Great Read: Dreaming of a happy ending: Bedtime stories capture the longing of deported parents and their children

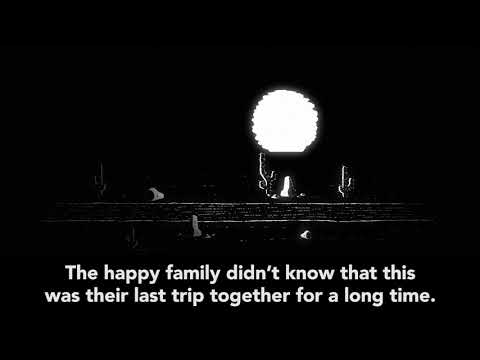

Reporting from TIJUANA — The nighttime ritual has always been the same for Emma Sanchez Paulsen and her three sons: They pile onto her bed as she begins to weave a tale.

The bedtime stories in their home in Vista, Calif., used to be about her childhood in Mexico — running through green pastures or strolling through city plazas. Then, nine years ago, when Alex was 5, Ryan was 3 and Brannon was just 2 months old, she was banished from the United States. The only time they could cuddle on her bed was when they visited her in Tijuana.

Instead of telling stories about Mexico, Sanchez Paulsen found herself fielding questions from three children who didn’t understand why a border stood between their mother and father.

And the boys became the ones creating stories.

What Emma Sanchez Paulsen misses most about her three American sons is reading to them at bedtime. Nine years ago, Emma was deported from the U.S. for entering illegally. This is her favorite bedtime story. (Lisa Biagiotti/Los Angeles Times)

They devised a series of childish schemes to get their mother back to the U.S. One involved a trampoline to bounce over the border wall. Or maybe they could attach a bunch of balloons to her limbs. Or put her in a box.

One time, when Brannon was about 3, he asked if it would be OK to turn her into little pieces of paper.

“This way I can take you with me across the line,” he said. “And then I can put you together with glue when we get back home.”

On the many nights she spent alone, Sanchez Paulsen wrote what she describes as the most important bedtime story she’ll ever tell: a fantastical tale about a young elf who joins with his brothers to battle dragons as they visit their mother in the land of the fairies.

That narrative, “The Little Elf,” is now part of a collection of bedtime stories written by mothers and fathers living in Tijuana who have been separated from their families, for a book project called “Cuentos Para Dormir,” or “Bedtime Stories.”

For nearly a year, educator and activist Sophia Sobko has crossed the border to Tijuana almost weekly to help the parents craft their stories into books that could then be given to children and family members in the U.S.

She said the idea came to her about a year ago after listening to a segment on National Public Radio about the children of incarcerated parents.

“I went to the library and could not find a single book explaining deportation to a child,” she said. “The closest book about family separation was about divorce or having to move, but that’s not exactly it. This showed me that there is a need. So many kids are growing up so confused and so affected by this.”

::

But even though, for the little elf, his life seemed normal, he knew his family was not like others. His friends had a dad and a mom and he didn’t. His brothers tried to help him with his confusion. They said, “We think it’s normal, but we know it’s not a normal life,” and they were right — it wasn’t normal to grow up without a mother.

::

What do I tell them? How do I explain to them that you are a deported mother? They are going to think you are a bad person, and you’re not a bad person.

— Ryan Paulsen, 12

Sanchez Paulsen was so certain that the June 6, 2006, visa appointment at the U.S. Consulate in Ciudad Juarez would go her way that she’d already told the boys they’d celebrate the next day at Disneyland.

Instead, immigration officials denied her reentry into the U.S. and banned her from the U.S. for 10 years, the usual punishment for entering the country illegally.

It didn’t matter that her husband, Michael Paulsen, was a U.S. citizen and military veteran, or that Sanchez Paulsen had lived in the U.S. for more than five years, or that the couple had three children together.

Generally, people who are in the country illegally but are married to U.S. citizens are allowed under immigration law to become legal residents. But at the time, there was a snag in immigration law that required applicants to return to their countries of origin as a condition of receiving legal status.

