First & Spring: L.A. City Council’s eye for efficiency can anger some Angelenos

Outraged chants erupted at the Los Angeles City Council last month after dozens of people who had come to the meeting discovered they wouldn’t get a chance to speak.

They filled out cards asking to address the council on Item No. 21 — a proposed ban on growing genetically modified organisms in the city. But roughly an hour and a half into the meeting, when the matter finally came up, a clerk announced it was still in committee — and council members briskly moved to the next item.

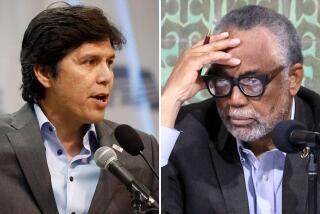

When “we realized we were not able to talk, it got a little radical,” said Cafe Gratitude co-owner Ryland Engelhart, a ban supporter. Loud choruses of “No GMOs!” filled the cavernous council chambers. Council President Herb Wesson tried in vain to quiet the crowd before adjourning the meeting.

The proposed GMO ban had been put on the meeting agenda days earlier, with backers expecting it to sail through a committee and be ready for approval by the full council. But in a move that surprised lawmakers backing the ban, committee members held up the matter indefinitely. Rob Wilcox, spokesman for City Atty. Mike Feuer, said that because of the committee decision, the council couldn’t take up the matter or hear public comment on the topic.

Lawmakers said the events that led to the uproar were unusual. But it wasn’t the first time Angelenos have crowded into council chambers, only to be shut out of the conversation.

It also can happen more routinely — the result of a City Hall practice meant to keep meetings efficient, but sometimes little understood by those wanting to address the council. The full council can turn down requests to speak on an issue if a smaller group of lawmakers have taken public comment in committee.

When Los Angeles lawmakers decided in 2013 to draft rules that would ban the use of bullhooks on circus elephants, scores of people signed up to speak at a council meeting, including a number of opponents from labor unions and a circus production company. The council watched a video of elephants in apparent distress, provided by an animal rights group, but did not hear from the public.

Wesson told the crowd that the city had already provided members of the public a chance to comment in committee — a fact that was noted on the meeting agenda. But some opponents of the bullhook ban were upset that they couldn’t make their case before the whole council.

“In terms of the fairness of the process, that’s laughable,” Stephen Payne, vice president of corporate communications for Feld Entertainment, the parent company of Ringling Bros., later said in an interview.

City officials say the practice is legal under state law.

Jim Ewert, general counsel for the California Newspaper Publishers Assn., agreed. Government agencies can restrict comment to a committee as long as the committee is made up exclusively of council members, the public has had a chance to address them and the proposal has not changed substantially before the full council takes its vote, he said.

Like City Council meetings, committee meetings in L.A. are announced in advance via online and printed agendas, are held at City Hall and are open to the public. “We have a system in place that works,” Wesson said. “We make sure that people are afforded the opportunity to state their case in committee.”

The smaller, more specialized committees pore over the details of proposed laws. Councilman Paul Koretz pointed out that the average Angeleno has a much better chance to shape a proposal if they show up at the committee rather than the council meetings, since “that’s where the action is 99% of the time.”

But critics say the practice limits chances to weigh in on City Hall decisions.

“It’s lawful,” said Terry Francke, general counsel for Californians Aware, a nonprofit that promotes open government. “But it does cheat the public of a realistic opportunity to participate.... It serves the need and convenience of the government much more than the citizens.”

Lobbyists or community groups sometimes drum up big crowds for committee meetings, but they usually draw fewer people than full council meetings. The Times and other news outlets sometimes don’t report on new proposals until they have passed through committee.

“Insiders probably aren’t bothered too much,” Francke said. “But for the average person, the first time they hear about something, it may be too late to address the government about it.”

The City Hall system is similar to that of the California Legislature, where public comment is taken during committee meetings but not when legislation reaches the Assembly or Senate floor. Nearly half of L.A.’s council members have served in the Legislature, including Council President Wesson, who runs council meetings with a Sacramento style.

Wesson “attempts to have more streamlined council meetings,” said Koretz, who championed the GMO ban. “Generally, I think it works well. Once in a great while it doesn’t.”

The full council can opt to hear more from audience members, even when it has taken public comment in committee. During a September council meeting, people lined up to weigh in on a proposed minimum-wage increase for hotel workers, after a committee heard from dozens of people the day before. Wesson said he weighs “a variety of factors” when deciding whether to reopen public comment, including requests from council members and the length of the meeting agenda.

Members of the public can always sign up to speak at the end of the meeting, during a time set aside for audience members to raise issues not on the agenda. That was how one — and only one — person got a chance to address the council about GMOs last month. But speaking to lawmakers then — possibly after they have considered an issue — holds little appeal for some Angelenos.

Lori Bennett, a GMO opponent, said she “was upset that we couldn’t say anything at all” during the December meeting. The full council missed out on something, she said. “They would have heard our passion.”

[email protected]

Twitter: @LATimesEmily

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.