Why California parents will soon have a new way to think about test scores

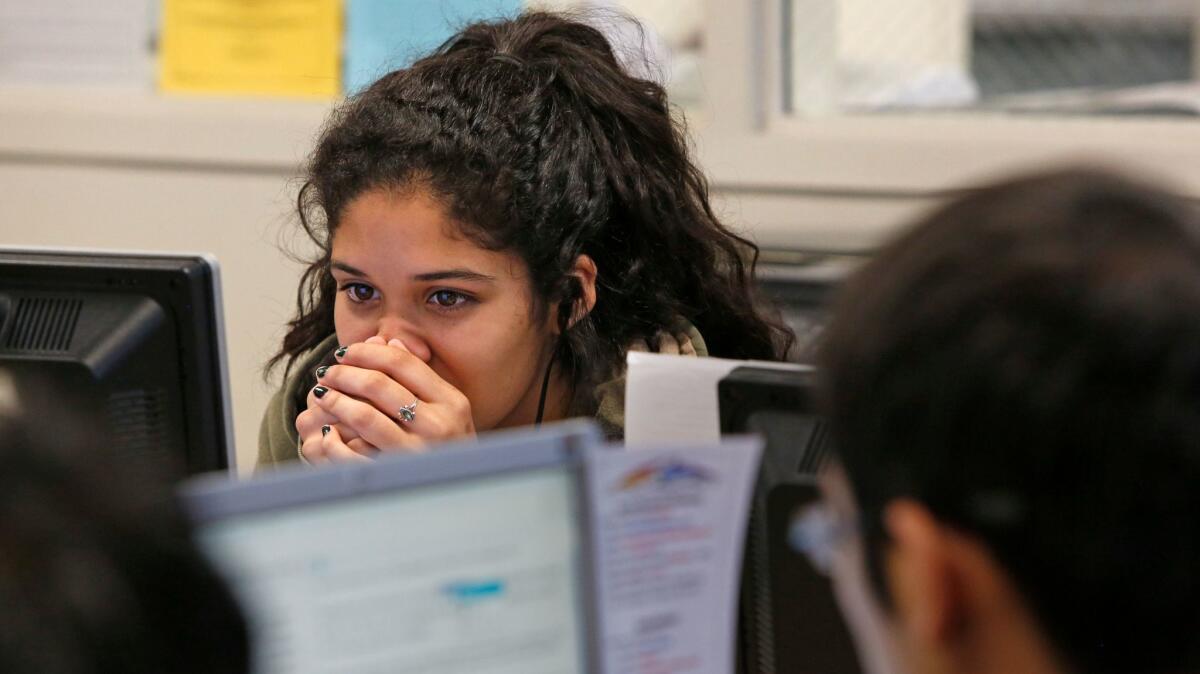

How is your child’s school doing on standardized tests?

Starting this spring, you will be able to get a sense by looking at a number that’s not quite a test score. Instead, you’ll see the difference between the results for the school overall or a single grade at the school versus the state’s definition of proficiency.

The California State Board of Education voted for the new performance measure on Wednesday as part of a shift away from grading schools solely based on raw test scores. The changes are meant to satisfy the reporting requirements of both a recent state school funding law called the Local Control Funding Formula and the federal Every Student Succeeds Act.

Because so many schools perform below the level the state thinks students should be reaching, the new performance numbers will often be negative. Most schools will receive scores between -95 and 45.

Parents will continue to get score reports on their children’s individual progress. The new measure will be part of what the board is calling the “California School Dashboard,” a portal of information the public can use to learn about how schools are doing starting this February or March.

Some advocates at the meeting asked the board to take more time before voting on the proposal.

“Your staff did a great job in a short amount of time, but because of the short amount of time, it feels a bit rushed,” said Brian Rivas, director of policy and government relations at the Education Trust-West, an Oakland-based group that researches and lobbies for educational justice and high academic achievement. “We think this may be the most important part of the whole system.”

Samantha Tran, senior managing director of education policy for Children Now, a group that lobbies and organizes activists on children’s issues, said there are some technical issues that might inflate the scores of elementary schools that serve kindergarten through sixth grade over those that stop at fifth grade.

She also said that the largely negative scores would present a “communications problem.”

Board member Sue Burr said it was “refreshing” to hear stakeholders asking the board to slow down for once. But, she added, “we have to kind of jump off the ledge here, and say, yes, we’re going to go with this system.”

Despite the vote, some still hope for tinkering. Doug McRae, a retired standardized testing specialist, thinks the method is sound but suggested standardizing the scores on a scale of 0-100 percent for consistency — and to make them easier for parents to understand.

Board members seemed open to revision: “This is not the last time we will be discussing the issue,” said President Mike Kirst.

Teachers, advocates and administrators spoke up on another issue: how the state reports the test scores of students who are learning the English language. It might seem like a technicality, but it has real-world consequences, they said.

For the purpose of rating schools, the state plans to combine the scores of students who are currently learning English with those of English learners who have been reclassified as fluent. It’s hard to measure the performance of non-native English speakers, who move in and out of English learner status, officials say — and combining the scores of the different groups would provide more stable results.

Karen Valdes, assistant superintendent at Menifee Union School District, was one of those who spoke up, saying, “I remain concerned about concealing EL [English learner] performance.”

The board voted to keep the combined score, but also committed to reporting scores for the different groups separately, too, so that more information is available.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.