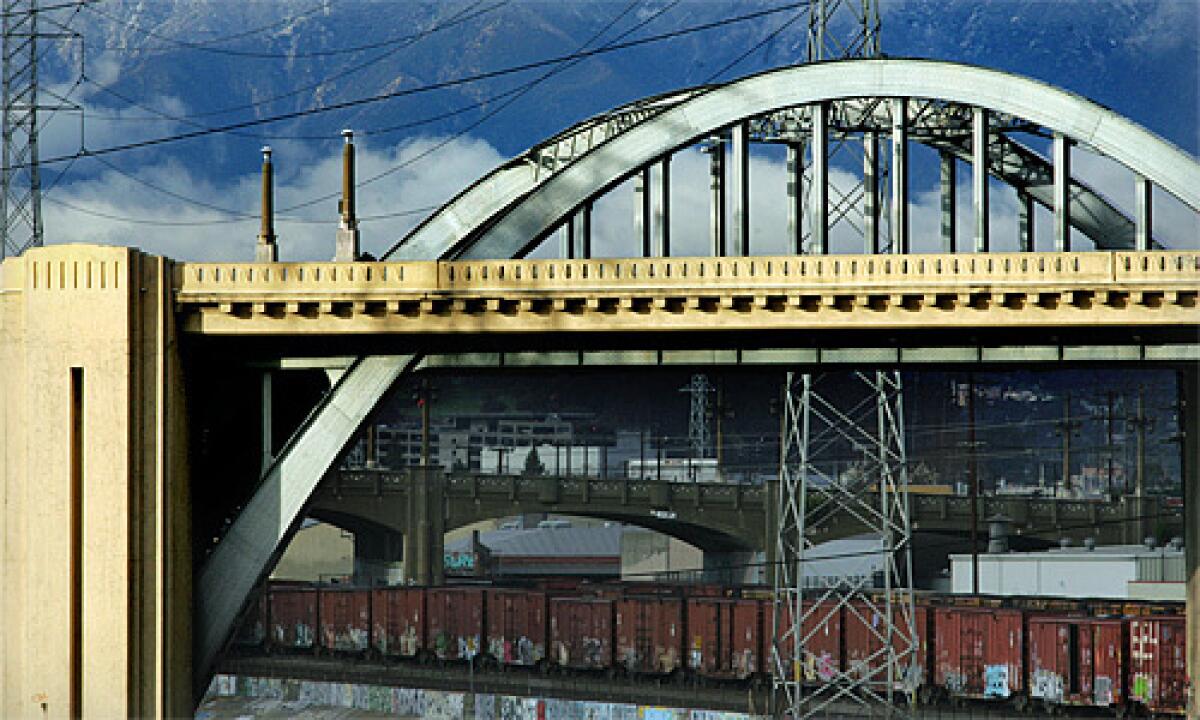

Then there is the 6th Street Viaduct, a streamline-moderne monolith of steel arches and concrete towers built in 1932.

The city wants to replace the span with a spare, modern cable-stayed bridge. Officials released new design plans for the bridge in recent days that were met with criticism from those who say that the modern look has no place amid the ornate spans.

“I said as far as I am concerned, if you are going to put this bridge with cables there, you might as well not put a bridge there at all. I would rather not see one there,” said Victoria Torres, a board member of the Boyle Heights Historical Society. “It’s very disappointing when the city is trying to push something on you that you didn’t agree with.”

At two-thirds of a mile long, the Sixth Street Viaduct is the largest and longest span across the Los Angeles River. Known for its two sweeping steel arches and a rather notable curve in the middle, the viaduct is punctuated at either end by decorative pylons with fluted, zigzag designs. Railroad tracks run underneath on both banks of the river.

When the viaduct was built, masons used concrete from a plant that had been constructed on site at the river’s edge for the building of the bridge. The practice was revolutionary at the time -- but an aggregate used in the making of the concrete caused it to have a high alkali content. As water has seeped into the concrete over time, the concrete has begun to erode. The rare degenerative condition is called alkali-silica reaction, and officials say it has weakened the viaduct to the point that officials say it has a 70% chance of collapsing in a major earthquake within 50 years. It is the only span along the river to have such a condition.

“It is an irreversible chemical erosion,” said Department of Public Works spokeswoman Tonya Durrell. “We describe it as a pretty sick bridge, like a cancer.”

City officials have been debating what to do about the bridge for several years, weighing three options: retrofitting it, replacing it or doing nothing. The latter made little sense, they said, because of the severity of the erosion.

After a series of public meetings over the last two years, city engineers decided that replacing the bridge was the only viable option, because retrofitting would yield a life cycle of only about 30 years. Outside of exact replication, they considered four possible designs, said Durrell, two that were modern and two that included more historical features, before recommending the cable-stayed bridge.

“Once you take down a monumental structure like the 6th Street Bridge, it was our opinion that we ought to build something state-of-the-art as opposed to a replica,” said DPW engineer John Koo. A replica, he said, would cost an extra $30 million.

Philip Richardson, program manager of the DPW’s bridge improvement program, said officials worry that delays over the design could result in a loss of state funding.

At the meeting where the new design was unveiled, City Engineer Gary Moore said he thought the replacement should have a “wow factor.”

A model of the proposed span shows two rectangular towers in the middle of the bridge, with cables down both sides.

City officials said the tight curve on the current bridge would be straightened, and the bridge would run from one bank to the other with a much more gentle curve.

But critics said the design was a direct affront to the direction that advisory committee members had suggested to the city.

Torres, who has been a member of the 6th Street Viaduct community advisory committee, said she and others had voiced overwhelming support for an option that recreated the bridge exactly as it is now, with modern construction.

Los Angeles City Councilman Jose Huizar, who represents the communities on both sides of the viaduct, said he favored keeping some of the historical aspects of the original bridge -- though he said he was waiting to hear community reaction about the design.

“We have very few iconic structures to begin with, but if you look at these bridges, they represent Los Angeles,” he said.

Huizar used to have a paper route and would ride his bike along the 6th Street Bridge from Boyle Heights to pick up Japanese newspapers in Little Tokyo.

“I would ride my bike over the bridge beginning in the fifth grade all the way to the ninth grade, and I’d pick up the newspapers and go distribute them in Boyle Heights,” he said. “I know these bridges well.”

Mike Buhler, director of advocacy for the Los Angeles Conservancy, said his organization had not yet conceded that the viaduct necessarily needed to be replaced -- though he quickly added that the organization would never advocate for an alternative that would jeopardize public safety. The organization has not yet taken a stand on the new design.

The cost of replacing the viaduct with the proposed structure is estimated to be about $345 million, officials said.

The bridges are throwbacks to a time in Los Angeles before sprawl, when linking the city center on the west side of the Los Angeles River and the bustling neighborhoods on the east side was of key importance.

The spans have become treasured historic structures and celebrated in scores of movies, including “Grease,” “Devil in a Blue Dress” and “Terminator 2.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.