However, once the applicant left the country, the law automatically barred them from returning to the U.S. for at least three years and sometimes up to a decade, even though they were eligible for legal U.S. residency.

When Sanchez Paulsen was barred from returning to the U.S., the plan was to have the boys stay with her in Mexico. But it proved too difficult to raise children in a country where she believed neither the schools nor the standard of living were up to par with the U.S., she said.

At one point, she was so afraid of living in Tijuana that she and the boys would spend the night crammed into the bedroom closet.

“I’d heard so much about this city. How horrible it was. The crime. The violence,” she said. “I lived in fear.”

She’s no longer terrified of the city, spending most of her days taking care of her nephew, writing and knitting hats she can sell to neighbors. And working on finishing “The Little Elf.”

She said it gives her a chance to explain a situation she found hard to clarify for her children, using symbolism, metaphor and imagery to tell a story of banishment.

Going through snapshots of her family, Emma Sanchez Paulsen wipes her eyes. She says she often thinks about the milestones she’s missed in her boys’ lives: their first days of school, graduations, award presentations.

The boys are now older — Alex is 14; Ryan, 12; and Brannon, 9 — and it’s become more complicated.

Recently, Ryan told his mother that he’d had enough.

“It makes me really angry when they ask me where my mom is,” he told his mother about the questions his schoolmates tend to ask.

“I don’t know what to tell them. What do I tell them? How do I explain to them that you are a deported mother? They are going to think you are a bad person, and you’re not a bad person.”

::

The city where mother firefly was locked into smelled of salt, loneliness and a lot of love from the parents separated from their children. The atmosphere was gloomy and sad, and even though she felt much anguish, she also had a lot of faith that one day they would be together again in the happiest city in the world where they were once very happy.

::

Yolanda Varona, a former fast-food restaurant manager in San Diego who now heads a group of mothers living in exile in Tijuana, was deported nearly five years ago after living in the country without legal status for nearly 16 years.

Varona, who first entered the U.S. with a tourist visa, wrote a bedtime story for her adult children and young grandchildren about a firefly mother who struggles to get back to her children — represented by two bright stars — after she is sent to “The Saddest City in the World.”

Her story is mostly about pain and loss.

“Everyone was very happy until one day an enormous black stain arrived at the house. It wanted to separate them,” Varona read in Spanish from her bedtime story. “The stain swallowed her. There wasn’t time to say goodbye. There wasn’t even time for a last kiss or hug.”

Varona said her deportation devastated her family, especially her adult daughter, who ended up losing custody of her own child after she became homeless in the wake of her mother’s deportation.

The book is dedicated to her children and grandchildren. She hopes the story will help them understand her situation.

“I think this will help my daughter understand that I’m suffering and still fighting for her,” Varona said.

Sobko said the group has crowdsourced $2,000, enough money to make books for 10 parents, but she hopes to expand the project into audio and to have some of the books placed in libraries throughout the country.

She said the recurring theme in all of the stories is love and the need for the deported parents to make sure their children know that the separation isn’t their choice.

“They have a tremendous amount of guilt and burden,” she said. “They have this feeling that they are responsible for doing this to their kids and that their kids are suffering and maybe feeling unloved. The stories are powerful because they are real but in an imagined way.”

::

Emma Sanchez Paulsen works on illustrations for “The Little Elf,” the story she has written for her sons trying to explain deportation. Out her window, she gazes toward the hills of the U.S./Mexico border, where her family is waiting for her.

Sanchez Paulsen, who was still breast-feeding her 2-month-old son when she was deported, said she often thinks about the milestones she’s missed in her boys’ lives: their first days of school, graduations, award presentations.

They visit her about twice a month in Tijuana, and they still converge on her bed for a bedtime story when they spend the night.

On the nights she’s alone without a bedtime story to tell, she stares out her bedroom window toward Otay Mountain. Lights perched atop the border fence break up the darkness. She knows her husband and boys are on the other side.

Twitter: @thecindycarcamo

MORE GREAT READS:

For this drummer, no gig tops Griffith Park

Team of sleuths stalks cancer in L.A. County

A java man’s adventure in Japanese coffee roasting

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.