Great Read: Honduran parents, daughters are a family at last — for now

When Silvia Padilla was pregnant with her second daughter, she and her husband, Marvin Varela, hatched a plan that broke their hearts: They would go to America and leave their girls behind.

Marvin left Honduras with a smuggler one night in 2004. Silvia joined him in Los Angeles three years later and immediately wanted to go back. “She didn’t think she could endure life without them,” Marvin said. “But time passed and she adapted.”

For seven years they lived with other immigrants in small apartments near MacArthur Park. Using fake identification papers she bought on Alvarado Street, Silvia found a job at a factory. Marvin worked for the building contractor who had paid his way to the United States. At the end of every month, they wired money to Honduras.

In Internet video chats, they watched as their daughters lost their baby teeth and grew taller. “Come home,” the girls sometimes begged.

Their parents told them that one day, when they had earned enough, they would return to Tegucigalpa, open a store and build a house.

And then, in nervous phone calls, friends and relatives in Honduras started telling them the gang that had long roamed the dirt streets of their slum was getting bolder. Several of Marvin’s childhood friends were killed for refusing to join. His mother and brothers were threatened. One day while Katheryn, their elder daughter, was at a soccer match, assassins armed with automatic weapons walked up to a spectator and shot him to death.

So Marvin and Silvia forged a new plan. In October, they wired $8,000 to a stranger to smuggle their daughters north.

::

For six days, the parents waited and worried. Then Silvia got a call from a Border Patrol agent. Their daughters had been caught while trying to cross the Rio Grande near McAllen, Texas.

The girls were flown to a temporary children’s shelter in Oregon. Government prosecutors would file deportation paperwork, but while the girls waited for their cases to be heard in court, they would be released into the custody of their parents.

Silvia drove all day and night to reach them. When she finally gathered them in her arms, she sobbed.

Katheryn, 13, and her sister, Dayana, 9, are among more than 60,000 unaccompanied children, mostly from Central America, who have been apprehended at the border over the last 10 months. The surge, which has overwhelmed federal authorities and reignited the immigration debate, seems to have leveled off for now. But its effects are just beginning to be felt in cities across the country.

Around 85% of the young immigrants have been released into the care of relatives, according to federal statistics, with nearly 4,000 turned over to guardians in California during the first seven months of this year. Los Angeles, home to some of the nation’s largest communities of immigrants from El Salvador and Honduras, has been the destination for many.

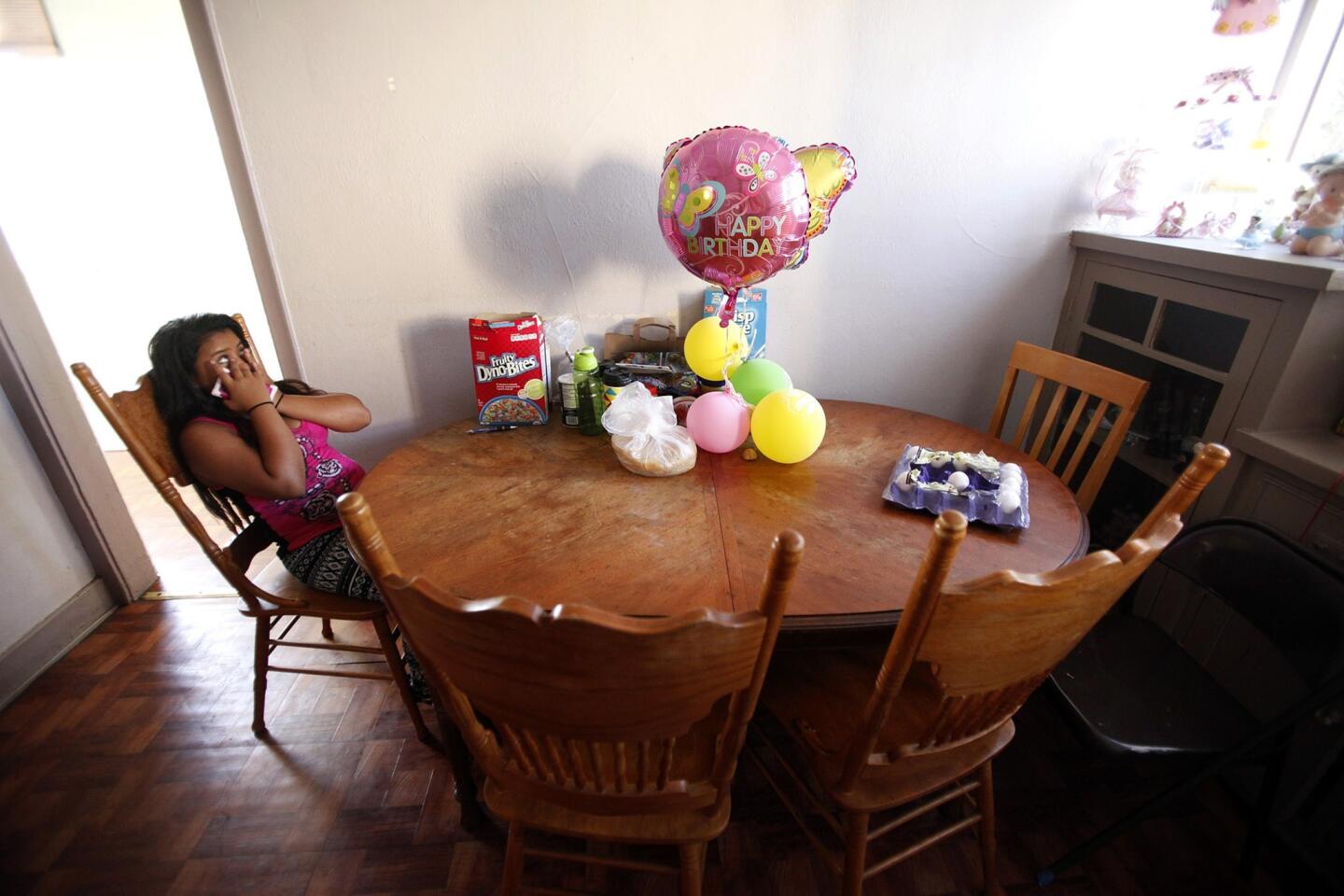

When the girls arrived in L.A., Silvia and Marvin’s friends held a party to celebrate the reunion. Beer was chilled and carne asada grilled. Marvin, on a rare break from work, lifted the girls into the air again and again.

It had been a decade since he had seen Katheryn. It was the first time he had ever held Dayana.

They spent their first days together taking in the city sights. On Facebook, Marvin proudly posted photos of outings to the Santa Monica Pier and the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Silvia enrolled the girls in school. In the evenings, all four of them slept in one bed; Katheryn and Dayana didn’t want to be separated from their parents, not even for a single night.

But quickly it became clear that living together as a family was an acquired skill, and they were out of practice.

::

On a hot Saturday afternoon, Silvia and her girls walk down Olympic Boulevard past strip mall churches and liquor stores that advertise in both Spanish and Korean. Dayana holds her mother’s hand. Katheryn, a few steps behind them, types on her smartphone, rarely looking up.

In the bright aisles of the supermarket, Dayana runs the show.

She places a bag of ice pops and a box of ice cream sandwiches into the cart Silvia is pushing, and then a carton of Dryer’s. In the checkout line, she holds up a Snickers bar. “Mama?” she pleads. Silvia gives a quick, compliant nod.

In Tegucigalpa, the girls were spoiled by their grandparents — especially Dayana, whose big brown eyes and warm manner can be hard to deny. Now her anger flares when her mom refuses her treats. Katheryn, naturally quieter and more distant, has entered the eye-rolling phase of adolescence. She bristles at Silvia’s demands that she go to sleep at 8:30 p.m. and that she and Dayana stay inside to play.

In the early months, Silvia felt overwhelmed. Her daughters both look like her — short, with glossy black hair and round cheeks — but sometimes it seemed like they were strangers.

“It was like starting over,” Silvia said. “Like getting to know each other for the first time.”

Several months ago, Silvia went to Katheryn’s school and asked for parenting advice. She was connected with a group that provides free counseling, and now the family meets with a therapist once a week. They talk about what distance does to relationships, and how to work through disagreements.

“It’s a process, little by little,” Marvin said. “We’re adapting to each other, and trying to understand each other.”

He knows firsthand the strain of having a parent far from home.

Even when he was growing up in the 1980s, lots of children had one or two parents in the United States. He was just a boy when his father left to find work as a house painter in Georgia. His dad took to American life and the family never heard from him again.

Marvin dropped out in middle school to help his mother, who sold tortillas on streets lined with concrete shacks. At 18, he married Silvia, a popular girl from his block. She had also quit school to help support her family.

Their decision to come to the United States wasn’t easy. Marvin didn’t want to be absent, like his father. But he and Silvia were determined to give their daughters more opportunities than they had. They wanted the girls to grow up to become doctors or dentists.

Now they worried: What if the girls were sent home?

::

The couple spent months looking for lawyers for the girls, but most attorneys charged thousands of dollars just to take on a new case.

This summer, shortly before Dayana’s first deportation hearing in a case that will take many months to be decided, they discovered a pro bono law firm called El Rescate that paired them with a lawyer for only a small fee.

The attorney, Alex Holguin, said their best shot was filing for asylum. During a meeting at the organization’s threadbare office in a small brick building on West 8th Street, he asked Katheryn and Dayana to write about the gang violence they had seen in Honduras, and the threats against their family.

But he also leveled with them. “The vast majority of these cases are denied, to be honest with you,” he said.

Silvia can’t conceive of the possibility of them being sent home.

One morning last month, she and Dayana boarded an elevator in an unassuming office building near Pershing Square. They passed through a metal detector and walked into a small courtroom.

It was Silvia’s first time in court. Even though Dayana’s attorney had assured her that her own immigration status wouldn’t be questioned if she attended the court proceeding, Silvia was nervous, twisting her fingers in her lap.

Most of the cases on the docket involved adults. Dayana, the only child in the courtroom, wore a bright blue T-shirt emblazoned with the word “Love” in glitter. She rested her head on her mother’s shoulder. Silvia brushed a few specks of glitter from her chubby cheeks. When Silvia tried to edge a speck of dirt out from underneath Dayana’s nail, the little girl squirmed.

The judge called Dayana’s name, and she and Silvia approached the bench shyly. “I see that your client is accompanied by an adult,” the judge asked their attorney. “Who is that?”

He answered quickly: “Her mother.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.